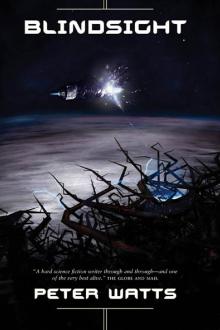

Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖

- Author: Peter Watts

- Performer: 0765312182

Book online «Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖». Author Peter Watts

If he’d been Human I’d have known instantly what I saw there, I’d have smelled murderer all over his topology. And I wouldn’t have been able to even guess at the number of his victims, because his affect was so utterly without remorse. The killing of a hundred would leave no more stain on Sarasti’s surfaces than the swatting of an insect; guilt beaded and rolled off this creature like water on wax.

But Sarasti wasn’t human. Sarasti was a whole different animal, and coming from him all those homicidal refractions meant nothing more than predator. He had the inclination, was born to it; whether he had ever acted on it was between him and Mission Control.

Maybe they cut you some slack, I didn’t say to him. Maybe it’s just a cost of doing business. You’re mission-critical, after all. For all I know you cut a deal. You’re so very smart, you know we wouldn’t have brought you back in the first place if we hadn’t needed_ you. From the day they cracked the vat you knew you had leverage._

Is that how it works, Jukka? You save the world, and the folks who hold your leash agree to look the other way?

As a child I’d read tales about jungle predators transfixing their prey with a stare. Only after I’d met Jukka Sarasti did I know how it felt. But he wasn’t looking at me now. He was focused on installing his own tent, and even if he had looked me in the eye there’d have been nothing to see but the dark wraparound visor he wore in deference to Human skittishness. He ignored me as I grabbed a nearby rung and squeezed past.

I could have sworn I smelled raw meat on his breath.

Into the drum (_drums_, technically; the BioMed hoop at the back spun on its own bearings). I flew through the center of a cylinder sixteen meters across. Theseus‘ spinal nerves ran along its axis, the exposed plexii and piping bundled against the ladders on either side. Past them, Szpindel’s and James’ freshly-erected tents rose from nooks on opposite sides of the world. Szpindel himself floated off my shoulder, still naked but for his gloves, and I could tell from the way his fingers moved that his favorite color was green. He anchored himself to one of three stairways to nowhere arrayed around the drum: steep narrow steps rising five vertical meters from the deck into empty air.

The next hatch gaped dead-center of the drum’s forward wall; pipes and conduits plunged into the bulkhead to each side. I grabbed a convenient rung to slow myself—biting down once more on the pain—and floated through.

T-junction. The spinal corridor continued forward, a smaller diverticulum branched off to an EVA cubby and the forward airlock. I stayed the course and found myself back in the crypt, mirror-bright and less than two meters deep. Empty pods gaped to the left; sealed ones huddled to the right. We were so irreplaceable we’d come with replacements. They slept on, oblivious. I’d met three of them back in training. Hopefully none of us would be getting reacquainted any time soon.

Only four pods to starboard, though. No backup for Sarasti.

Another hatchway. Smaller this time. I squeezed through into the bridge. Dim light there, a silent shifting mosaic of icons and alphanumerics iterating across dark glassy surfaces. Not so much bridge as cockpit, and a cramped one at that. I’d emerged between two acceleration couches, each surrounded by a horseshoe array of controls and readouts. Nobody expected to ever use this compartment. Theseus was perfectly capable of running herself, and if she wasn’t we were capable of running her from our inlays, and if we weren’t the odds were overwhelming that we were all dead anyway. Still, against that astronomically off-the-wall chance, this was where one or two intrepid survivors could pilot the ship home again after everything else had failed.

Between the footwells the engineers had crammed one last hatch and one last passageway: to the observation blister on Theseus‘ prow. I hunched my shoulders (tendons cracked and complained) and pushed through—

—into darkness. Clamshell shielding covered the outside of the dome like a pair of eyelids squeezed tight. A single icon glowed softly from a touchpad to my left; faint stray light followed me through from the spine, brushed dim fingers across the concave enclosure. The dome resolved in faint shades of blue and gray as my eyes adjusted. A stale draft stirred the webbing floating from the rear bulkhead, mixed oil and machinery at the back of my throat. Buckles clicked faintly in the breeze like impoverished wind chimes.

I reached out and touched the crystal: the innermost layer of two, warm air piped through the gap between to cut the cold. Not completely, though. My fingertips chilled instantly.

Space out there.

Perhaps, en route to our original destination, Theseus had seen something that scared her clear out of the solar system. More likely she hadn’t been running away from anything but to something else, something that hadn’t been discovered until we’d already died and gone from Heaven. In which case…

I reached back and tapped the touchpad. I half-expected nothing to happen; Theseus’ windows could be as easily locked as her comm logs. But the dome split instantly before me, a crack then a crescent then a wide-eyed lidless stare as the shielding slid smoothly back into the hull. My fingers clenched reflexively into a fistful of webbing. The sudden void stretched empty and unforgiving in all directions, and there was nothing to cling to but a metal disk barely four meters across.

