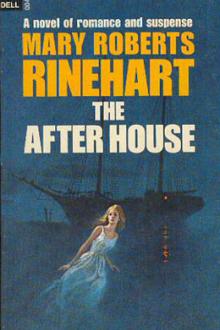

The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (color ebook reader txt) 📖

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Book online «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (color ebook reader txt) 📖». Author Mary Roberts Rinehart

The second reason was the stronger.

Singleton, the mate, had become a tractable and almost amiable prisoner. Like Turner, he was ugly only when he was drinking, and there was not even enough liquor on the Ella to revive poor Burns. He spent his days devising, with bits of wire, a ring puzzle that he intended should make his fortune. And I believe he contrived, finally, a clever enough bit of foolery. He was anxious to talk, and complained bitterly of loneliness, using every excuse to hold Tom, the cook, when he carried him his meals. He had asked for a Bible, too, and read it now and then.

The morning of Bums’s injury, I visited Singleton.

The new outrage, coming at a time when they were slowly recovering confidence, had turned the men surly. The loss of the axe, the handle of which I had told them would, under skillful eyes, reveal the murderer as accurately as a photograph, was a serious blow. Again arose the specter of the innocent suffering for the guilty. They went doggedly about their work, and wherever they gathered there was muttered talk of the white figure. There was grumbling, too, over their lack of weapons for defense.

The cook was a ringleader of the malcontents. Certain utensils were allowed him; but he was compelled at night to lock them in the galley, after either Burns’s inspection or mine, and to turn over the key to one of us.

On the morning after the attack, therefore, Tom, carrying Singleton’s breakfast to him, told him at length what had occurred in the night, and dilated on his lack of self-defense should an attack be directed toward him.

Singleton promptly offered to make him, out of wire, a key to the galley door, so that he could get what he wanted from it. The cook was to take an impression of the lock. In exchange, Tom was to fetch him, from a hiding place which Singleton designated in the forward house, a bottle of whiskey.

The cook was a shrewd mulatto, and he let Singleton make the key. It was after ten that morning when he brought it to me. I was trying to get the details of his injury from Burns, at the time, in the tent.

“I didn’t see or hear anything, Leslie,” Burns said feebly. “I don’t even remember being hit. I felt there was some one behind me. That was all.”

“There had been nothing suspicious earlier in the night?”

He lay thinking. He was still somewhat confused.

“No - I think not. Or - yes, I thought once I saw some one standing by the mainmast — behind it. It wasn’t.”

“How long was Mrs. Johns on deck?”

“Not long.”

“Did she ask you to do something for her?”

Pale as he was, he colored; but he eyed me honestly.

“Yes. Don’t ask me any more, Leslie. It had nothing to do with this.”

“What did she ask you to do?” I persisted remorselessly.

“I don’t want to talk; my head aches.”

“Very well. Then I’ll tell you what happened after I went off watch. No, I wasn’t spying. I know the woman, that’s all. She said you looked tired, and wouldn’t it be all right if you sat down for a moment and talked to her.”

“No; she said she was nervous.”

“The same thing - only better. Then she persisted in talking of the crime, and finally she said she would like to see the axe. It wouldn’t do any harm. She, wouldn’t touch it.”

He watched me uneasily.

“She didn’t either,” he said. “I’ll swear to that, Leslie. She didn’t go near the bunk. She covered her face with her hands, and leaned against the door. I thought she was going to faint.”

“Against the door, of course! And got an impression of the key. The door opens in. She could take out the key, press it against a cake of wax or even a cake of soap in her hand, and slip it back into the lock again while you - What were you doing while she was doing all that?”

“She dropped her salts. I picked them up.”

“Exactly! Well, the, axe is gone.”

He started up on his elbow.

“Gone!”

“Thrown overboard, probably. It is not in the cabin.”

It was brutal, perhaps; but the situation was all of that. As Burns fell back, colorless, Tom, the cook, brought into the tent the wire key that Singleton had made.

That morning I took from inside of Singleton’s mattress a bunch of keys, a long steel file, and the leg of one of his chairs, carefully unscrewed and wrapped at the end with wire a formidable club. One of the keys opened Singleton’s door.

That was on Saturday. Early Monday morning we sighted land.

We picked up a pilot outside the Lewes breakwater a man of few words. I told him only the outlines of our story, and I believe he half discredited me at first. God knows, I was not a creditable object. When I took him aft and showed him the jollyboat, he realized, at last, that he was face to face with a great tragedy, and paid it the tribute of throwing away his cigar.

He suggested our raising the yellow plague flag; and this we did, with a ready response from the quarantine officer. The quarantine officer came out in a power-boat, and mounted the ladder; and from that moment my command of the Ella ceased. Turner, immaculately dressed, pale, distinguished, member of the yacht club and partner in the Turner line, met him at the rail, and conducted him, with a sort of chastened affability, to the cabin.

