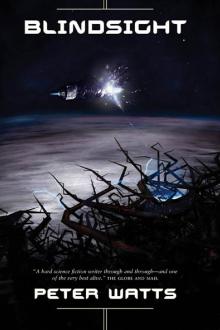

Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖

- Author: Peter Watts

- Performer: 0765312182

Book online «Blindsight by Peter Watts (the unexpected everything TXT) 📖». Author Peter Watts

Yes. Bates. Stepping off the stairway onto the deck

“Grab a chair,” Cunningham said from his seat in the Commons. “It’s golden oldies time.”

There was something about her.

“I’m sick of that song,” Bates said. “We’ve played it to death.”

Even now, my tools chipped and battered, my perceptions barely more than baseline, I could see the change. This torture of prisoners, this assault upon of crew, had crossed a line in her head. The others wouldn’t see it. The lid on her affect was tight as a boilerplate. But even through the dim shadows of my window the topology glowed around her like neon.

Amanda Bates was no longer merely considering a change of command. Now it was only a matter of when.

*

The universe was closed and concentric.

My tiny refuge lay in its center. Outside that shell was another, ruled by a monster, patrolled by his lackeys. Beyond that was another still, containing something even more monstrous and incomprehensible, something that might soon devour us all.

There was nothing else. Earth was a vague hypothesis, irrelevant to this pocket cosmos. I saw no place into which it might fit.

I stayed in the center of the universe for a long time, hiding. I kept the lights off. I didn’t eat. I crept from my tent only to piss or shit in the cramped head down at Fab, and only when the spine was deserted. A field of painful blisters rose across my flash-burned back, as densely packed as kernels on a corncob. The slightest abrasion tore them open.

Nobody tapped at my door, nobody called my name through ConSensus. I wouldn’t have answered if they had. Maybe they knew that, somehow. Maybe they kept their distance out of respect for my privacy and my disgrace.

Maybe they just didn’t give a shit.

I peeked outside now and then, kept an eye on Tactical. I saw Scylla and Charybdis climb into the accretion belt and return towing captured reaction mass in a great distended mesh between them. I watched our ampsat reach its destination in the middle of nowhere, saw antimatter’s quantum blueprints stream down into Theseus‘s buffers. Mass and specs combined in Fab, topped up our reserves, forged the tools that Jukka Sarasti needed for his master plan, whatever that was.

Maybe he’d lose. Maybe Rorschach would kill us all, but not before it had played with Sarasti the way Sarasti had played with me. That would almost make it worthwhile. Or maybe Bates’ mutiny would come first, and succeed. Maybe she would slay the monster, and commandeer the ship, and take us all to safety.

But then I remembered: the universe was closed, and so very small. There was really nowhere else to go.

I put my ear to feeds throughout the ship. I heard routine instructions from the predator, murmured conversations among the prey. I took in only sound, never sight; a video feed would have spilled light into my tent, left me naked and exposed. So I listened in the darkness as the others spoke among themselves. It didn’t happen often any more. Perhaps too much had been said already, perhaps there was nothing left to do but mind the countdown. Sometimes hours would pass with no more than a cough or a grunt.

When they did speak, they never mentioned my name. Only once did I hear any of them even hint at my existence.

That was Cunningham, talking to Sascha about zombies. I heard them in the galley over breakfast, unusually talkative. Sascha hadn’t been let out for a while, and was making up for lost time. Cunningham let her, for reasons of his own. Maybe his fears had been soothed somehow, maybe Sarasti had revealed his master plan. Or maybe Cunningham simply craved distraction from the imminence of the enemy.

“It doesn’t bug you?” Sascha was saying. “Thinking that your mind, the very thing that makes you you, is nothing but some kind of parasite?”

“Forget about minds,” he told her. “Say you’ve got a device designed to monitor—oh, cosmic rays, say. What happens when you turn its sensor around so it’s not pointing at the sky anymore, but at its own guts?” He answered himself before she could: “It does what it’s built to. It measures cosmic rays, even though it’s not looking at them any more. It parses its own circuitry in terms of cosmic-ray metaphors, because those feel right, because they feel natural, because it can’t look at things any other way. But it’s the wrong metaphor. So the system misunderstands everything about itself. Maybe that’s not a grand and glorious evolutionary leap after all. Maybe it’s just a design flaw.”

“But you’re the biologist. You know Mom was right better’n anyone. Brain’s a big glucose hog. Everything it does costs through the nose.”

“True enough,” Cunningham admitted.

“So sentience has gotta be good for something, then. Because it’s expensive, and if it sucks up energy without doing anything useful then evolution’s gonna weed it out just like that.”

“Maybe it did.” He paused long enough to chew food or suck smoke. “Chimpanzees are smarter than Orangutans, did you know that? Higher encephalisation quotient. Yet they can’t always recognize themselves in a mirror. Orangs can.”

“So what’s your point? Smarter animal, less self-awareness? Chimpanzees are becoming nonsentient?”

“Or they were, before we stopped everything in its tracks.”

“So why didn’t that happen to us?”

“What makes you think it didn’t?”

