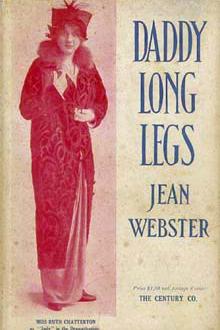

Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster (best way to read an ebook .TXT) 📖

- Author: Jean Webster

- Performer: 0140374558

Book online «Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster (best way to read an ebook .TXT) 📖». Author Jean Webster

I sat up half of last night reading Jane Eyre. Are you old enough, Daddy, to remember sixty years ago? And, if so, did people talk that way?

The haughty Lady Blanche says to the footman, `Stop your chattering, knave, and do my bidding.’ Mr. Rochester talks about the metal welkin when he means the sky; and as for the mad woman who laughs like a hyena and sets fire to bed curtains and tears up wedding veils and BITES—it’s melodrama of the purest, but just the same, you read and read and read. I can’t see how any girl could have written such a book, especially any girl who was brought up in a churchyard. There’s something about those Brontes that fascinates me. Their books, their lives, their spirit. Where did they get it? When I was reading about little Jane’s troubles in the charity school, I got so angry that I had to go out and take a walk. I understood exactly how she felt. Having known Mrs. Lippett, I could see Mr. Brocklehurst.

Don’t be outraged, Daddy. I am not intimating that the John Grier Home was like the Lowood Institute. We had plenty to eat and plenty to wear, sufficient water to wash in, and a furnace in the cellar. But there was one deadly likeness. Our lives were absolutely monotonous and uneventful. Nothing nice ever happened, except ice-cream on Sundays, and even that was regular. In all the eighteen years I was there I only had one adventure—when the woodshed burned. We had to get up in the night and dress so as to be ready in case the house should catch. But it didn’t catch and we went back to bed.

Everybody likes a few surprises; it’s a perfectly natural human craving. But I never had one until Mrs. Lippett called me to the office to tell me that Mr. John Smith was going to send me to college. And then she broke the news so gradually that it just barely shocked me.

You know, Daddy, I think that the most necessary quality for any person to have is imagination. It makes people able to put themselves in other people’s places. It makes them kind and sympathetic and understanding. It ought to be cultivated in children. But the John Grier Home instantly stamped out the slightest flicker that appeared. Duty was the one quality that was encouraged. I don’t think children ought to know the meaning of the word; it’s odious, detestable. They ought to do everything from love.

Wait until you see the orphan asylum that I am going to be the head of! It’s my favourite play at night before I go to sleep. I plan it out to the littlest detail—the meals and clothes and study and amusements and punishments; for even my superior orphans are sometimes bad.

But anyway, they are going to be happy. I think that every one, no matter how many troubles he may have when he grows up, ought to have a happy childhood to look back upon. And if I ever have any children of my own, no matter how unhappy I may be, I am not going to let them have any cares until they grow up.

(There goes the chapel bell—I’ll finish this letter sometime).

Thursday

When I came in from laboratory this afternoon, I found a squirrel sitting on the tea table helping himself to almonds. These are the kind of callers we entertain now that warm weather has come and the windows stay open—

Saturday morning Perhaps you think, last night being Friday, with no classes today, that I passed a nice quiet, readable evening with the set of Stevenson that I bought with my prize money? But if so, you’ve never attended a girls’ college, Daddy dear. Six friends dropped in to make fudge, and one of them dropped the fudge—while it was still liquid— right in the middle of our best rug. We shall never be able to clean up the mess.

I haven’t mentioned any lessons of late; but we are still having them every day. It’s sort of a relief though, to get away from them and discuss life in the large—rather one-sided discussions that you and I hold, but that’s your own fault. You are welcome to answer back any time you choose.

I’ve been writing this letter off and on for three days, and I fear by now vous etes bien bored! Goodbye, nice Mr. Man, Judy

Mr. Daddy-Long-Legs Smith,

SIR: Having completed the study of argumentation and the science of dividing a thesis into heads, I have decided to adopt the following form for letter-writing. It contains all necessary facts, but no unnecessary verbiage.

I. We had written examinations this week in: A. Chemistry. B. History.

II. A new dormitory is being built. A. Its material is: (a) red brick. (b) grey stone. B. Its capacity will be: (a) one dean, five instructors. (b) two hundred girls. (c) one housekeeper, three cooks, twenty waitresses, twenty chambermaids.

III. We had junket for dessert tonight.

IV. I am writing a special topic upon the Sources of Shakespeare’s Plays.

V. Lou McMahon slipped and fell this afternoon at basket ball, and she: A. Dislocated her shoulder. B. Bruised her knee.

VI. I have a new hat trimmed with: A. Blue velvet ribbon. B. Two blue quills. C. Three red pompoms.

VII. It is half past nine.

VIII. Good night. Judy

2nd June Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,You will never guess the nice thing that has happened.

