An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖

- Author: George Stuart Fullerton

- Performer: -

Book online «An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖». Author George Stuart Fullerton

Suppose, for example, we take the statement that there must be an adequate cause of all the changes that take place in the world. Can a mere experience of what has been in the past guarantee that this law will hold good in the future? But, when we realize that the world of which we are speaking is nothing more than a world of phenomena, of experiences, and realize further that this whole world is constructed by the mind out of the raw materials furnished by the senses, may we not have a greater confidence in our law? If it is the nature of the mind to connect the phenomena presented to it with one another as cause and effect, may we not maintain that no phenomenon can possibly make its appearance that defies the law in question? How could it appear except under the conditions laid upon all phenomena? If it is our nature to think the world as an orderly one, and if we can know no world save the one we construct ourselves, the orderliness of all the things we can know seems to be guaranteed to us.

It will be noticed that Kant's doctrine has a negative side. He limits our knowledge to phenomena, to experiences, and he is himself, in so far, an empiricist. But in that he finds in experience an order, an arrangement of things, not derived from experience in the usual sense of the word, he is not an empiricist. He has paid his own doctrine the compliment of calling it "criticism," as I have said.

Now, I beg the reader to be here, as elsewhere, on his guard against the associations which attach to words. In calling Kant's doctrine "the critical philosophy," we are in some danger of uncritically assuming and leading others to believe uncritically that it is free from such defects as may be expected to attach to "dogmatism" and to empiricism. Such a position should not be taken until one has made a most careful examination of each of the three types of doctrine, of the assumptions which it makes, and of the rigor with which it draws inferences upon the basis of such assumptions. That we may be the better able to withstand "undue influence," I call attention to the following points:—

(1) We must bear in mind that the attempt to make a critical examination into the foundations of our knowledge, and to determine its scope, is by no means a new thing. Among the Greeks, Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, the Epicureans, and the Skeptics, all attacked the problem. It did not, of course, present itself to these men in the precise form in which it presented itself to Kant, but each and all were concerned to find an answer to the question: Can we know anything with certainty; and, if so, what? They may have failed to be thoroughly critical, but they certainly made the attempt.

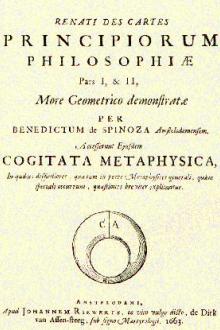

I shall omit mention of the long series of others, who, since that time, have carried on the tradition, and shall speak only of Descartes and Locke, whom I have above brought forward as representatives of the two types of doctrine that Kant contrasts with his own.

To see how strenuously Descartes endeavored to subject his knowledge to a critical scrutiny and to avoid unjustifiable assumptions of any sort, one has only to read that charming little work of genius, the "Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason."

In his youth Descartes was, as he informs us, an eager student; but, when he had finished the whole course of education usually prescribed, he found himself so full of doubts and errors that he did not feel that he had advanced in learning at all. Yet he had been well tutored, and was considered as bright in mind as others. He was led to judge his neighbor by himself, and to conclude that there existed no such certain science as he had been taught to suppose.

Having ripened with years and experience, Descartes set about the task of which I have spoken above, the task of sweeping away the whole body of his opinions and of attempting a general and systematic reconstruction. So important a work should be, he thought, approached with circumspection; hence, he formulated certain Rules of Method.

"The first," he writes, "was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is, carefully to avoid haste and prejudice, and to include nothing more in my judgments than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all reason for doubt."

Such was our philosopher's design, and such the spirit in which he set about it. We have seen the result above. It is as if Descartes had decided that a certain room full of people did not appear to be free from suspicious characters, and had cleared out every one, afterwards posting himself at the door to readmit only those who proved themselves worthy. When we examine those who succeeded in passing muster, we discover he has favored all his old friends. He simply cannot doubt them; are they not vouched for by the "natural light"? Nevertheless, we must not forget that Descartes sifted his congregation with much travail of spirit. He did try to be critical.

As for John Locke, he reveals in the "Epistle to the Reader," which stands as a preface to the "Essay," the critical spirit in which his work was taken up. "Were it fit to trouble thee," he writes, "with the history of this Essay, I should tell thee, that five or six friends meeting at my chamber, and discoursing on a subject very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the difficulties that rose on every side. After we had a while puzzled ourselves, without coming any nearer a resolution of those doubts which perplexed us, it came into my thoughts, that we took a wrong course; and that before we set ourselves upon inquiries of that nature, it was necessary to examine our own abilities, and to see what objects our understandings were, or were not, fitted to deal with."

