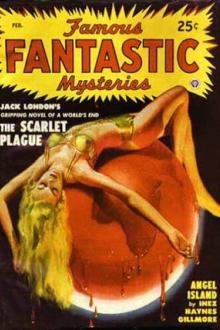

Genre Science Fiction. Page - 15

The inadequate boat finally arrived at a precarious landing, thenatives, waist-deep in the surf, assisting. I was carried ashore,and while the evening meal was being prepared, I wandered to andfro along the rocky, shattered shore. Bits of surf-harriedbeach clove the worn granite, or whatever the rocks of CapeFarewell may be composed of, and as I followed the ebbing tidedown one of these soft stretches, I saw the thing. Were oneto bump into a Bengal tiger in the ravine behind the BiminiBaths, one could be no more surprised than was I to see aperfectly good quart thermos bottle turning and twisting in thesurf of Cape Farewell at the southern extremity of Greenland.I rescued it, but I was soaked above the knees doing it; and thenI sat down in the sand and opened it, and in the long twilightread the manuscript, neatly written and tightly folded, which wasits contents.

You have read the opening paragraph, and if you are an imaginativeidiot like myself, you will want to read the rest of it; so

of libertine. Woman, first and foremost, washis game. Every woman attracted him. No woman held him. Any new woman,however plain, immediately eclipsed her predecessor, however beautiful.The fact that amorous interests took precedence over all others wasquite enough to make him vaguely unpopular with men. But as in addition,he was a physical type which many women find interesting, it is likelythat an instinctive sex-jealousy, unformulated but inevitable, biassedtheir judgment. He was a typical business man; but in appearance herepresented the conventional idea of an artist. Tall, muscular,graceful, hair thick and a little wavy, beard pointed and golden-brown,eyes liquid and long-lashed, women called him "interesting." There was,moreover, always a slight touch of the picturesque in his clothes; hewas master of the small amatory ruses which delight flirtatious women.

In brief, men were always divided in their own minds in regard to RalphAddington. They knew that, constantly, he broke every canon

not monsters. That one was just trying to protect itself."

"What was that silver stuff? It looked alive!"

"Dad told me about that one time. The mothers protect themselves with it. He said the stuff goes towards whatever's wettest. He said he saw somebody get covered with it once; he died, but the stuff was still on him, so they got it off by dropping the body in a horse trough."

Emmy shuddered. "That was an awful chance. Don't do anything like that again, hear?"

The excitement was over, and the rest of the crowd began to disperse. "Come, let's get you cleaned up," she said, towing him in the direction of the kitchens.

As they were rounding the reflecting pool, Jordan heard the sudden thunder of hooves, saw the dust fountaining up from them. They were headed straight for him.

"Look out!" He whirled, pushing Emmy out of the way. She shrieked and fell in the pool.

The sound vanished; the dust blinked out of existence.

There were no horses. The courtyard was

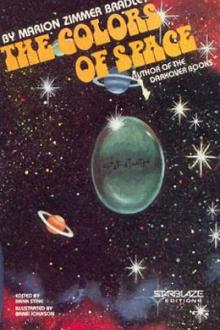

the Lhari that way, yet they're as human as we are! Slaves of the Lhari!"

Bart felt the involuntary surge of anger, instantly controlled. "It's not that way at all. My mother was a Mentorian, remember. She made five cruises on a Lhari ship before she married my father."

Tommy sighed. "I guess I'm just jealous--to think the Mentorians can sign on the Lhari ship as crew, while you and I will never pilot a ship between the stars. What did she do?"

"She was a mathematician. Before the Lhari met up with men, they used a system of mathematics as clumsy as the old Roman numerals. You have to admire them, when you realize that they learned stellar navigation with their old system, though most ships use human math now. And of course, you know their eyes aren't like ours. Among other things, they're color-blind. They see everything in shades of black or white or gray.

"So they found out that humans aboard their ships were useful. You remember how humans, in the early days in space,

at the earth on my diagram, and then at myself, and then, to clinch it, I pointed to myself and then to the earth itself shining bright green almost at the zenith.

"Tweel set up such an excited clacking that I was certain he understood. He jumped up and down, and suddenly he pointed at himself and then at the sky, and then at himself and at the sky again. He pointed at his middle and then at Arcturus, at his head and then at Spica, at his feet and then at half a dozen stars, while I just gaped at him. Then, all of a sudden, he gave a tremendous leap. Man, what a hop! He shot straight up into the starlight, seventy-five feet if an inch! I saw him silhouetted against the sky, saw him turn and come down at me head first, and land smack on his beak like a javelin! There he stuck square in the center of my sun-circle in the sand--a bull's eye!"