It was such an obviously stupid question that Sascha didn’t have an answer for it. I could imagine her gaping in the silence.

“You’re not thinking this through,” Cunningham said. “We’re not talking about some kind of zombie lurching around with its arms stretched out, spouting mathematical theorems. A smart automaton would blend in. It would observe those around it, mimic their behavior, act just like everyone else. All the while completely unaware of what it was doing. Unaware even of its own existence.”

“Why would it bother? What would motivate it?”

“As long as you pull your hand away from an open flame, who cares whether you do it because it hurts or because some feedback algorithm says withdraw if heat flux exceeds critical T? Natural selection doesn’t care about motives. If impersonating something increases fitness, then nature will select good impersonators over bad ones. Keep it up long enough and no conscious being would be able to pick your zombie out of a crowd.” Another silence; I could hear him chewing through it. “It’ll even be able to participate in a conversation like this one. It could write letters home, impersonate real human feelings, without having the slightest awareness of its own existence.”

“I dunno, Rob. It just seems—”

“Oh, it might not be perfect. It might be a bit redundant, or resort to the occasional expository infodump. But even real people do that, don’t they?”

“And eventually, there aren’t any real people left. Just robots pretending to give a shit.”

“Perhaps. Depends on the population dynamics, among other things. But I’d guess that at least one thing an automaton lacks is empathy; if you can’t feel, you can’t really relate to something that does, even if you act as though you do. Which makes it interesting to note how many sociopaths show up in the world’s upper echelons, hmm? How ruthlessness and bottom-line self-interest are so lauded up in the stratosphere, while anyone showing those traits at ground level gets carted off into detention with the Realists. Almost as if society itself is being reshaped from the inside out.”

“Oh, come on. Society was always pretty— wait, you’re saying the world’s corporate elite are nonsentient?”

“God, no. Not nearly. Maybe they’re just starting down that road. Like chimpanzees.”

“Yeah, but sociopaths don’t blend in well.”

“Maybe the ones that get diagnosed don’t, but by definition they’re the bottom of the class. The others are too smart to get caught, and real automatons would do even better. Besides, when you get powerful enough, you don’t need to act like other people. Other people start acting like you.”

Sascha whistled. “Wow. Perfect play-actor.”

“Or not so perfect. Sound like anyone we know?”

They may have been talking about someone else entirely, I suppose. But that was as close to a direct reference to Siri Keeton that I heard in all my hours on the grapevine. Nobody else mentioned me, even in passing. That was statistically unlikely, given what I’d just endured in front of them all; someone should have said something. Perhaps Sarasti had ordered them not to discuss it. I didn’t know why. But it was obvious by now that the vampire had been orchestrating their interactions with me for some time. Now I was in hiding, but he knew I’d listen in at some point. Maybe, for some reason, he didn’t want my surveillance—contaminated…

He could have simply locked me out of ConSensus. He hadn’t. Which meant he still wanted me in the loop.

Zombies. Automatons. Fucking sentience.

_For once in your goddamned life, understand something._

He’d said that to me. Or something had. During the assault.

Understand that your life depends on it.

Almost as if he were doing me a favor.

Then he’d left me alone. And had evidently told the others to do the same.

_Are you listening, Keeton?_

And he hadn’t locked me out of ConSensus.

*

Centuries of navel-gazing. Millennia of masturbation. Plato to Descartes to Dawkins to Rhanda. Souls and zombie agents and qualia. Kolmogorov complexity. Consciousness as Divine Spark. Consciousness as electromagnetic field. Consciousness as functional cluster.

I explored it all.

Wegner thought it was an executive summary. Penrose heard it in the singing of caged electrons. Nirretranders said it was a fraud; Kazim called it leakage from a parallel universe. Metzinger wouldn’t even admit it existed. The AIs claimed to have worked it out, then announced they couldn’t explain it to us. Gödel was right after all: no system can fully understand itself.

Not even the synthesists had been able to rotate it down. The load-bearing beams just couldn’t take the strain.

All of them, I began to realize, had missed the point. All those theories, all those drugdreams and experiments and models trying to prove what consciousness was: none to explain what it was good for. None needed: obviously, consciousness makes us what we are. It lets us see the beauty and the ugliness. It elevates us into the exalted realm of the spiritual. Oh, a few outsiders—Dawkins, Keogh, the occasional writer of hackwork fiction who barely achieved obscurity—wondered briefly at the why of it: why not soft computers, and no more? Why should nonsentient systems be inherently inferior? But they never really raised their voices above the crowd. The value of what we are was too trivially self-evident to ever call into serious question.

Yet the questions persisted, in the minds of the laureates, in the angst of every horny fifteen-year-old on the planet. Am I nothing but sparking chemistry? Am I a magnet in the ether? I am more than my eyes, my ears, my tongue; I am the little thing behind those things, the thing looking out from inside. But who looks out from its eyes? What does it reduce to? Who am I? Who am I?_ Who am I?_

What a stupid fucking question. I could have answered it in a second, if Sarasti hadn’t forced me to understand it first.

“Not until we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves.”

—Thoreau

The shame had scoured me and left me hollow.

Comments (0)