An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖

- Author: George Stuart Fullerton

- Performer: -

Book online «An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖». Author George Stuart Fullerton

Now, it should be remarked that the discredit cast upon the argument for other minds has its source in the fact that it does not satisfy a certain assumed standard. What is that standard? It is the standard of proof which we may look for and do look for where we are concerned to establish the existence of material things with the highest degree of certainty.

There are all sorts of indirect ways of proving the existence of material things. We may read about them in a newspaper, and regard them as highly doubtful; we may have the word of a man whom, on the whole, we regard as veracious; we may infer their existence, because we perceive that certain other things exist, and are to be accounted for. Under certain circumstances, however, we may have proof of a different kind: we may see and touch the things themselves. Material things are open to direct inspection. Such a direct inspection constitutes absolute proof, so far as material things are concerned.

But we have no right to set this up as our standard of absolute proof, when we are talking about other minds. In this field it is not proof at all. Anything that can be directly inspected is not another mind. We cannot cast a doubt upon the existence of colors by pointing to the fact that we cannot smell them. If they could be smelt, they would not be colors. We must in each case seek a proof of the appropriate kind.

What have we a right to regard as absolute proof of the existence of another mind? Only this: the analogy upon which we depend in making our inference must be a very close one. As we shall see in the next section, the analogy is sometimes very remote, and we draw the inference with much hesitation, or, perhaps, refuse to draw it at all. It is not, however, the kind of inference that makes the trouble; it is the lack of detailed information that may serve as a basis for inference. Our inference to other minds is unsatisfactory only in so far as we are ignorant of our own minds and bodies and of other bodies. Were our knowledge in these fields complete, we should know without fail the signs of mind, and should know whether an inference were or were not justified.

And justified here means proved—proved in the only sense in which we have a right to ask for proof. No single fact is known that can discredit such a proof. Our doubt is, then, gratuitous and can be dismissed. We may claim that we have verification of the existence of other minds. Such verification, however, must consist in showing that, in any given instance, the signs of mind really are present. It cannot consist in presenting minds for inspection as though they were material things.

One more matter remains to be touched upon in this section. It has doubtless been observed that Mill, in the extract given above, seems to place "feelings," in other words, mental phenomena, between one set of bodily motions and another. He makes them the middle link in a chain whose first and third links are material. The parallelist cannot treat mind in this way. He claims that to make mental phenomena effects or causes of bodily motions is to make them material.

Must, then, the parallelist abandon the argument for other minds? Not at all. The force of the argument lies in interpreting the phenomena presented by other bodies as one knows by experience the phenomena of one's own body must be interpreted. He who concludes that the relation between his own mind and his own body can best be described as a "parallelism," must judge that other men's minds are related to their bodies in the same way. He must treat his neighbor as he treats himself. The argument from analogy remains the same.

42. WHAT OTHER MINDS ARE THERE?—That other men have minds nobody really doubts, as we have seen above. They resemble us so closely, their actions are so analogous to our own, that, although we sometimes give ourselves a good deal of trouble to ascertain what sort of minds they have, we never think of asking ourselves whether they have minds.

Nor does it ever occur to the man who owns a dog, or who drives a horse, to ask himself whether the creature has a mind. He may complain that it has not much of a mind, or he may marvel at its intelligence—his attitude will depend upon the expectations which he has been led to form. But regard the animal as he would regard a bicycle or an automobile, he will not. The brute is not precisely like us, but its actions bear an unmistakable analogy to our own; pleasure and pain, hope and fear, desire and aversion, are so plainly to be read into them that we feel that a man must be "high gravel blind" not to see their significance.

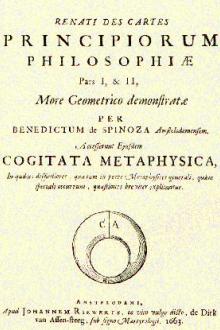

Nevertheless, it has been possible for man, under the prepossession of a mistaken philosophical theory, to assume the whole brute creation to be without consciousness. When Descartes had learned something of the mechanism of the human body, and had placed the human soul—hospes comesque corporis—in the little pineal gland in the midst of the brain, the conception in his mind was not unlike that which we have when we picture to ourselves a locomotive engine with an engineer in its cab. The man gives intelligent direction; but, under some circumstances, the machine can do a good deal in the absence of the man; if it is started, it can run of itself, and to do this, it must go through a series of complicated motions.

