The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer (best novels for teenagers TXT) 📖

- Author: Sax Rohmer

- Performer: -

Book online «The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer (best novels for teenagers TXT) 📖». Author Sax Rohmer

free copyright licenses, and every other sort of contribution

you can think of. Money should be paid to ‘Project Gutenberg

Association / Carnegie-Mellon University’.

ENDTHE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93END

This etext was updated by Stewart A. Levin of Englewood, CO.

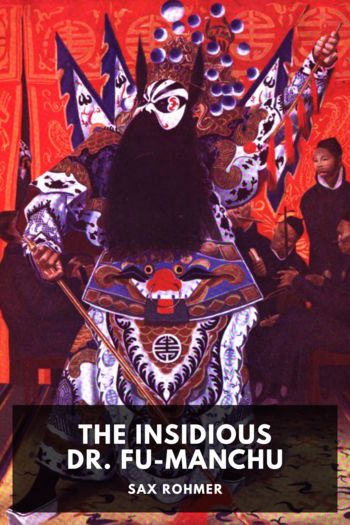

The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu

by Sax Rohmer

“A GENTLEMAN to see you, Doctor.”

From across the common a clock sounded the half-hour.

“Ten-thirty!” I said. “A late visitor. Show him up, if you please.”

I pushed my writing aside and tilted the lamp-shade, as footsteps

sounded on the landing. The next moment I had jumped to my feet,

for a tall, lean man, with his square-cut, clean-shaven face

sun-baked to the hue of coffee, entered and extended both hands,

with a cry:

“Good old Petrie! Didn’t expect me, I’ll swear!”

It was Nayland Smith—whom I had thought to be in Burma!

“Smith,” I said, and gripped his hands hard, “this is a delightful surprise!

Whatever—however—”

“Excuse me, Petrie!” he broke in. “Don’t put it down to the sun!”

And he put out the lamp, plunging the room into darkness.

I was too surprised to speak.

“No doubt you will think me mad,” he continued, and, dimly,

I could see him at the window, peering out into the road,

“but before you are many hours older you will know that I

have good reason to be cautious. Ah, nothing suspicious!

Perhaps I am first this time.” And, stepping back to the

writing-table he relighted the lamp.

“Mysterious enough for you?” he laughed, and glanced at my unfinished MS.

“A story, eh? From which I gather that the district is beastly healthy—

what, Petrie? Well, I can put some material in your way that, if sheer

uncanny mystery is a marketable commodity, ought to make you independent

of influenza and broken legs and shattered nerves and all the rest.”

I surveyed him doubtfully, but there was nothing in his appearance

to justify me in supposing him to suffer from delusions. His eyes

were too bright, certainly, and a hardness now had crept over his face.

I got out the whisky and siphon, saying:

“You have taken your leave early?”

“I am not on leave,” he replied, and slowly filled his pipe.

“I am on duty.”

“On duty!” I exclaimed. “What, are you moved to London or something?”

“I have got a roving commission, Petrie, and it doesn’t rest

with me where I am to-day nor where I shall be to-morrow.”

There was something ominous in the words, and, putting down my glass,

its contents untasted, I faced round and looked him squarely in the eyes.

“Out with it!” I said. “What is it all about?”

Smith suddenly stood up and stripped off his coat.

Rolling back his left shirt-sleeve he revealed a wicked-looking

wound in the fleshy part of the forearm. It was quite healed,

but curiously striated for an inch or so around.

“Ever seen one like it?” he asked.

“Not exactly,” I confessed. “It appears to have been deeply cauterized.”

“Right! Very deeply!” he rapped. “A barb steeped in the venom

of a hamadryad went in there!”

A shudder I could not repress ran coldly through me at mention

of that most deadly of all the reptiles of the East.

“There’s only one treatment,” he continued, rolling his sleeve down again,

“and that’s with a sharp knife, a match, and a broken cartridge.

I lay on my back, raving, for three days afterwards, in a forest that stank

with malaria, but I should have been lying there now if I had hesitated.

Here’s the point. It was not an accident!”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that it was a deliberate attempt on my life, and I am hard upon

the tracks of the man who extracted that venom—patiently, drop by drop—

from the poison-glands of the snake, who prepared that arrow, and who caused

it to be shot at me.”

“What fiend is this?”

“A fiend who, unless my calculations are at fault is now in London,

and who regularly wars with pleasant weapons of that kind. Petrie, I have

traveled from Burma not in the interests of the British Government merely,

but in the interests of the entire white race, and I honestly believe—

though I pray I may be wrong—that its survival depends largely upon

the success of my mission.”

To say that I was perplexed conveys no idea of the mental chaos

created by these extraordinary statements, for into my humdrum

suburban life Nayland Smith had brought fantasy of the wildest.

I did not know what to think, what to believe.

“I am wasting precious time!” he rapped decisively, and, draining his glass,

he stood up. “I came straight to you, because you are the only man I dare

to trust. Except the big chief at headquarters, you are the only person

in England, I hope, who knows that Nayland Smith has quitted Burma.

I must have someone with me, Petrie, all the time—it’s imperative!

Can you put me up here, and spare a few days to the strangest business,

I promise you, that ever was recorded in fact or fiction?”

I agreed readily enough, for, unfortunately, my professional

duties were not onerous.

“Good man!” he cried, wringing my hand in his impetuous way.

“We start now.”

“What, tonight?

