An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖

- Author: George Stuart Fullerton

- Performer: -

Book online «An Introduction to Philosophy by George Stuart Fullerton (bookreader TXT) 📖». Author George Stuart Fullerton

This should be evident from what has been said earlier in this chapter and elsewhere in this book. Let us bear in mind that a philosopher draws his material from two sources. First of all, he has the experience of the mind and the world which is the common property of us all. But it is, as we have seen, by no means easy to use this material. It is vastly difficult to reflect. It is fatally easy to misconceive what presents itself in our experience. With the most earnest effort to describe what lies before us, we give a false description, and we mislead ourselves and others.

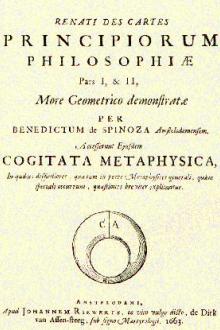

In the second place, the philosopher has the interpretations of experience which he has inherited from his predecessors. The influence of these is enormous. Each age has, to a large extent, its problems already formulated or half formulated for it. Every man must have ancestors, of some sort, if he is to appear upon this earthly stage at all; and a wholly independent philosopher is as impossible a creature as an ancestorless man. We have seen how Descartes (section 60) tried to repudiate his debt to the past, and how little successful he was in doing so.

Now, we make a mistake if we overlook the genius of the individual thinker. The history of speculative thought has many times taken a turn which can only be accounted for by taking into consideration the genius for reflective thought possessed by some great mind. In the crucible of such an intellect, old truths take on a new aspect, familiar facts acquire a new and a richer meaning. But we also make a mistake if we fail to see in the writings of such a man one of the stages which has been reached in the gradual evolution of human thought, if we fail to realize that each philosophy is to a great extent the product of the past.

When one comes to understand these things, the history of philosophy no longer presents itself as a mere agglomeration of arbitrary and independent systems. And an attentive reading gives us a further key to the interpretation of what seemed inexplicable. We find that there may be distinct and different streams of thought, which, for a while, run parallel without commingling their waters. For centuries the Epicurean followed his own tradition, and walked in the footsteps of his own master. The Stoic was of sterner stuff, and he chose to travel another path. To this day there are adherents of the old church philosophy, Neo-Scholastics, whose ways of thinking can only be understood when we have some knowledge of Aristotle and of his influence upon men during the Middle Ages. We ourselves may be Kantians or Hegelians, and the man at our elbow may recognize as his spiritual father Comte or Spencer.

It does not follow that, because one system follows another in chronological order, it is its lineal descendant. But some ancestor a system always has, and if we have the requisite learning and ingenuity, we need not find it impossible to explain why this thinker or that was influenced to give his thought the peculiar turn that characterizes it. Sometimes many influences have conspired to attain the result, and it is no small pleasure to address oneself to the task of disentangling the threads which enter into the fabric.

Moreover, as we read thus with discrimination, we begin to see that the great men of the past have not spoken without appearing to have sufficient reason for their utterances in the light of the times in which they lived. We may make it a rule that, when they seem to be speaking arbitrarily, to be laying before us reasonings that are not reasonings, dogmas for which no excuse seems to be offered, the fault lies in our lack of comprehension. Until we can understand how a man, living in a certain century, and breathing a certain moral and intellectual atmosphere, could have said what he did, we should assume that we have read his words, but not his real thought. For the latter there is always a psychological, if not a logical, justification.

And this brings me to the question of the language in which the philosophers have expressed their thoughts. The more attentively one reads the history of philosophy, the clearer it becomes that the number of problems with which the philosophers have occupied themselves is not overwhelmingly great. If each philosophy which confronts us seems to us quite new and strange, it is because we have not arrived at the stage at which it is possible for us to recognize old friends with new faces. The same old problems, the problems which must ever present themselves to reflective thought, recur again and again. The form is more or less changed, and the answers which are given to them are not, of course, always the same. Each age expresses itself in a somewhat different way. But sometimes the solution proposed for a given problem is almost the same in substance, even when the two thinkers we are contrasting belong to centuries which lie far apart. In this case, only our own inability to strip off the husk and reach the fruit itself prevents us from seeing that we have before us nothing really new.

Thus, if we read the history of philosophy with patience and with discrimination, it grows luminous. We come to feel nearer to the men of the past. We see that we may learn from their successes and from their failures; and if we are capable of drawing a moral at all, we apply the lesson to ourselves.

