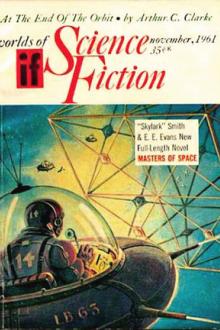

Genre Short Story. Page - 12

-glass.

"Tell Colonel Flanagan to see to it, Stephen," said the general; and thegalloper sped upon his way. The colonel, a fine old Celtic warrior, wasover at C Company in an instant.

"How are the men, Captain Foley?"

"Never better, sir," answered the senior captain, in the spirit thatmakes a Madras officer look murder if you suggest recruiting hisregiment from the Punjab.

"Stiffen them up!" cried the colonel. As he rode away a colour-sergeantseemed to trip, and fell forward into a mimosa bush. He made no effortto rise, but lay in a heap among the thorns.

"Sergeant O'Rooke's gone, sorr," cried a voice. "Never mind, lads,"said Captain Foley. "He's died like a soldier, fighting for his Queen."

"Down with the Queen!" shouted a hoarse voice from the ranks.

But the roar of the Gardner and the typewriter-like clicking of thehopper burst in at the tail of the words. Captain Foley heard them, andSubalterns Grice and Murphy heard them; but there are times when a deafear is a gift

wing-room window, suddenly saw the heavy sash give way and fall on the child's fingers. The lady fainted, I think, but at any rate the doctor was summoned, and when he had dressed the child's wounded and maimed fingers he was summoned to the mother. She was groaning with pain, and it was found that three fingers of her hand, corresponding with those that had been injured on the child's hand, were swollen and inflamed, and later, in the doctor's language, purulent sloughing set in."

Ambrose still handled delicately the green volume.

"Well, here it is," he said at last, parting with difficulty, it seemed, from his treasure.

"You will bring it back as soon as you have read it," he said, as they went out into the hall, into the old garden, faint with the odour of white lilies.

There was a broad red band in the east as Cotgrave turned to go, and from the high ground where he stood he saw that awful spectacle of London in a dream.

THE GREEN BOOK

The morocco binding of the b

Meg!"

"Good gracious me!" said Meg presently, "father's crazy. He's put the dear child's bonnet on the kettle, and hung the lid behind the door!"

Trotty hastily repaired this mistake, and went off to find some tea and a rasher of bacon he fancied "he had seen lying somewhere on the stairs."

He soon came back and made the tea, and before long they were all enjoying the meal. Trotty and Meg only took a morsel for form's sake (for they had only a very little, not enough for all), but their delight was in seeing their visitors eat, and very happy they were--though Trotty had noticed that Meg was sitting by the fire in tears when they had come in, and he feared her marriage had been broken off.

After tea Meg took Lilian to bed, and Toby showed Will Fern where he was to sleep. As he came back past Meg's door he heard the child saying her prayers, remembering Meg's name and asking for his. Then he went to sit by the fire and read his paper, and fell asleep to have a wonderful dream, so t

aid. "But you better untie me. Somebody's liable to stick their nose in and get me killed."

"I'll take the chance. How do we get to the casino?"

"We follow this street. It twists around and goes under a couple tunnels. When we get to the Drunkard's Stairs we go up and it's right in front of us. A pink front with a sign like a big Luck Wheel."

"Give me your belt, Magnan," Retief said.

Magnan handed it over.

"Lie down, Illy," Retief said.

The servant looked at Retief.

"Vug and Toscin will be glad to see me," he said. "But they'll never believe me." He lay down. Retief strapped his feet together and stuffed a handkerchief in his mouth.

"Why are you doing that?" Magnan asked. "We need him."

"We know the way. And we don't need anyone to announce our arrival. It's only on three-dee that you can march a man through a gang of his pals with a finger in his back."

Magnan looked at the man. "Maybe you'd better, uh, cut his throat," he said.

Ill

Slinkton. There he was, standing before the fire, with good large eyes and an open expression of face; but still (I thought) requiring everybody to come at him by the prepared way he offered, and by no other.

I noticed him ask my friend to introduce him to Mr. Sampson, and my friend did so. Mr. Slinkton was very happy to see me. Not too happy; there was no over-doing of the matter; happy in a thoroughly well-bred, perfectly unmeaning way.

'I thought you had met,' our host observed.

'No,' said Mr. Slinkton. 'I did look in at Mr. Sampson's office, on your recommendation; but I really did not feel justified in troubling Mr. Sampson himself, on a point in the everyday, routine of an ordinary clerk.'

