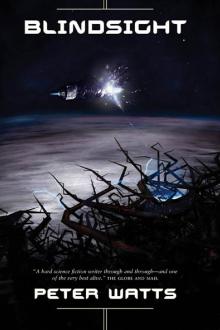

Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖

- Author: Peter Watts

- Performer: 0765312182

Book online «Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖». Author Peter Watts

I was installing the Faraday bell. Trying to. It should have been simple enough; I’d already run the main anchor line down from the vestibule to the flaccid sack floating in the middle of the passageway. I was—that’s right, something about a spring line. To, to keep the bell centered. The wall glistened in my headlamp like wet clay. Satanic runes sparkled in my imagination.

I jammed the spring line’s pad against the wall. I could have sworn the substrate flinched. I fired my thrust pistol, retreated back to the center of the passage.

“They’re here,” James whispered.

Something was. I could feel it always behind me, no matter where I turned. I could feel some great roaring darkness swirling just out of sight, a ravenous mouth as wide as the tunnel itself. Any moment now it would lunge forward at impossible speed and engulf us all.

“They’re beautiful…” James said. There was no fear in her voice at all. She sounded awestruck.

“What? Where?” Bates never stopped turning, kept trying to keep the whole three-sixty in sight at once. The drones under her command wobbled restlessly to either side, armored parentheses pointing down the passageway in opposite directions. “What do you see?”

“Not out there. In here. Everywhere. Can’t you see it?”

“I can’t see anything,” Szpindel said, his voice shaking.

“It’s in the EM fields,” James said. “That’s how they communicate. The whole structure is full of language, it’s—”

“I can’t see anything,” Szpindel repeated. His breath echoed loud and fast over the link. “I’m blind.”

“Shit.” Bates swung on Szpindel. “How can that—the radiation—”

“I d-don’t think that’s it..”

Nine Tesla, and the ghosts were everywhere. I smelled asphalt and honeysuckle.

“Keeton!” Bates called. “You with us?”

“Y-yeah.” Barely. I was back at the bell, my hand on the ripcord. Trying to ignore whatever kept tapping me on the shoulder.

“Leave that! Get him outside!”

“No!” Szpindel floated helplessly in the passage, his pistol bouncing against its wrist tether. “No, throw me something.”

“What?”

It’s all in your head. It’s all in your—

“Throw something! Anything!”

Bates hesitated. “You said you were bli—”

“Just do it!”

Bates pulled a spare suit battery off her belt and lobbed it. Szpindel reached, fumbled. The battery slipped from his grasp and bounced off the wall.

“I’ll be okay,” he gasped. “Just get me into the tent.”

I yanked the cord. The bell inflated like a great gunmetal marshmallow.

“Everyone inside!” Bates ran her pistol with one hand, grabbed Szpindel with the other. She handed him off to me and slapped a sensor pod onto the skin of the tent. I pulled back the shielded entrance flap as though pulling a scab from a wound. The single molecule beneath, infinitely long, endlessly folded against itself, swirled and glistened like a soap bubble.

“Get him in. James! Get down here!”

I pushed Szpindel through the membrane. It split around him with airtight intimacy, hugged each tiny crack and contour as he passed through.

“James! Are you—”

“Get it off me!” Harsh voice, raw and scared and scary, as male as female could sound. Cruncher in control. “Get it off!”

I looked back. Susan James’ body tumbled slowly in the tunnel, grasping its right leg with both hands.

“James!” Bates sailed over to the other woman. “Keeton! Help out!” She took the Gang by the arm. “Cruncher? What’s the problem?”

“That! You blind?” He wasn’t just grasping at the limb, I realized as I joined them. He was tugging at it. He was trying to pull it off.

Something laughed hysterically, right inside my helmet.

“Take his arm,” Bates told me, taking his right one, trying to pry the fingers from their death grip on the Gang’s leg. “Cruncher, let go. Now.”

“Get it off me!”

“It’s your leg, Cruncher.” We wrestled our way towards the diving bell.

“It’s not my leg! Just look at it, how could it—it’s dead. It’s stuck to me…”

Almost there. “Cruncher, listen,” Bates snapped. “Are you with m—”

“Get it off!”

We stuffed the Gang into the tent. Bates moved aside as I dove in after them. Amazing, the way she held it together. Somehow she kept the demons at bay, herded us to shelter like a border collie in a thunderstorm. She was—

She wasn’t following us in. She wasn’t even there. I turned to see her body floating outside the tent, one gloved hand grasping the edge of the flap; but even under all those layers of Kapton and Chromel and polycarbonate, even behind the distorted half-reflections on her faceplate, I could tell that something was missing. All her surfaces had just disappeared.

This couldn’t be Amanda Bates. The thing before me had no more topology than a mannequin.

“Amanda?” The Gang gibbered at my back, softly hysteric.

Szpindel: “What’s happening?”

“I’ll stay out here,” Bates said. She had no affect whatsoever. “I’m dead anyway.”

“Wha—” Szpindel had lots. “You will be, if you don’t—”

“You leave me here,” Bates said. “That’s an order.”

She sealed us in.

