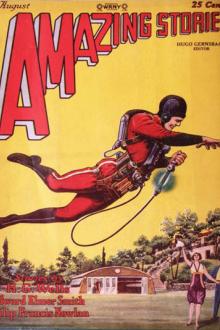

Genre Science Fiction. Page - 14

The old Rebel cursed. "Gehenna of a big crop; we're up to our necks in melons. This time next year we'll be washing our feet in brandy."

"Hold onto it and age it; you ought to see what they charge for a drink of Poictesme brandy on Terra."

"This isn't Terra, and we aren't selling it by the drink," Colonel Zareff said. "We're selling it at Storisende Spaceport, for what the freighter captains pay us. You've been away too long, Conn. You've forgotten what it's like to live in a poor-house."

The cargo was coming off, now. Cask staves, and more cask staves. Zareff swore bitterly at the sight, and then they started toward the wide doors of the shipping floor, inside the Airlines Building. Outgoing cargo was beginning to come out; casks of brandy, of course, and a lot of boxes and crates, painted light blue and bearing the yellow trefoil of the Third Fleet-Army Force and the eight-pointed red star of Ordnance. Cases of rifles; square boxes of ammunition; crated auto-cannon. Conn turned to hi

he worked it to make us think him a nut. He certainly is clever. I take off my hat to him--he's a wonder!"

"And what is your idea? Where do we come in?"

"You come in by getting that solution away from Seaton and Crane, and furnishing the money to develop the stuff and to build, under my direction, such a power-plant as the world never saw before."

"Why get that particular solution? Couldn't we buy up some platinum wastes and refine them?"

"Not a chance," replied the scientist. "We have refined platinum residues for years, and never found anything like that before. It is my idea that the stuff, whatever it is, was present in some particular lot of platinum in considerable quantities as an impurity. Seaton hasn't all of it there is in the world, of course, but the chance of finding any more of it without knowing exactly what it is or how it reacts is extremely slight. Besides, we must have exclusive control. How could we make any money out of it if Crane operates a rival company and

to have? What clothing, if any, do you wish me to wear? What name would you like me to answer to?"

Mike looked at the clock on the wall. It was 3:20 PM. He counted off six hours on his fingers—9:20. He sat down on the white sofa that was almost never used and looked at the shapely nude robot. With a wry smile, he realized that he could sit and stare at it for the next six hours, or he could get up and do something. He went back to the family room, picked up the texTee, and flipped open Moby Dick, but he didn't read any more of it. Instead he turned the select dial to the bookstore and typed in "names". The titles of half a dozen books appeared including "The Name Book", "The Secret Universe of Names", and "The Baby Name Wizard". He selected the last book of the six: "Virtue Names". It took about twenty seconds for the book to download to the texTee. Looking back to the screen, Mike turned to the first page of the name book. The first name was Agape. Agape? The book said that it had something to

the New Jardeen Incident."

A frozen silence followed the last five words. Hunter thought, So that's what the little weasel was fishing for....

Rockford quietly laid down his fork. Val's face turned grim. Lyla looked up in quick alarm and said to Narf:

"Let's not--"

"Don't misunderstand me, gentlemen," Narf's loud voice went on. "I believe the commander of the Terran cruiser wouldn't have ordered it to fire upon the Verdam cruiser over a neutral world such as New Jardeen if he had been his rational self. Cold-war battle nerves. So he shot down the Verdam cruiser and its nuclear converters exploded when it fell in the center of Colony City. Force of a hydrogen bomb--forty thousand innocent people gone in a microsecond. Not the commander's fault, really--fault of the military system that failed to screen out its unstable officers."

"Yes, your lordship. But is it possible"--Sonig spoke very thoughtfully--"for a political power, which is of such a nature that i

ter took up the portfolio, opened it, put it down, hesitated, seemed about to speak. "Perhaps," he whispered doubtfully. Presently he glanced at the door and back to the figure. Then he stole on tiptoe out of the room, glancing at his companion after each elaborate pace.

He closed the door noiselessly. The house door was standing open, and he went out beyond the porch, and stood where the monkshood rose at the corner of the garden bed. From this point he could see the stranger through the open window, still and dim, sitting head on hand. He had not moved.

A number of children going along the road stopped and regarded the artist curiously. A boatman exchanged civilities with him. He felt that possibly his circumspect attitude and position looked peculiar and unaccountable. Smoking, perhaps, might seem more natural. He drew pipe and pouch from his pocket, filled the pipe slowly.