This problem, proposed by himself to his little circle of friends, Locke attacked with earnestness, and as a result he brought out many years later the work which has since become so famous. The book is literally a critique of the reason, although a very different critique from that worked out by Kant.

"If, by this inquiry into the nature of the understanding," says Locke, "I can discover the powers thereof, how far they reach, to what things they are in any degree proportionate, and where they fail us; I suppose it may be of use to prevail with the busy mind of man to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its comprehension; to stop when it is at the utmost extent of its tether; and to sit down in a quiet ignorance of those things which upon examination are found to be beyond the reach of our capacities." [2]

To the difficulties of the task our author is fully alive: "The understanding, like the eye, whilst it makes us see and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself; and it requires art and pains to set it at a distance, and make it its own object. But whatever be the difficulties that lie in the way of this inquiry, whatever it be that keeps us so much in the dark to ourselves, sure I am that all the light we can let in upon our own minds, all the acquaintance we can make with our own understandings, will not only be very pleasant, but bring us great advantage, in directing our thoughts in the search, of other things." [3]

(2) Thus, many men have attempted to produce a critical philosophy, and in much the same sense as that in which Kant uses the words. Those who have come after them have decided that they were not sufficiently critical, that they have made unjustifiable assumptions. When we come to read Kant, we will, if we have read the history of philosophy with profit, not forget to ask ourselves if he has not sinned in the same way.

For example, we will ask;—

(a) Was Kant right in maintaining that we find in experience synthetic judgments (section 51) that are not founded upon experience, but yield such information as is beyond the reach of the empiricist? There are those who think that the judgments to which he alludes in evidence of his contention—the mathematical, for instance—are not of this character.

(b) Was he justified in assuming that all the ordering of our world is due to the activity of mind, and that merely the raw material is "given" us through the senses? There are many who demur against such a statement, and hold that it is, if not in all senses untrue, at least highly misleading, since it seems to argue that there is no really external world at all. Moreover, they claim that the doctrine is neither self-evident nor susceptible of proper proof.

(c) Was Kant justified in assuming that, even if we attribute the "form" or arrangement of the world we know to the native activity of the mind, the necessity and universality of our knowledge is assured? Let us grant that the proposition, whatever happens must have an adequate cause, is a "form of thought." What guarantee have we that the "forms of thought" must ever remain changeless? If it is an assumption for the empiricist to declare that what has been true in the past will be true in the future, that earlier experiences of the world will not be contradicted by later; what is it for the Kantian to maintain that the order which he finds in his experience will necessarily and always be the order of all future experiences? Transferring an assumption to the field of mind does not make it less of an assumption.

Thus, it does not seem unreasonable to charge Kant with being a good deal of a rationalist. He tried to confine our knowledge to the field of experience, it is true; but he made a number of assumptions as to the nature of experience which certainly do not shine by their own light, and which many thoughtful persons regard as incapable of justification.

Kant's famous successors in the German philosophy, Fichte (1762-1814), Schelling (1775-1854), Hegel (1770-1831), and Schopenhauer (1788-1860), all received their impulse from the "critical philosophy," and yet each developed his doctrine in a relatively independent way.

I cannot here take the space to characterize the systems of these men; I may merely remark that all of them contrast strongly in doctrine and method with the British philosophers mentioned in the last section, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Mill. They are un-empirical, if one may use such a word; and, to one accustomed to reading the English philosophy, they seem ever ready to spread their wings and hazard the boldest of flights without a proper realization of the thinness of the atmosphere in which they must support themselves.

However, no matter what may be one's opinion of the actual results attained by these German philosophers, one must frankly admit that no one who wishes to understand clearly the development of speculative thought can afford to dispense with a careful reading of them. Much even of the English philosophy of our own day must remain obscure to those who have not looked into their pages. Thus, the thought of Kant and Hegel molded the thought of Thomas Hill Green (1836-1882) and of the brothers Caird; and their influence has made itself widely felt both in England and in America. One cannot criticise intelligently books written from their standpoint, unless one knows how the authors came by their doctrine and out of what it has been developed.

63. CRITICAL EMPIRICISM.—We have seen that the trouble with the rationalists seemed to be that they made an appeal to "eternal truths," which those who followed them could not admit to be eternal truths at all. They proceeded on a basis of

Comments (0)