Genre Science Fiction. Page - 2

t of the "L" below them. It was perhaps six miles across; and all over the comparatively smooth surface jutted dark projections. Viewed through the glasses, they had a regular, uniform appearance.

"By Jove!" ejaculated the doctor, almost in awe. He leaned forward and scrubbed the dead-light for the tenth time. All four men strained their eyes to see.

It was the architect who broke the silence which followed. The other three were content to let the thrill of the thing have its way with them. Such a feeling had little weight with the expert in archeology.

"Well," he declared jubilantly in his boyish voice, "either I eat my hat or that's a genuine, bona fide city!"

As swiftly as an elevator drops, and as safely, the cube shot straight downward. Every second the landscape narrowed and shrunk, leaving the remaining details larger, clearer, sharper. Bit by bit the amazing thing below them resolved itself into a real metropolis.

Within five minutes they were less than a mile above

our eighth landing, all that passed. For R-14 was old again, older than any of the others.

And then, on October sixteenth, Mason opened the door of the locked cabin. It happened quite by accident. One of the arelium-thaxide conduits broke in the Marie Galante's central passageway, and the resulting explosion grounded the central feed line of the instrument equipment. In a trice the passageway was a sheet of flame, rapidly filling with smoke from burning insulation.

Norris, of course, was in the bridge cuddy with locked doors between us and him, and now with the wiring burned through there was no way of signalling him he was wanted for an emergency. In his absence Mason took command.

That passageway ran the full length of the ship. Midway down it was the door leading to the women's lounge. The explosion had jammed that door shut, and smoke was pouring forth from under the sill. All at once one of the women rushed forward to announce hysterically that Mason's wife, Estell

r a moment Bill stood over him, nostrils flaring, his whole body tense and waiting. But Tom was too groggy to get up.

"Oh, Bill, how could you!" Christy cried out, dropping to her knees beside Tom.

Bill strode with measured step to the door. There he turned, and looking back with a sneer, said, "Sweet dreams, Dream Boy!"

* * * * *

In a luxurious office of Asteroid Mining Corporation on the twenty-third floor of a Manhattan skyscraper a furious official of the corporation faced an uncomfortable underling.

"I've heard of some pretty crude tricks in my time, Heilman, but breaking into the Staker Company's office like a common house thief takes the tin medal for low grade brains!" the official ranted, pounding his desk. "I suppose you thought that was an excellent way to advance yourself in the corporation, eh? Finesse, Heilman, finesse. That's what it takes in matters like this. Asteroid Mining, before it got the monopoly, stopped competition, but not by common housebreaking--"

They walked toward a house of colored rocks.

"Miss Daphne Trilling's," said Mr. Greypoole, gesturing. "They threw it up in a day, though it's solid enough."

When they had passed an elderly woman on a bicycle, Captain Webber stopped walking.

"Mr. Greypoole, we've got to have a talk."

Mr. Greypoole shrugged and pointed and they went into an office building which was crowded with motionless men, women and children.

"Since I'm so mixed up myself," the captain said, "maybe I'd better ask--just who do you think we are?"

"I'd thought you to be the men from the Glades of course."

"I don't have the slightest idea what you're talking about. We're from the planet Earth. They were going to have another war, the 'Last War' they said, and we escaped in that rocket and started off for Mars. But something went wrong--fellow named Appleton pulled a gun, others just didn't like the Martians--we needn't go into it; they wouldn't have us so Mars didn't work out.

g, and the two mates having their hands full in driving forward the work of finishing the lading, so that the hatches might be on and things in some sort of order before the crew should be needed to make sail.

The decks everywhere were littered with the stuff put aboard from the lighter that left the brig just before I reached her, and the huddle and confusion showed that the transfer must have been made in a tearing hurry. Many of the boxes gave no hint of what was inside of them; but a good deal of the stuff--as the pigs of lead and cans of powder, the many five-gallon kegs of spirits, the boxes of fixed ammunition, the cases of arms, and so on--evidently was regular West Coast "trade." And all of it was jumbled together just as it had been tumbled aboard.

