Genre Other. Page - 355

ring accidents, was an adventure for volunteers.

The population of the United States was stabilized at forty-million souls.

One bright morning in the Chicago Lying-in Hospital, a man named Edward K. Wehling, Jr., waited for his wife to give birth. He was the only man waiting. Not many people were born a day any more.

Wehling was fifty-six, a mere stripling in a population whose average age was one hundred and twenty-nine.

X-rays had revealed that his wife was going to have triplets. The children would be his first.

Young Wehling was hunched in his chair, his head in his hand. He was so rumpled, so still and colorless as to be virtually invisible. His camouflage was perfect, since the waiting room had a disorderly and demoralized air, too. Chairs and ashtrays had been moved away from the walls. The floor was paved with spattered dropcloths.

The room was being redecorated. It was being redecorated as a memorial to a man who had voluntee

successive Gaol Lane and King Street of other periods - he would look upward to the east and see the arched flight of steps to which the highway had to resort in climbing the slope, and downward to the west, glimpsing the old brick colonial schoolhouse that smiles across the road at the ancient Sign of Shakespeare's Head where the Providence Gazette and Country-Journal was printed before the Revolution. Then came the exquisite First Baptist Church of 1775, luxurious with its matchless Gibbs steeple, and the Georgian roofs and cupolas hovering by. Here and to the southward the neighbourhood became better, flowering at last into a marvellous group of early mansions; but still the little ancient lanes led off down the precipice to the west, spectral in their many-gabled archaism and dipping to a riot of iridescent decay where the wicked old water-front recalls its proud East India days amidst polyglot vice and squalor, rotting wharves, and blear-eyed ship-chandleries, with such surviving alley names as Packet, B

ecrets.

After all, Theseus damn well was.

*

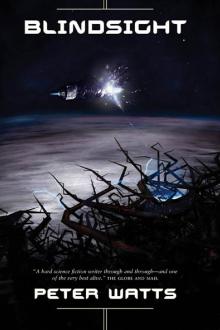

She'd taken us a good fifteen AUs towards our destination before something scared her off course. Then she'd skidded north like a startled cat and started climbing: a wild high three-gee burn off the ecliptic, thirteen hundred tonnes of momentum bucking against Newton's First. She'd emptied her Penn tanks, bled dry her substrate mass, squandered a hundred forty days' of fuel in hours. Then a long cold coast through the abyss, years of stingy accounting, the thrust of every antiproton weighed against the drag of sieving it from the void. Teleportation isn't magic: the Icarus stream couldn't send us the actual antimatter it made, only the quantum specs. Theseus had to filterfeed the raw material from space, one ion at a time. For long dark years she'd made do on pure inertia, hording every swallowed atom. Then a flip; ionizing lasers strafing the space ahead; a ramscoop thrown wide in a hard brake. The weight of a trillion trilli

r guided by the example of Christ in the treatment of enemies; therefore they cannot be agreeable to the will of God, and therefore their overthrow by a spiritual regeneration of their subjects is inevitable.

"We regard as unchristian and unlawful not only all wars, whether offensive or defensive, but all preparations for war; every naval ship, every arsenal, every fortification, we regard as unchristian and unlawful; the existence of any kind of standing army, all military chieftains, all monuments commemorative of victory over a fallen foe, all trophies won in battle, all celebrations in honor of military exploits, all appropriations for defense by arms; we regard as unchristian and unlawful every edict of government requiring of its subjects military service.

"Hence we deem it unlawful to bear arms, and we cannot hold any office which imposes on its incumbent the obligation to compel men to do right on pain of imprisonment or death. We therefore voluntarily exclude ourselves from every legisl

Joy's eyes were upon mine.

"Darling! I didn't have the least idea. Why, it's going to be wonderful! Never a dull moment!"

I kissed my bride, after which she said, "I think I could do with a drink, sweetheart."

"Your wish is my command."

I got up and started toward the liquor supply inside the house. Joy's soft call stopped me.

"What is it, angel?" I inquired.

"Not just a drink, sweet. Bring the bottle."

I went into the kitchen and got a bottle of brandy. But upon returning, I discovered I'd neglected to bring glasses.

But Joy took the bottle from me in a rather dazed manner, knocked off the neck against a leg of the bench and tipped the bottle to her beautiful lips. She took a pull of brandy large enough to ward off the worst case of pneumonia and then passed the bottle to Bag Ears.

"Drink hearty, pal," she murmured, and sort of sank down into herself.