CHAPTER XXIV SOME PRACTICAL ADMONITIONS88. BE PREPARED TO ENTER UPON A NEW WAY OF LOOKING AT THINGS.—We have seen that reflective thought tries to analyze experience and to attain to a clear view of the elements that make it up—to realize vividly what is the very texture of the known world, and what is the nature of knowledge. It is possible to live to old age, as many do, without even a suspicion that there may be such a knowledge as this, and nevertheless to possess a large measure of rather vague but very serviceable information about both minds and bodies.

It is something of a shock to learn that a multitude of questions may be asked touching the most familiar things in our experience, and that our comprehension of those things may be so vague that we grope in vain for an answer. Space, time, matter, minds, realities,—with these things we have to do every day. Can it be that we do not know what they are? Then we must be blind, indeed. How shall we set about enlightening our ignorance?

Not as we have enlightened our ignorance heretofore. We have added fact to fact; but our task now is to gain a new light on all facts, to see them from a different point of view; not so much to extend our knowledge as to deepen it.

It seems scarcely necessary to point out that our world, when looked at for the first time in this new way, may seem to be a new and strange world. The real things of our experience may appear to melt away, to be dissolved by reflection into mere shadows and unrealities. Well do I remember the consternation with which, when almost a schoolboy, I first made my acquaintance with John Stuart Mill's doctrine that the things about us are "permanent possibilities of sensation." To Mill, of course, chairs and tables were still chairs and tables, but to me they became ghosts, inhabitants of a phantom world, to find oneself in which was a matter of the gravest concern.

I suspect that this sense of the unreality of things comes often to those who have entered upon the path of reflection, It may be a comfort to such to realize that it is rather a thing to be expected. How can one feel at home in a world which one has entered for the first time? One cannot become a philosopher and remain exactly the man that one was before. Men have tried to do it,—Thomas Reid is a notable instance (section 50); but the result is that one simply does not become a philosopher. It is not possible to gain a new and a deeper insight into the nature of things, and yet to see things just as one saw them before one attained to this.

If, then, we are willing to study philosophy at all, we must be willing to embrace new views of the world, if there seem to be good reasons for so doing. And if at first we suffer from a sense of bewilderment, we must have patience, and must wait to see whether time and practice may not do something toward removing our distress. It may be that we have only half understood what has been revealed to us.

89. BE WILLING TO CONSIDER POSSIBILITIES WHICH AT FIRST STRIKE ONE AS ABSURD.—It must be confessed that the philosophers have sometimes brought forward doctrines which seem repellent to good sense, and little in harmony with the experience of the world which we have all our lives enjoyed. Shall we on this account turn our backs upon them and refuse them an impartial hearing?

Thus, the idealist maintains that there is no existence save psychical existence; that the material things about us are really mental things. One of the forms taken by this doctrine is that alluded to above, that things are permanent possibilities of sensation.

I think it can hardly be denied that this sounds out of harmony with the common opinion of mankind. Men do not hesitate to distinguish between minds and material things, nor do they believe that material things exist only in minds. That dreams and hallucinations exist only in minds they are very willing to admit; but they will not admit that this is true of such things as real chairs and tables. And if we ask them why they take such a position, they fall back upon what seems given in experience.

Now, as the reader of the earlier chapters has seen, I think that the plain man is more nearly right in his opinion touching the existence of a world of non-mental things than is the idealistic philosopher. The latter has seen a truth and misconceived it, thus losing some truth that he had before he began to reflect. The former has not seen the truth which has impressed the idealist, and he has held on to that vague recognition that there are two orders of things given in our experience, the physical and the mental, which seems to us so unmistakable a fact until we fall into the hands of the philosophers.

But all this does not prove that we have a right simply to fall back upon "common sense," and refuse to listen to the idealist. The deliverances of unreflective common sense are vague in the extreme; and though it may seem to assure us that there is a world of things non-mental, its account of that world is confused and incoherent. He who must depend on common sense alone can find no answer to the idealists; he refuses to follow them, but he cannot refute them. He is reduced to dogmatic denial.

This is in itself an uncomfortable position. And when we add to this the reflection that such a man loses the truth which the idealist emphasizes, the truth that the external world of which we speak must be, if we are to know it at all, a world revealed to our senses, a world given in our experience, we see that he who stops his ears remains in ignorance. The fact is that the man who has never weighed the evidence that impresses the idealist is not able to see clearly what is meant by that external world in which we all incline to put such faith. We may say that he feels a truth blindly, but does not see it.

Let us take another illustration. If there is one thing that we feel to be as sure as the existence of the external world, it is that

Comments (0)