"Nuts!" observed the captain. "Plain nuts!"

"That's what I thought, too! I just stared at him open-mouthed while he pulled his head out of the sand an

ti, which is intouch with each one of the four globes and a part of it. Thesame is true of any aggregation of prakriti--of the earth itselfand of all things in it, including man. As there are fouratoms in each one, so there are four earths, four globes,consubstantial, one for each of the four elements, and in touchwith it. One is formed of prakritic atoms--the globe we know;another, of the ether forming their envelopes; another, of theprana envelopes of ether, and a fourth of the manasa around thepranic atom. They are not "skins"; they are consubstantial.And what is true of atoms or globes is true of animals. Each hasfour "material" bodies, with each body on the corresponding globe--whether of the earth or of the Universe. This is the physicalbasis of the famous "chain of seven globes" that is such astumbling-block in Hindu metaphysics. The spirit passes throughfour to get in and three to get out--seven in all. The Hinduunderstands without explanation. He understands his physics.

se they were so near. On every side the middle distance was crowded with swarms and streams of stars. But even these now seemed near; for the Milky Way had receded into an incomparably greater distance. And through gaps in its nearer parts appeared vista beyond vista of luminous mists, and deep perspectives of stellar populations.

The universe in which fate had set me was no spangled chamber, but a perceived vortex of star-streams. No! It was more. Peering between the stars into the outer darkness, I saw also, as mere flecks and points of light, other such vortices, such galaxies, sparsely scattered in the void, depth beyond depth, so far afield that even the eye of imagination could find no limits to the cosmical, the all-embracing galaxy of galaxies. The universe now appeared to me as a void wherein floated rare flakes of snow, each flake a universe.

Gazing at the faintest and remotest of all the swarm of universes, I seemed, by hypertelescopic imagination, to see it as a population of suns; a

ound their dogs abandon the fold, and join the wild troops that fell upon the sheep. The black wood-dogs hunt in packs of ten or more (as many as forty have been counted), and are the pest of the farmer, for, unless his flocks are protected at night within stockades or enclosures, they are certain to be attacked. Not satisfied with killing enough to satisfy hunger, these dogs tear and mangle for sheer delight of blood, and will destroy twenty times as many as they can eat, leaving the miserably torn carcases on the field. Nor are the sheep always safe by day if the wood-dogs happen to be hungry. The shepherd is, therefore, usually accompanied by two or three mastiffs, of whose great size and strength the others stand in awe. At night, and when in large packs, starving in the snow, not even the mastiffs can check them.

No wood-dog, of any kind, has ever been known to attack man, and the hunter in the forest hears their bark in every direction without fear. It is, nevertheless, best to retire out of thei

both of these noble institutions without an instant's thought. All of you haven't a single thought for the past, for the untold billions who led the bad life as mankind slowly built up the good life for you to lead. Do you ever think of all the people who suffered and died in misery and superstition while civilization was clicking forward one more slow notch?"

"Of course I don't think about them," Brion retorted. "Why should I? I can't change the past."

"But you can change the future!" Ihjel said. "You owe something to the suffering ancestors who got you where you are today. If Scientific Humanism means anything more than just words to you, you must possess a sense of responsibility. Don't you want to try and pay off a bit of this debt by helping others who are just as backward and disease-ridden today as great-grandfather Troglodyte ever was?"

The hammering on the door was louder. This and the drug-induced buzzing in Brion's ear made thinking difficult. "Abstractly, I of course agree wi

a discussion of possible freakish curvatures in space, and of theoretical points of approach or even contact between our part of the cosmos and various other regions as distant as the farthest stars or the transgalactic gulfs themselves--or even as fabulously remote as the tentatively conceivable cosmic units beyond the whole Einsteinian space-time continuum. Gilman's handling of this theme filled everyone with admiration, even though some of his hypothetical illustrations caused an increase in the always plentiful gossip about his nervous and solitary eccentricity. What made the students shake their heads was his sober theory that a man might--given mathematical knowledge admittedly beyond all likelihood of human acquirement--step deliberately from the earth to any other celestial body which might lie at one of an infinity of specific points in the cosmic pattern.

Such a step, he said, would require only two stages; first, a passage out of the three-dimensional sphere we know, and second, a passage b