Stars, everywhere. So many stars that I could not for the life me understand how the sky could contain them all yet be so black. Stars, and—

—nothing else.

What did you expect? I chided myself. An alien mothership hanging off the starboard bow?

Well, why not? We were out here for something.

The others were, anyway. They’d be essential no matter where we’d ended up. But my own situation was a bit different, I realized. My usefulness degraded with distance.

And we were over half a light year from home.

“When it is dark enough, you can see the stars.”

—Emerson

Where was I when the lights came down?

I was emerging from the gates of Heaven, mourning a father who was—to his own mind, at least—still alive.

It had been scarcely two months since Helen had disappeared under the cowl. Two months by our reckoning, at least. From her perspective it could have been a day or a decade; the Virtually Omnipotent set their subjective clocks along with everything else.

She wasn’t coming back. She would only deign to see her husband under conditions that amounted to a slap in the face. He didn’t complain. He visited as often as she would allow: twice a week, then once. Then every two. Their marriage decayed with the exponential determinism of a radioactive isotope and still he sought her out, and accepted her conditions.

On the day the lights came down, I had joined him at my mother’s side. It was a special occasion, the last time we would ever see her in the flesh. For two months her body had lain in state along with five hundred other new ascendants on the ward, open for viewing by the next of kin. The interface was no more real than it would ever be, of course; the body could not talk to us. But at least it was there, its flesh warm, the sheets clean and straight. Helen’s lower face was still visible below the cowl, though eyes and ears were helmeted. We could touch her. My father often did. Perhaps some distant part of her still felt it.

But eventually someone has to close the casket and dispose of the remains. Room must be made for the new arrivals—and so we came to this last day at my mother’s side. Jim took her hand one more time. She would still be available in her world, on her terms, but later this day the body would be packed into storage facilities crowded far too efficiently for flesh and blood visitors. We had been assured that the body would remain intact—the muscles electrically exercised, the body flexed and fed, the corpus kept ready to return to active duty should Heaven experience some inconceivable and catastrophic meltdown. Everything was reversible, we were told. And yet—there were so many who had ascended, and not even the deepest catacombs go on forever. There were rumors of dismemberment, of nonessential body parts hewn away over time according to some optimum-packing algorithm. Perhaps Helen would be a torso this time next year, a disembodied head the year after. Perhaps her chassis would be stripped down to the brain before we’d even left the building, awaiting only that final technological breakthrough that would herald the arrival of the Great Digital Upload.

Rumors, as I say. I personally didn’t know of anyone who’d come back after ascending, but then why would anyone want to? Not even Lucifer left Heaven until he was pushed.

Dad might have known for sure—Dad knew more than most people, about the things most people weren’t supposed to know—but he never told tales out of turn. Whatever he knew, he’d obviously decided its disclosure wouldn’t have changed Helen’s mind. That would have been enough for him.

We donned the hoods that served as day passes for the Unwired, and we met my mother in the spartan visiting room she imagined for these visits. She’d built no windows into the world she occupied, no hint of whatever utopian environment she’d constructed for herself. She hadn’t even opted for one of the prefab visiting environments designed to minimize dissonance among visitors. We found ourselves in a featureless beige sphere five meters across. There was nothing in there but her.

Maybe not so far removed from her vision of utopia after all, I thought.

My father smiled. “Helen.”

“Jim.” She was twenty years younger than the thing on the bed, and still she made my skin crawl. “Siri! You came!”

She always used my name. I don’t think she ever called me son.

“You’re still happy here?” my father asked.

“Wonderful. I do wish you could join us.”

Jim smiled. “Someone has to keep the lights on.”

“Now you know this isn’t goodbye,” she said. “You can visit whenever you like.”

“Only if you do something about the scenery.” Not just a joke, but a lie; Jim would have come at her call even if the gauntlet involved bare feet and broken glass.

“And Chelsea, too,” Helen continued. “It would be so nice to finally meet her after all this time.”

“Chelsea’s gone, Helen,” I said.

“Oh yes but I know you stay in touch. I know she was special to you. Just because you’re not together any more doesn’t mean she can’t—”

“You know she—”

A startling possibility stopped me in midsentence: maybe I hadn’t actually told them.

“Son,” Jim said quietly. “Maybe you could give us a moment.”

I would have given them a fucking lifetime. I unplugged myself back to the ward, looked from the corpse on the bed to my blind and catatonic father in his couch, murmuring sweet nothings into the datastream. Let them perform for each other. Let them formalize and finalize their so-called relationship in whatever way they saw fit. Maybe, just once, they could even bring themselves to be honest, there in that other world where everything else was a lie. Maybe.

I felt no desire to bear witness either way.

But of course I had to go back in for my

Comments (0)