I said I should have been glad to show him any attention on our friend's introduction.

'I am sure of that,' said he, 'and am much obliged. At another time, perhaps, I may be less delicate. Only, however, if I have real business; for I know, Mr. Sampson, how precious business time is,

out of sight of Dunedin. I loafed about for a couple of hours, and when the sun got well up some of the other passengers came on deck and joined me. One of them, a little perky sort of fellow, took a good long look at me, and then came over and began talking.

"Mining, I suppose?" says he.

"Yes," I says.

"Made your pile?" he asks.

"Pretty fair," says I.

"I was at it myself," he says; "I worked at the Nelson fields for three months, and spent all I made in buying a salted claim which busted up the second day. I went at it again, though, and struck it rich; but when the gold wagon was going down to the settlements, it was stuck up by those cursed rangers, and not a red cent left."

"That was a bad job," I says.

"Broke me--ruined me clean. Never mind, I've seen them all hanged for it; that makes it easier to bear. There's only one left--the villain that gave the evidence. I'd die happy if I could come across him. There are two things I have to do if I meet him."

But Johnny Chuck is lazy and does not like to go far from his own doorstep, so when Peter called the next morning Johnny refused to go, despite all Peter could say. Peter didn't waste much time arguing for he was afraid he would be late and miss something. When he reached the Green Forest he found his cousin, Jumper the Hare, and Chatterer the Red Squirrel, and Happy Jack the Gray Squirrel, already there. As soon as Peter arrived Old Mother Nature began the morning lesson.

Happy Jack," said she, "you may tell us all you know about your cousin, Chatterer."

"To begin with, he is the smallest of the Tree Squirrels," said Happy Jack. "He isn't so very much bigger than Striped Chipmunk, and that means that he is less than half as big as myself. His coat is red and his waistcoat white; his tail is about two-thirds as long as his body and flat but not very broad. Personally, I don't think it is much of a tail."

At once Chatterer's quick temper flared up and he began to scold. But Old Mother Nature silenced him and told

I had seen; and though, to satisfy my mother, we cross-questioned Fraser, it was with no result in the way of explanation. Fraser evidently knew nothing that could throw light on it, and she was quite certain that at the time I had seen the figure, both the other servants were downstairs in the kitchen. Fraser was perfectly trustworthy; we warned her not to frighten the others by speaking about the affair at all, but we could not leave off speaking about it among ourselves. We spoke about it so much for the next few days, that at last my mother lost patience, and forbade us to mention it again. At least she pretended to lose patience; in reality I believe she put a stop to the discussion because she thought it might have a bad effect on our nerves, on mine especially; for I found out afterwards that in her anxiety she even went the length of writing about it to our old doctor at home, and that it was by his advice she acted in forbidding us to talk about it any more. Poor dear mother! I don't know th

er of these. There was not even a chair, or a small table, or a bit of tin or crockery. Nothing! The jailer stood by when he ate, then took away the wooden spoon and bowl which he had used.

One by one these things sank into the brain of The Thinking Machine. When the last possibility had been considered he began an examination of his cell. From the roof, down the walls on all sides, he examined the stones and the cement between them. He stamped over the floor carefully time after time, but it was cement, perfectly solid. After the examination he sat on the edge of the iron bed and was lost in thought for a long time. For Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, The Thinking Machine, had something to think about.

He was disturbed by a rat, which ran across his foot, then scampered away into a dark corner of the cell, frightened at its own daring. After awhile The Thinking Machine, squinting steadily into the darkness of the corner where the rat had gone, was able to make out in the gloom many littl

red the anguish of my own bride's being also made a witness tothe same point, but the admiral knew where to wound me. Be still,my soul, no matter. The colonel was then brought forward with hisevidence.

It was for this point that I had saved myself up, as the turning-point of my case. Shaking myself free of my guards, - who had nobusiness to hold me, the stupids, unless I was found guilty, - Iasked the colonel what he considered the first duty of a soldier?Ere he could reply, the President of the United States rose andinformed the court, that my foe, the admiral, had suggested'Bravery,' and that prompting a witness wasn't fair. The presidentof the court immediately ordered the admiral's mouth to be filledwith leaves, and tied up with string. I had the satisfaction ofseeing the sentence carried into effect before the proceedings wentfurther.

I then took a paper from my trousers-pocket, and asked, 'What doyou consider, Col. Redford, the first duty of a soldier? Is itobedience?'

'It