“Tonight! I had thought of turning in, I must admit. I have not dared

to sleep for forty-eight hours, except in fifteen-minute stretches.

But there is one move that must be made tonight and immediately.

I must warn Sir Crichton Davey.”

“Sir Crichton Davey—of the India—”

“Petrie, he is a doomed man! Unless he follows my instructions

without question, without hesitation—before Heaven, nothing can

save him! I do not know when the blow will fall, how it will fall,

nor from whence, but I know that my first duty is to warn him.

Let us walk down to the corner of the common and get a taxi.”

How strangely does the adventurous intrude upon the humdrum;

for, when it intrudes at all, more often than not its intrusion

is sudden and unlooked for. To-day, we may seek for romance

and fail to find it: unsought, it lies in wait for us at most

prosaic corners of life’s highway.

The drive that night, though it divided the drably commonplace

from the wildly bizarre—though it was the bridge between the

ordinary and the outre—has left no impression upon my mind.

Into the heart of a weird mystery the cab bore me; and in reviewing

my memories of those days I wonder that the busy thoroughfares

through which we passed did not display before my eyes signs

and portents—warnings.

It was not so. I recall nothing of the route and little of import

that passed between us (we both were strangely silent, I think)

until we were come to our journey’s end. Then:

“What’s this?” muttered my friend hoarsely.

Constables were moving on a little crowd of curious idlers who pressed

about the steps of Sir Crichton Davey’s house and sought to peer in at

the open door. Without waiting for the cab to draw up to the curb,

Nayland Smith recklessly leaped out and I followed close at his heels.

“What has happened?” he demanded breathlessly of a constable.

The latter glanced at him doubtfully, but something in his voice

and bearing commanded respect.

“Sir Crichton Davey has been killed, sir.”

Smith lurched back as though he had received a physical blow, and clutched

my shoulder convulsively. Beneath the heavy tan his face had blanched,

and his eyes were set in a stare of horror.

“My God!” he whispered. “I am too late!”

With clenched fists he turned and, pressing through the group

of loungers, bounded up the steps. In the hall a man who unmistakably

was a Scotland Yard official stood talking to a footman.

Other members of the household were moving about, more or

less aimlessly, and the chilly hand of King Fear had touched

one and all, for, as they came and went, they glanced ever over

their shoulders, as if each shadow cloaked a menace, and listened,

as it seemed, for some sound which they dreaded to hear.

Smith strode up to the detective and showed him a card,

upon glancing at which the Scotland Yard man said something

in a low voice, and, nodding, touched his hat to Smith

in a respectful manner.

A few brief questions and answers, and, in gloomy silence,

we followed the detective up the heavily carpeted stair,

along a corridor lined with pictures and busts, and into a

large library. A group of people were in this room, and one,

in whom I recognized Chalmers Cleeve, of Harley Street,

was bending over a motionless form stretched upon a couch.

Another door communicated with a small study, and through

the opening I could see a man on all fours examining the carpet.

The uncomfortable sense of hush, the group about the physician,

the bizarre figure crawling, beetle-like, across the inner room,

and the grim hub, around which all this ominous activity turned,

made up a scene that etched itself indelibly on my mind.

As we entered Dr. Cleeve straightened himself, frowning thoughtfully.

“Frankly, I do not care to venture any opinion at present regarding

the immediate cause of death,” he said. “Sir Crichton was addicted

to cocaine, but there are indications which are not in accordance

with cocaine-poisoning. I fear that only a post-mortem can

establish the facts—if,” he added, “we ever arrive at them.

A most mysterious case!”

Smith stepping forward and engaging the famous pathologist in conversation,

I seized the opportunity to examine Sir Crichton’s body.

The dead man was in evening dress, but wore an old

smoking-jacket. He had been of spare but hardy build,

with thin, aquiline features, which now were oddly puffy,

as were his clenched hands. I pushed back his sleeve,

and saw the marks of the hypodermic syringe upon his left arm.

Quite mechanically I turned my attention to the right arm.

It was unscarred, but on the back of the hand was a faint

red mark, not unlike the imprint of painted lips.

I examined it closely, and even tried to rub it off, but it

evidently was caused by some morbid process of local inflammation,

if it were not a birthmark.

Turning to a pale young man whom I had understood to be Sir

Crichton’s private secretary, I drew his attention to this mark,

and inquired if it were constitutional. “It is not, sir,”

answered Dr. Cleeve, overhearing my question. “I have already

made that inquiry. Does it suggest anything to your mind?

I must confess that it affords me no assistance.”

“Nothing,” I replied. “It is most curious.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Burboyne,” said Smith, now turning to the secretary,

“but Inspector Weymouth will tell you that I act with authority.

I understand that Sir Crichton was—seized with illness in his study?”

“Yes—at half-past ten. I was working here in the library, and he inside,

as was our custom.”

“The communicating door was kept closed?”

“Yes, always. It was open for a minute or less about

ten-twenty-five, when a message came for Sir Crichton.

I took it in to him, and he then seemed in his usual health.”

“What was the message?”

“I could not say. it was brought by a district messenger, and he placed

it beside him on the table. It is there now, no doubt.”

“And at half-past ten?”

“Sir Crichton suddenly burst open the door and threw himself,

with

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Reading books romantic stories you will plunge into the world of feelings and love. Most of the time the story ends happily. Very interesting and informative to read books historical romance novels to feel the atmosphere of that time.

Comments (0)