Genre Science Fiction. Page - 6

ght. I'll say this much, though," she relented, "it will be the biggest challenge that Tom Swift Jr. and Sr. have ever faced!"

"Whew!" Bud remarked as the two boys glanced at each other. "That must mean it's plenty big news! It would have to be, skipper, to top all the other jobs you and your dad have taken on!"

Conquering outer space, probing the ocean's secrets, drilling to the earth's core--these were only a few of Tom Swift's many exciting exploits.

In his first adventure, Tom, in his Flying Lab, had gone to South America to fend off a gang of rebels seeking a valuable radioactive ore deposit. In his most recent challenge, Tom had defied the threats of Oriental killers determined to ferret out the secret of the Swifts' latest space research.

As the two boys silently recalled the exciting events of the past months, Mr. Swift returned to the living room.

Tom and Bud leaned forward in their chairs. "Well, boys," Mr. Swift said, "as I started to tell you, the space

aid. "But you better untie me. Somebody's liable to stick their nose in and get me killed."

"I'll take the chance. How do we get to the casino?"

"We follow this street. It twists around and goes under a couple tunnels. When we get to the Drunkard's Stairs we go up and it's right in front of us. A pink front with a sign like a big Luck Wheel."

"Give me your belt, Magnan," Retief said.

Magnan handed it over.

"Lie down, Illy," Retief said.

The servant looked at Retief.

"Vug and Toscin will be glad to see me," he said. "But they'll never believe me." He lay down. Retief strapped his feet together and stuffed a handkerchief in his mouth.

"Why are you doing that?" Magnan asked. "We need him."

"We know the way. And we don't need anyone to announce our arrival. It's only on three-dee that you can march a man through a gang of his pals with a finger in his back."

Magnan looked at the man. "Maybe you'd better, uh, cut his throat," he said.

Ill

n battleship and each other. Minotaur's cannons were silent. He knew it was only a matter of time before it was completely destroyed.

***

From the bridge of the Imperial carrier, INF Chimera, Fleet Admiral Zackaria watched the last minutes of Minotaur's service to the Imperium unmoved. The destruction of the enormous battleship and the tremendous loss of life brought him no sadness nor regret. He turned to his second in command and spoke to him in a strange tongue. Minotaur was lost; it was useless to them. Let it burn. If they could not have this battleship, then they would just acquire another. One that was not so fragile; one that reflected the majesty of the Imperium; one that would help them to complete the Mission.

Commodore Rissard spoke his understanding of the admiral's request and moved to comply with it. Their short exchange over, Zackaria turned back to the scene of the soon to be concluded battle and continued to watch in silence.

***

"May... M...day!" Chalmers'

shadows. As if there might be a fog. But no fog, however, thick, could hide the apple tree that grew close against the house.

But the tree was there ... shadowy, indistinct in the gray, with a few withered apples still clinging to its boughs, a few shriveled leaves reluctant to leave the parent branch.

The tree was there now. But it hadn't been when he first had looked. Mr. Chambers was sure of that.

* * * * *

And now he saw the faint outlines of his neighbor's house ... but those outlines were all wrong. They didn't jibe and fit together ... they were out of plumb. As if some giant hand had grasped the house and wrenched it out of true. Like the house he had seen across the street the night before, the house that had painfully righted itself when he thought of how it should look.

Perhaps if he thought of how his neighbor's house should look, it too might right itself. But Mr. Chambers was very weary. Too weary to think about the house.

He turned from the window and

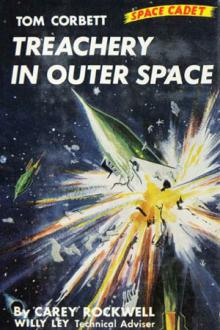

l roared. "You've got thirty seconds to make it. And if you don't make it, you'll go down on my bad-rocket list!"

Almost in one motion, the three cadet candidates saluted and charged through the door. When they had gone, Connel turned to the Polaris cadets who were still at attention. "At ease!" he roared and then grinned.