I was surprised by our starting with the brig in such a mess--until it occurred to me that the captain had no choice in the matter if he wanted to save the tide. Very likely the tide did enter into his calculations; but I was led to believe

t of the French nobility whose family had ridden the tumbrils of the Revolution, tended her fragile body and spirit with the same loving care given rare, brief-blooming flowers. You may imagine from this his attitude concerning marriage. He lived in terror of the vulgar, heavy-handed man who would one day win my mother's heart, and at last, this persistent dread killed him. His concern was unnecessary, however, for my mother chose a suitor who was as free of mundane brutality as a husband could be. Her choice was Dauphin, a remarkable white cat which strayed onto the estate shortly after his death.

Dauphin was an unusually large Angora, and his ability to speak in cultured French, English, and Italian was sufficient to cause my mother to adopt him as a household pet. It did not take long for her to realize that Dauphin deserved a higher status, and he became her friend, protector, and confidante. He never spoke of his origin, nor where he had acquired the classical education which made him such an entertaining companion. After two years, it was eas

cratching his back with it. When Philip did a doubletake, however, the ear was back to normal size and reposing on its owner's tawny cheek. Rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, he said, "Come on, Zarathustra, we're going for a walk."

He headed for the back door, Zarathustra at his heels. A double door leading off the dining room barred his way and proved to be locked. Frowning, he returned to the living room. "All right," he said to Zarathustra, "we'll go out the front way then."

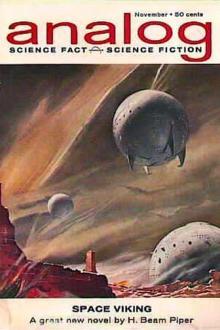

[Illustration]

He walked around the side of the house, his canine companion trotting beside him. The side yard turned out to be disappointing. It contained no roses--green ones, or any other kind. About all it did contain that was worthy of notice was a dog house--an ancient affair that was much too large for Zarathustra and which probably dated from the days when Judith had owned a larger dog. The yard itself was a mess: the grass hadn't been cut all summer, the shrubbery was ragged, and dead leaves lay everywhere

up, like you said."

Buck laughed shortly. "I'll be waiting. I don't like that lanky bastard. I reckon I got some scores to settle with him." He looked at me, and his face twisted into what he thought was a tough snarl. Funny--you could see he really wasn't tough down inside. There wasn't any hard core of confidence and strength. His toughness was in his holster, and all the rest of him was acting to match up to it.

"You know," he said, "I don't like you either, Irish. Maybe I oughta kill you. Hell, why not?"

Now, the only reason I'd stayed out of doors that afternoon was I figured Buck had already had one chance to kill me and hadn't done it, so I must be safe. That's what I figured--he had nothing against me, so I was safe. And I had an idea that maybe, when the showdown came, I might be able to help out Ben Randolph somehow--if anything on God's Earth could help him.

Now, though, I wished to hell I hadn't stayed outside. I wished I was behind one of them windows, looking

ieces, for the first time in his life, at the age of thirty-two years, Tydvil Jones swore. "No more! No more!" he said aloud, bringing his clenched fist down on the table before him, "I'm damned if I'll stand it any longer!" The trouble was, that Tydvil learned he had been robbed of his youth and the joy of living it. That the robbery was committed with pious intent, was no salve to his feelings. Affection may have misled his mother, but Amy had been an accessory, not for love, but ambition. It was not sweet to realise that he was subject for amused pity among the men he met in business. The worst of it was he felt his case was beyond remedy.

Two incidents occurred about this time that made him resolve on emancipation. In both of these he was an unwilling eavesdropper.

One night, while returning home from a meeting, he entered an empty railway compartment. At the next station, two men, well known to him, took the adjoining compartment. When he recognised their voices, he was prevented from makin

ly. Feeling despondent, I turned and walked sullenly from thelake's edge into the woodland once more, with no definite purpose inmind, only a meandering thought of my dismal situation. My thoughtsmorphed, in succession, from anxiety to despair, to anger, tofrustration, and in my frustration I knelt down and picked up a fallenbranch from the ground, walked to the nearest tree, and eyed a strange,protruding knob that stuck out from the trunk. I held the branch atshoulder's length and swung it at the knob with all the force of mybuilt up emotions. It hit with a crash and a hollow thud, leaving thebranch broken and my arm sore, but the knob undamaged.

But then something unexpected happened: with a grating noise, a smallhole appeared part way up the trunk, coming from what looked to be solidwood, for no sign was seen before of its having an opening. From thenewly opened hole was then thrust out a head, hairy and with a shortsnout-like edifice for a nose and mouth. Its eyes and the furry hairwhich