Genre Science Fiction. Page - 4

ead with an air of importance.

"Take your word for it," answered Hood without emotion, save for a slight annoyance at the other's arrogation of superior information. "'Tain't the first time there's been an earthquake since creation." And he strolled out, swinging to the doors behind him.

The night shift settled himself before the instruments with a look of dreary resignation.

"Say," he muttered aloud, "you couldn't jar that feller with a thirteen-inch bomb! He wouldn't even rub himself!"

Hood, meantime, bought an evening paper and walked slowly to the district where he lived. It was a fine night and there was no particular excitement in the streets. His wife opened the door.

"Well," she greeted him, "I'm glad you've come home at last. I was plumb scared something had happened to you. Such a shaking and rumbling and rattling I never did hear! Did you feel it?"

"I didn't feel nothin'!" answered Bill Hood. "Some one said there was a shock, that was all I heard about it.

, was as it had always been.

"'You will want to see Paris--the Paris of our time, Henri?' asked Rastin.

"'But it is different--terrible--' I said.

"'We'll take you,' Thicourt said, 'but first your clothes--'

"He got a long light coat that they had me put on, that covered my tunic and hose, and a hat of grotesque round shape that they put on my head. They led me then out of the building and into the street.

"I gazed astoundedly along that street. It had a raised walk at either side, on which many hundreds of people moved to and fro, all dressed in as strange a fashion. Many, like Rastin and Thicourt, seemed of gentle blood, yet, in spite of this, they did not wear a sword or even a dagger. There were no knights or squires, or priests or peasants. All seemed dressed much the same.

"Small lads ran to and fro selling what seemed sheets of very thin white parchment, many times folded and covered with lettering. Rastin said that these had written in them all things that had

f ever I saw honesty and truth and love and loyalty looking out of a girl's eyes, that girl is Myra McLeod."

"Thank you for that, Den," I answered simply. There was little sentiment between us. Thank heaven, there was something more.

"And so you see, you lucky dog, you'll go out to the front, and come back loaded with honours and blushes, and marry the girl of your dreams, and live happy ever after." And Dennis sighed.

"Why the sigh?" I asked. "Oh, come now," I added, suddenly remembering. "Fair exchange, you know. You haven't told me what was worrying you."

"My dear old fellow, don't be ridiculous, there's nothing worrying me."

I pressed him to no purpose. He refused to admit that he had a care in the world, and so we fell to talking of matters connected with the routine of army life, how long we should be before we got to the front, the sport we four should have in our rest time behind the trenches, our determination to stick together at all costs, etc. Suddenly Dennis sat

ay and ate heartily.

III

Retief leaned back, grateful for the lull in the music. The last of the dishes were whisked away, and more glasses filled. The exhausted entertainers stopped to pick up the thick square coins the diners threw.

Retief sighed. It had been a rare feast.

"Retief," Magnan said in the comparative quiet, "what were you saying about dog food as the music came up?"

Retief looked at him. "Haven't you noticed the pattern, Mr. Magnan? The series of deliberate affronts?"

"Deliberate affronts! Just a minute, Retief. They're uncouth, yes, crowding into doorways and that sort of thing...." He looked at Retief uncertainly.

"They herded us into a baggage warehouse at the terminal. Then they hauled us here in a garbage truck----"

"Garbage truck!"

"Only symbolic, of course. They ushered us in the tradesman's entrance, and assigned us cubicles in the servants' wing. Then we were seated with the coolie class sweepers at the bottom of the table.

o Fomalhaut V.

It was a busy two weeks for everyone involved. Captain Peter Wayne, as a central part of the team, spent much of his time planning his attack. His job would be the actual climbing of the mountain where the double-nucleus beryllium was located. It wasn't going to be an easy job; the terrain was rough, the wind, according to Jervis, whipped ragingly through the hills, and the jagged peaks thrust into the air like the teeth of some mythical dragon.

Study of the three-dimensional aerial photographs taken from the Mavis showed that the best route was probably up through one end of the valley, through a narrow pass that led around the mountain, and up the west slope, which appeared to offer better handholds and was less perpendicular than the other sides of the mountain.

This time, the expedition would have the equipment to make the climb. There were ropes, picks, and crampons, and sets of metamagnetic boots and grapples. With metamagnetic boots, Wayne thought, they'd be

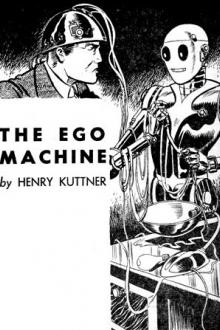

e at the desk-lamp. "F(t)--I mean, if you counted the kappa waves of my radio-atomic brain now, you'd be amazed how the frequency's increased." He paused thoughtfully. "F(t)," he added.

Moving quite slowly, like a man under water, Martin lifted his glass and drank whiskey. Then, cautiously, he looked up at the robot again.

"F(t)--" he said, paused, shuddered, and drank again. That did it. "I'm drunk," he said with an air of shaken relief. "That must be it. I was almost beginning to believe--"

"Oh, nobody believes I'm a robot at first," the robot said. "You'll notice I showed up in a movie lot, where I wouldn't arouse suspicion. I'll appear to Ivan Vasilovich in an alchemist's lab, and he'll jump to the conclusive I'm an automaton. Which, of course, I am. Then there's a Uighur on my list--I'll appear to him in a shaman's hut and he'll assume I'm a devil. A matter of ecologicologic."

"Then you're a devil?" Martin inquired, seizing on the only plaus

ow I did it, I'm sure I can teach other people. I'm no different than they are; and I don't intend to be.

She went back to the bed and sat down and began to think.

And she discovered that she could remember the greater part of everything she'd ever read.

CHAPTER IV

Calvin practiced teleportation for endless hours. He kept the metal ball Forential had given him in almost constant motion.

He would exclaim delightedly and hurl it toward one of the twenty-seven other mutants in his compartment. Until the time he hit John in the back of the head with it, his intended victims had always parried it. John lay in a pool of blood, and Calvin began to cry--loud, shrill wails of despair and contrition. When Forential came, he knew instinctively what had happened.

Calvin represented the only failure the aliens had experienced in their mutation program; ten years ago his mind had ceased to develop. But for Forential's intercession, the c

the air above and down I came again square upon my feet with a jolt that caused my teeth to rattle. And there I stood with my head and shoulders out of the water while my lungs inhaled long draughts of pure fresh air. I was too astonished to think and too weak to move, so I just stood there motionless until I had regained my equilibrium. I could never forget how sweet life seemed to me at that time. For a long time I remained standing there without giving a thought as to what I was resting upon, and when I did direct my attention to the question I was incapable of forming a satisfactory solution to the mystery. According to the charts there was no land in that part of the ocean. Could it be a whale, I wondered? The more I thought of it the more perplexed I became. The night was very dark and I could see nothing about me in any direction, so I concluded that the only thing to do was to remain standing just where I was until daybreak. It was a long and tedious wait and I suffered much from stiffness and cold,