The McBrides have asked me to spend the summer at their camp in the Adirondacks! They belong to a sort of club on a lovely little lake in the middle of the woods. The different members have houses made of logs dotted about among the trees, and they go canoeing on the lake, and take long walks through trails to other camps, and have dances once a week in the club house—Jimmie McBride is going to have a college friend visiting him part of the summer, so you see we shall have plenty of men to dance with.

Wasn’t it sweet of Mrs. McBride to ask me? It appears that she liked me when I was there for Christmas.

Please excuse this being short. It isn’t a real letter; it’s just to let you know that I’m disposed of for the summer. Yours, In a VERY contented frame of mind, Judy

5th June Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,Your secretary man has just written to me saying that Mr. Smith prefers that I should not accept Mrs. McBride’s invitation, but should return to Lock Willow the same as last summer.

Why, why, WHY, Daddy?

You don’t understand about it. Mrs. McBride does want me, really and truly. I’m not the least bit of trouble in the house. I’m a help. They don’t take up many servants, and Sallie an I can do lots of useful things. It’s a fine chance for me to learn housekeeping. Every woman ought to understand it, an I only know asylum-keeping.

There aren’t any girls our age at the camp, and Mrs. McBride wants me for a companion for Sallie. We are planning to do a lot of reading together. We are going to read all of the books for next year’s English and sociology. The Professor said it would be a great help if we would get our reading finished in the summer; and it’s so much easier to remember it if we read together and talk it over.

Just to live in the same house with Sallie’s mother is an education. She’s the most interesting, entertaining, companionable, charming woman in the world; she knows everything. Think how many summers I’ve spent with Mrs. Lippett and how I’ll appreciate the contrast. You needn’t be afraid that I’ll be crowding them, for their house is made of rubber. When they have a lot of company, they just sprinkle tents about in the woods and turn the boys outside. It’s going to be such a nice, healthy summer exercising out of doors every minute. Jimmie McBride is going to teach me how to ride horseback and paddle a canoe, and how to shoot and—oh, lots of things I ought to know. It’s the kind of nice, jolly, carefree time that I’ve never had; and I think every girl deserves it once in her life. Of course I’ll do exactly as you say, but please, PLEASE let me go, Daddy. I’ve never wanted anything so much.

This isn’t Jerusha Abbott, the future great author, writing to you. It’s just Judy—a girl.

9th June Mr. John Smith,

SIR: Yours of the 7th inst. at hand. In compliance with the instructions received through your secretary, I leave on Friday next to spend the summer at Lock Willow Farm.

I hope always to remain, (Miss) Jerusha Abbott

LOCK WILLOW FARM, 3rd August Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

It has been nearly two months since I wrote, which wasn’t nice of me, I know, but I haven’t loved you much this summer—you see I’m being frank!

You can’t imagine how disappointed I was at having to give up the McBrides’ camp. Of course I know that you’re my guardian, and that I have to regard your wishes in all matters, but I couldn’t see any REASON. It was so distinctly the best thing that could have happened to me. If I had been Daddy, and you had been Judy, I should have said, `Bless yo my child, run along and have a good time; see lots of new people and learn lots of new things; live out of doors, and get strong and well and rested for a year of hard work.’

But not at all! Just a curt line from your secretary ordering me to Lock Willow.

It’s the impersonality of your commands that hurts my feelings. It seems as though, if you felt the tiniest little bit for me the way I feel for you, you’d sometimes send me a message that you’d written with your own hand, instead of those beastly typewritten secretary’s notes. If there were the slightest hint that you cared, I’d do anything on earth to please you.

I know that I was to write nice, long, detailed letters without ever expecting any answer. You’re living up to your side of the bargain— I’m being educated—and I suppose you’re thinking I’m not living up to mine!

But, Daddy, it is a hard bargain. It is, really. I’m so awfully lonely. You are the only person I have to care for, and you are so shadowy. You’re just an imaginary man that I’ve made up—and probably the real YOU isn’t a bit like my imaginary YOU. But you did once, when I was ill in the infirmary, send me a message, and now, when I am feeling awfully forgotten, I get out your card and read it over.

I don’t think I am telling you at all what I started to say, which was this:

Although my feelings are still hurt, for it is very humiliating to be picked up and moved about by an arbitrary, peremptory, unreasonable, omnipotent, invisible Providence, still, when a man has been as kind and generous and thoughtful as you have heretofore been towards me, I suppose he has a right to be an arbitrary, peremptory, unreasonable, invisible Providence if he chooses, and so— I’ll forgive you and be cheerful again. But I still don’t enjoy getting Sallie’s letters about the good times they are having in camp!

However—we will draw a veil over that and begin again.

I’ve been writing and writing this summer; four short stories finished and sent to four different

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Comments (0)