Descartes knew that many of the actions performed by the human body are not the result of conscious choice, and that some of them are in direct contravention of the will's commands. The eye protects itself by dropping its lid, when the hand is brought suddenly before it; the foot jerks away from the heated object which it has accidentally touched. The body was seen to be a mechanism relatively independent of the mind, and one rather complete in itself. Joined with a soul, the circle of its functions was conceived to be widened; but even without the assistance of the soul, it was thought that it could keep itself busy, and could do many things that the unreflective might be inclined to attribute to the efficiency of the mind.

The bodies of the brutes Descartes regarded as mechanisms of the same general nature as the human body. He was unwilling to allow a soul to any creature below man, so nothing seemed left to him save to maintain that the brutes are machines without consciousness, and that their apparently purposive actions are to be classed with such human movements as the sudden closing of the eye when it is threatened with the hand. The melancholy results of this doctrine made themselves evident among his followers. Even the mild and pious Malebranche could be brutal to a dog which fawned upon him, under the mistaken notion that it did not really hurt a dog to kick it.

All this reasoning men have long ago set aside. For one thing, it has come to be recognized that there may be consciousness, perhaps rather dim, blind, and fugitive, but still consciousness, which does not get itself recognized as do our clearly conscious purposes and volitions. Many of the actions of man which Descartes was inclined to regard as unaccompanied by consciousness may not, in fact, be really unconscious. And, in the second place, it has come to be realized that we have no right to class all the actions of the brutes with those reflex actions in man which we are accustomed to regard as automatic.

The belief in animal automatism has passed away, it is to be hoped, never to return. That lower animals have minds we must believe. But what sort of minds have they?

It is hard enough to gain an accurate notion of what is going on in a human mind. Men resemble each other more or less closely, but no two are precisely alike, and no two have had exactly the same training. I may misunderstand even the man who lives in the same house with me and is nearly related to me. Does he really suffer and enjoy as acutely as he seems to? or must his words and actions be accepted with a discount? The greater the difference between us, the more danger that I shall misjudge him. It is to be expected that men should misunderstand women; that men and women should misunderstand children; that those who differ in social station, in education, in traditions and habits of life, should be in danger of reading each other as one reads a book in a tongue imperfectly mastered. When these differences are very great, the task is an extremely difficult one. What are the emotions, if he has any, of the Chinaman in the laundry near by? His face seems as difficult of interpretation as are the hieroglyphics that he has pasted up on his window.

When we come to the brutes, the case is distinctly worse. We think that we can attain to some notion of the minds to be attributed to such animals as the ape, the dog, the cat, the horse, and it is not nonsense to speak of an animal psychology. But who will undertake to tell us anything definite of the mind of a fly, a grasshopper, a snail, or a cuttlefish? That they have minds, or something like minds, we must believe; what their minds are like, a prudent man scarcely even attempts to say. In our distribution of minds may we stop short of even the very lowest animal organisms? It seems arbitrary to do so.

More than that; some thoughtful men have been led by the analogy between plant life and animal life to believe that something more or less remotely like the consciousness which we attribute to animals must be attributed also to plants. Upon this belief I shall not dwell, for here we are evidently at the limit of our knowledge, and are making the vaguest of guesses. No one pretends that we have even the beginnings of a plant psychology. At the same time, we must admit that organisms of all sorts do bear some analogy to each other, even if it be a remote one; and we must admit also that we cannot prove plants to be wholly devoid of a rudimentary consciousness of some sort.

As we begin with man and descend the scale of beings, we seem, in the upper part of the series, to be in no doubt that minds exist. Our only question is as to the precise contents of those minds. Further down we begin to ask ourselves whether anything like mind is revealed at all. That this should be so is to be expected. Our argument for other minds is the argument from analogy, and as we move down the scale our analogy grows more and more remote until it seems to fade out altogether. He who harbors doubts as to whether the plants enjoy some sort of psychic life, may well find those doubts intensified when he turns to study the crystal; and when he contemplates inorganic matter he should admit that the thread of his argument has become so attenuated that he cannot find it at all.

43. THE DOCTRINE OF MIND-STUFF.—Nevertheless, there have been those who have attributed something like consciousness even to inorganic matter. If the doctrine of evolution be true, argues Professor Clifford,[4] "we shall have along the line of the human pedigree a series of imperceptible steps connecting inorganic matter with ourselves. To the later members of that series we must undoubtedly ascribe consciousness, although it must, of course, have been simpler than our own. But where are we to stop? In the case of organisms of a certain complexity, consciousness is inferred. As we go back along the line, the complexity of the organism and of its nerve-action insensibly diminishes; and for the first part of our course we see reason to think that the complexity of

Comments (0)