The boys came to rest and smiled back at him tentatively. They never knew what to expect from Connel. "Well, did you put them through their paces?" he asked as he jerked his thumb toward the door.

"Yes, sir!" said Tom.

"Did they know their manual? Or give you any lip when you started giving them hot rockets?" Connel referred to the hazing that was allowed by the Academy, only as another of the multitude of tests given to cadets. Cadet candidates might possibly hide dangerous flaws from Academy officials but never from boys near their own ages.

"Major," said Astro, "those fellows came close to blasting off right here in these chairs. They

of the room, their skipper's final words ringing in their ears.

Fifteen minutes later, having packed the necessary gear for the extended trip, the Polaris unit rode the slidewalk through the grassy quadrangle and the cluster of Academy buildings, out toward the spaceport. In the distance they could see the rocket cruiser Polaris, poised on the launching ramp, her long silhouette outlined sharply against the blue sky. Resting on her four stabilizer fins, her nose pointed toward the stars, the ship looked like a giant projectile poised and ready to blast its target.

"Look at her!" exclaimed Astro. "If she isn't the most beautiful ship in the universe, I'll eat my hat."

"Don't see how you could," drawled Roger, "after the way you put away Mrs. Corbett's pies!"

Tom laughed. "I'll tell you one thing, Roger," he said, pointing to the ship, "I feel like that baby is as much my home as Mom's and Dad's house back in New Chicago."

"All right, all right," said Roger.

ch it."

"If it didn't scare them off," Hudson pointed out. "The last few feet showed nothing but the inside of his throat."

Ex-ambassador Hudson looked unhappy. "I don't like the whole setup. As soon as we bring someone in, the news is sure to leak. And once the word gets out, there'll be guys lying in ambush for us--maybe even nations--scheming to steal the know-how, legally or violently. That's what scares me the most about those films I lost. Someone will find them and they may guess what it's all about, but I'm hoping they either won't believe it or can't manage to trace us."

"We could swear the hunting parties to secrecy," said Cooper.

"How could a sportsman keep still about the mounted head of a saber-tooth or a record piece of ivory?" And the same thing would apply to anyone we approached. Some university could raise dough to send a team of scientists back here and a movie company would cough up plenty to use this place as a location for a caveman epic. But it wouldn't be wo

e girl regarded Philip for a second in silence, and then quietly asked, "For the betterment of whose life after death?"

"I was speaking of those who have carried on only the forms of religion. Wrapped in the sanctity of their own small circle, they feel that their tiny souls are safe, and that they are following the example and precepts of Christ.

"The full splendor of Christ's love, the grandeur of His life and doctrine is to them a thing unknown. The infinite love, the sweet humility, the gentle charity, the subordination of self that the Master came to give a cruel, selfish and ignorant world, mean but little more to us to-day than it did to those to whom He gave it."

"And you who have chosen a military career say this," said the girl as her brother joined the pair.

To Philip her comment came as something of a shock, for he was unprepared for these words spoken with such a depth of feeling.

Gloria and Philip Dru spent most of graduation day together. He did not want to in

ll ask me for proof." He paused. "And if you could give them proof, or if this Sir Giles would let them have it, do you think they would restore it to us?"

"Will you at least try, sir?" Ali asked.

"Why, no," the Ambassador answered. "No, I do not think I will even try. It is but the word of Hajji Ibrahim here. Had he not known of the treachery of his kinsmen and come to England by the same boat as Giles Tumulty we should have known very little of what had happened, and that vaguely. But as it is, we were warned of what you call the sacrilege, and now you have talked to him, and you are convinced. But what shall I say to the Foreign Minister? No; I do not think I will try."

"You do not believe it," the Hajji said. "You do not believe that this is the Crown of Suleiman or that Allah put a mystery into it when His Permission bestowed it on the King?"

The Ambassador considered. "I have known you a long while," he said thoughtfully, "and I will tell you what I believe. I know that your