Exhausted from lack of sleep, terrified with what had gone by and what was yet to come, unshaven and unkempt, the men gathered on the forecastle-head and waited.

The conference below lasted perhaps an hour. At the end of that time the quarantine officer came up and shouted a direction from below, as a result of which the jollyboat was cut loose, and, towed by the tug, taken to the quarantine station. There was an argument, I believe, between Turner and the officer, as to allowing us to proceed up the river without waiting for the police. Turner prevailed, however, and, from the time we hoisted the yellow flag, we were on our way to the city, a tug panting beside us, urging the broad and comfortable lines of the old cargo boat to a semblance of speed.

The quarantine officer, a dapper little man, remained on the boat, and busied himself officiously, getting the names of the men, peering at Singleton through his barred window, and expressing disappointment at my lack of foresight in having the bloodstains cleared away.

“Every stain is a clue, my man, to the trained eye,” he chirruped. “With an axe, too! What a brutal method! Brutal! Where is the axe?”

“Gone,” I said patiently. “It was stolen out of the captain’s cabin.”

He eyed me over his glasses.

“That’s very strange,” he commented. “No stains, no axe! You fellows have been mighty careful to destroy the evidence, haven’t you?”

All that long day we made our deliberate progress up the river. The luggage from the after house was carried up on deck by Adams and Clarke, and stood waiting for the customhouse.

Turner, his hands behind him, paced the deck hour by hour, his heavy face colorless. His wife, dark, repressed, with a look of being always on guard, watched him furtively. Mrs. Johns, dressed in black, talked to the doctor; and, from the notes he made, I knew she was telling the story of the tragedy. And here, there, and everywhere, efficient, normal, and so lovely that it hurt me to look at her, was Elsa. Williams, the butler, had emerged from his chrysalis of fright, and was ostentatiously looking after the family’s comfort. No clearer indication could have been given of the new status of affairs than his changed attitude toward me. He came up to me, early in the afternoon, and demanded that I wash down the deck before the women came up.

I smiled down at him cheerfully.

“Williams,” I said, “you are a coward — a mean, white-livered coward. You have skulked in the after house, behind women, when there was man’s work to do. If I wash that deck, it will be with you as a mop.”

He blustered something about speaking to Mr. Turner and seeing that I did the work I was brought on board to do, and, seeing Turner’s eye on us, finished his speech with an ugly epithet. My nerves were strained to the utmost: lack of sleep and food had done their work. I was no longer in command of the Ella; I was a common sailor, ready to vent my spleen through my fists.

I knocked him down with my open hand.

It was a barbarous and a reckless thing to do. He picked himself up and limped away, muttering. Turner had watched the scene with his cold blue eyes, and the little doctor with his near-sighted ones.

“A dangerous man, that!” said the doctor.

“Dangerous and intelligent,” replied Turner. “A bad combination!”

It was late that night when the Ella anchored in the river at Philadelphia. We were not allowed to land. The police took charge of ship, crew, and passengers. The men slept heavily on deck, except Burns, who developed a slight fever from his injury, and moved about restlessly.

It seemed to me that the vigilance of the officers was exerted largely to prevent an escape from the vessel, and not sufficiently for the safety of those on board. I spoke of this, and a guard was placed at the companionway again. Thus I saw Elsa Lee for the last time until the trial.

She was dressed, as she had been in the afternoon, in a dark cloth suit of some sort, and I did not see her until I had spoken to the officer in charge. She turned, at my voice, and called me to join her where she stood.

“We are back again, Leslie.”

“Yes, Miss Lee.”

“Back to -what? To live the whole thing over again in a courtroom! If only we could go away, anywhere, and try to forget!”

She had not expected any answer, and I had none ready. I was thinking - Heaven help me - that there were things I would not forget if I could: the lift of her lashes as she looked, up at me; the few words we had had together, the day she had told me the deck was not clean; the night I had touched her hand with my lips.

“We are to be released, I believe,” she said, “on our own - some legal term; I forget it.”

“Recognizance, probably.”

“Yes. You do not know law as well as medicine?”

“I am sorry - no; and I know very little medicine.”

“But you sewed up a wound!”

“As a matter of fact,” I admitted, “that was my initial performance, and it is badly done. It - it puckers.”

She turned on me a trifle impatiently.

“Why do you make such a secret of your identity?” she demanded. “Is it a pose? Or - have you a reason for concealing it?”

“It is not a pose; and I have nothing to be ashamed of, unless poverty -”

“Of course not. What do you mean by poverty?”

“The common garden variety sort. I have hardly a dollar in the world. As to my identity, - if it interests you at all, -, I graduated in medicine last June. I spent the last of the money that was to educate me in purchasing a dress suit to graduate in, and a supper

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Comments (0)