I never got my turn at the bott

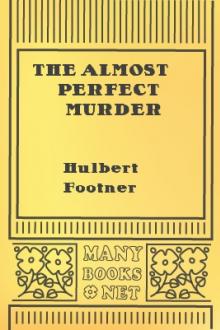

was immediately carried into the house and laid upon the bed. The family physician was telephoned for. The powder marks around the wound could be seen by all. In his confusion and excitement, the butler felt that he ought to notify his master of what had happened before sending for the police. Nobody in the house knew where Mr. Whittall was dining that night, and the butler started telephoning around to his clubs, and to the houses of his most intimate friends in the endeavour to find him. He could not get any word of him. He was still at the telephone when Mr. Whittall returned home. This would be about eleven. Mr. Whittall's first act was to telephone to the local police station. He upbraided the butler for not having done so at once. A few minutes later the police were in the house.

Mrs. Whittall's own maid had identified the revolver as one belonging to her mistress. She had testified that she had seen nothing strange in the behaviour of her mistress before she left the house. So far as she could

ury of both.

When the French Revolution broke out, it certainly afforded to Mr. Burke an opportunity of doing some good, had he been disposed to it; instead of which, no sooner did he see the old prejudices wearing away, than he immediately began sowing the seeds of a new inveteracy, as if he were afraid that England and France would cease to be enemies. That there are men in all countries who get their living by war, and by keeping up the quarrels of Nations, is as shocking as it is true; but when those who are concerned in the government of a country, make it their study to sow discord and cultivate prejudices between Nations, it becomes the more unpardonable.

With respect to a paragraph in this work alluding to Mr. Burke's having a pension, the report has been some time in circulation, at least two months; and as a person is often the last to hear what concerns him the most to know, I have mentioned it, that Mr. Burke may have an opportunity of contradicting the rumour, if he thinks proper.

ion, and perhaps enabled him to popularize his subject, but for his Satanic contempt for all academic dignitaries and persons in general who thought more of Greek than of phonetics. Once, in the days when the Imperial Institute rose in South Kensington, and Joseph Chamberlain was booming the Empire, I induced the editor of a leading monthly review to commission an article from Sweet on the imperial importance of his subject. When it arrived, it contained nothing but a savagely derisive attack on a professor of language and literature whose chair Sweet regarded as proper to a phonetic expert only. The article, being libelous, had to be returned as impossible; and I had to renounce my dream of dragging its author into the limelight. When I met him afterwards, for the first time for many years, I found to my astonishment that he, who had been a quite tolerably presentable young man, had actually managed by sheer scorn to alter his personal appearance until he had become a sort of walking repudiation of Oxford an

e matron.

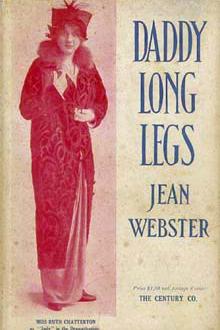

`This gentleman has taken an interest in several of our boys. You remember Charles Benton and Henry Freize? They were both sent through college by Mr.--er--this Trustee, and both have repaid with hard work and success the money that was so generously expended. Other payment the gentleman does not wish. Heretofore his philanthropies have been directed solely towards the boys; I have never been able to interest him in the slightest degree in any of the girls in the institution, no matter how deserving. He does not, I may tell you, care for girls.'

`No, ma'am,' Jerusha murmured, since some reply seemed to be expected at this point.

`To-day at the regular meeting, the question of your future was brought up.'

Mrs. Lippett allowed a moment of silence to fall, then resumed in a slow, placid manner extremely trying to her hearer's suddenly tightened nerves.

`Usually, as you know, the children are not kept after they are sixteen, but an exception was made in your case. You

THIS book is a slice of intensified historyhistory as I saw it. It does not pretend to be anything but a detailed account of the November Revolution, when the Bolsheviki, at the head of the workers and soldiers, seized the state power of Russia and placed it in the hands of the Soviets.

Naturally most of it deals with Red Petrograd, the capital and heart of the insurrection. But the reader must realize that what took place in Petrograd was almost exactly duplicated, with greater or lesser intensity, at different intervals of time, all over Russia.

In this book, the first of several which I am writing, I must confine myself to a chronicle of those events which I myself observed and experienced, and those supported by reliable evidence; preceded by two chapters briefly outlining the background and causes of the November Revolution. I am aware that these two chapters make difficult reading, but they are essential to an understanding of what follows.

Many questions will suggest themselves to the mind of the reader. What is Bolshevism? What kind of