*

It wasn’t the first time, not for me. I’d had invisible fingers poking through my brain before, stirring up the muck, ripping open the scabs. It was far more intense when Rorschach did it to me, but Chelsea was more—

—precise, I guess you’d say.

Macramé, she called it: glial jumpstarts, cascade effects, the splice and dice of critical ganglia. While I trafficked in the reading of Human architecture, Chelsea changed it—finding the critical nodes and nudging them just so, dropping a pebble into some trickle at the headwaters of memory and watching the ripples build to a great rolling cascade deep in the downstream psyche. She could hotwire happiness in the time it took to fix a sandwich, reconcile you with your whole childhood in the course of a lunch hour or three.

Like so many other domains of human invention, this one had learned to run without her. Human nature was becoming an assembly-line edit, Humanity itself increasingly relegated from Production to product. Still. For me, Chelsea’s skill set recast a strange old world in an entirely new light: the cut-and-paste of minds not for the greater good of some abstract society, but for the simple selfish wants of the individual.

“Let me give you the gift of happiness,” she said.

“I’m already pretty happy.”

“I’ll make you happier. A TAT, on me.”

“Tat?”

“Transient Attitudinal Tweak. I’ve still got privileges at Sax.”

“I’ve been tweaked plenty. Change one more synapse and I might turn into someone else.”

“That’s ridiculous and you know it. Or every experience you had would turn you into a different person.”

I thought about that. “Maybe it does.”

But she wouldn’t let it go, and even the strongest anti-happiness argument was bound to be an uphill proposition; so one afternoon Chelsea fished around in her cupboards and dredged up a hairnet studded with greasy gray washers. The net was a superconducting spiderweb, fine as mist, that mapped the fields of merest thought. The washers were ceramic magnets that bathed the brain in fields of their own. Chelsea’s inlays linked to a base station that played with the interference patterns between the two.

“They used to need a machine the size of a bathroom just to house the magnets.” She laid me back on the couch and stretched the mesh across my skull. “That’s the only outright miracle you get with a portable setup like this. We can find hot spots, and we can even zap ‘em if they need zapping, but TMS effects fade after a while. We’ll have to go to a clinic for anything permanent.”

“So we’re fishing for what, exactly? Repressed memories?”

“No such thing.” She grinned in toothy reassurance. “There are only memories we choose to ignore, or kinda think around, if you know what I mean.”

“I thought this was the gift of happiness. Why—”

She laid a fingertip across my lips. “Believe it or not, Cyggers, people sometimes choose to ignore even good memories. Like, say, if they enjoyed something they didn’t think they should. Or—” she kissed my forehead— “if they don’t think they deserve to be happy.”

“So we’re going for—”

“Potluck. You can never tell ‘til you get a bite. Close your eyes.”

A soft hum started up somewhere between my ears. Chelsea’s voice led me on through the darkness. “Now keep in mind, memories aren’t historical archives. They’re—improvisations, really. A lot of the stuff you associate with a particular event might be factually wrong, no matter how clearly you remember it. The brain has a funny habit of building composites. Inserting details after the fact. But that’s not to say your memories aren’t true, okay? They’re an honest reflection of how you saw the world, and every one of them went into shaping how you see it. But they’re not photographs. More like impressionist paintings. Okay?”

“Okay.”

“Ah,” she said. “There’s something.”

“What?”

“Functional cluster. Getting a lot of low-level use but not enough to intrude into conscious awareness. Let’s just see what happens when we—”

And I was ten years old, and I was home early and I’d just let myself into the kitchen and the smell of burned butter and garlic hung in the air. Dad and Helen were fighting in the next room. The flip-top on our kitchen-catcher had been left up, which was sometimes enough to get Helen going all by itself. But they were fighting about something else; Helen only wanted what was best for all of us but Dad said there were limits and this was not the way to go about it. And Helen said _you don’t know what it’s like you hardly ever even see him_ and then I knew they were fighting about me. Which in and of itself was nothing unusual.

What really scared me was that for the first time ever, Dad was fighting back.

“You do not force something like that onto someone. Especially without their knowledge.” My father never shouted—his voice was as low and level as ever—but it was colder than I’d ever heard, and hard as iron.

“That’s just garbage,” Helen said. “Parents always make decisions for their children, in their best interests, especially when it comes to medical iss—”

“This is not a medical issue.” This time my father’s voice did rise. “It’s—”

“Not a medical issue! That’s a new height of denial even for you! They cut out half his brain in case you missed it! Do you think he can recover from that without help? Is that more of your father’s tough love shining through? Why not just deny him food and water while you’re at it!”

“If mu-ops were called for they’d have been prescribed.”

I felt my face scrunching at the unfamiliar word. Something small and white beckoned from the open garbage pail.

“Jim, be reasonable. He’s so distant, he barely even talks to me.”

“They said it would take time.”

“But two years! There’s nothing wrong with helping nature along a little, we’re not even talking black market. It’s over-the-counter, for God’s sake!”

“That’s not the point.”

An empty pill bottle. That’s what one of them had thrown out, before forgetting to close the lid. I salvaged it from the kitchen discards and sounded out the label in my head.

“Maybe the point should be that someone who’s barely home three months of the year has got his bloody nerve passing judgment on my parenting skills. If you want a say in how he’s raised, then you

Comments (0)