"I wonder," ... he said, with a scarcely perceptible loss of complacency. "At any rate one must give him a chance

ow long ago? He marveled at how the priestesses had managed to keep this one icon in pristine condition. He could understand why the pilgrims felt

the magic in it, even if he did not.

"Estamos refugiados en una zona de apagon." The priestess, in a high, squeaky voice, rained down nonsense from the balcony. "Nuestras casas desarraigados, arrastrando raÃces profundas de concreta, fibrosas con tubos y conectores, giran y saltan a las fluctuaciones del campo de gravitacion. Â La gente tienen miedo." She droned on like that, and Donal found himself scanning the crowd, idly yet thoroughly, to see if anyone unsavory might have snuck through the front gate.

There had been a small group, armed with pieces of metal no larger than their fingernails but sharpened enough to cut, and they had slipped in and managed to kill a handful of guests and Castle workers before they were hacked to bits. The memory was bitterly fresh. But no one in the group of soft, milli

"So much pettiness," he explained; "so much intrigue! And really, when one has an idea--a novel, fertilising idea--I don't want to be uncharitable, but--"

I am a man who believes in impulses. I made what was perhaps a rash proposition. But you must remember, that I had been alone, play-writing in Lympne, for fourteen days, and my compunction for his ruined walk still hung about me. "Why not," said I, "make this your new habit? In the place of the one I spoilt? At least, until we can settle about the bungalow. What you want is to turn over your work in your mind. That you have always done during your afternoon walk. Unfortunately that's over--you can't get things back as they were. But why not come and talk about your work to me; use me as a sort of wall against which you may throw your thoughts and catch t

"Running this project is my business, not yours; and if there's any one thing in the entire universe it does not need, it's a female exhibitionist. Besides your obvious qualifications to be one of the Eves in case of Ultimate Contingency...." he broke off and stared at her, his contemptuous gaze traveling slowly, dissectingly, from her toes to the topmost wave of her hair-do.

"Forty-two, twenty, forty?" he sneered.

"You flatter me." Her glare was an almost tangible force; her voice was controlled fury.

"Thirty-nine, twenty-two, thirty-five. Five seven. One thirty-five. If any of it's any of your business, which it isn't. You should be discussing brains and ability, not vital statistics."

"Brains? You? No, I'll take that back. As a Prime, you have got a brain--one that really works. What do you think you're good for on this project? What can you do?"

"I can do anything any man ever born can do, and do it better!"

"Okay. Compute a Gunther

ill be most pleased as she ships you off to the state hospital at Osawatomie!"

Buddy took a few steps back from the camera and shifted the Strat into playing position. "That's all the sign says, but I'll repeat the address in a while in case nobody's listening right now." He looked up and around, as if watching an airplane cross the sky. "Seems like I'm in a big glass bubble, and I can't tell where the light's coming from. It's a little chilly, and I sure hope I don't have to be here long. In the meantime, here's one for your family audience, Mr. Sullivan." He struck a hard chord and began singing "Oh, Boy!" in a wild shout.

I remote-controlled the Sony into blank-screened silence. Poor Buddy. He had seemed to be surrounded by nothing worse than stars and shadows, but I remembered enough from my Introductory Astronomy course to know better. Ganymede was an immense ice ball strewn with occasional patches of meteoric rock, and its surface was constantly bombarded by vicious streams of protons and

Call him Cobb Anderson2. Cobb2 didn't drink. Cobb envied him. He hadn't had a completely sober day since he had the operation and left his wife.

"How did you get here?"

The robot waved a hand palm up. Cobb liked the way the gesture looked on someone else. "I can't tell you," the machine said. "You know how most people feel about us."

Cobb chuckled his agreement. He should know. At first the public had been delighted that Cobb's moon-robots had evolved into intelligent boppers. That had been before Ralph Numbers had led the 2001 revolt. After the revolt, Cobb had been tried for treason. He focused back on the present.

"If you're a bopper, then how can you be... here?" Cobb waved his hand in a vague circle, taking in the hot sand and the setting sun. "It's too hot. All the boppers I know of are based on supercooled circuits. Do you have a refrigeration unit hidden in your stomach?"

Anderson2 made another familiar hand-gesture. "I'm not going to tell you yet, Cobb. Later you'