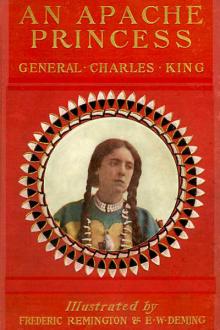

An Apache Princess by Charles King (top reads .TXT) 📖

- Author: Charles King

- Performer: -

Book online «An Apache Princess by Charles King (top reads .TXT) 📖». Author Charles King

"I can see now what we have all been puzzling over. Angela Wren might well have looked like this—four years ago."

"There is not the faintest resemblance," said Clarice, promptly rising and quitting the room.

It developed with another day that Mrs. Plume had no desire to see Miss Wren, the younger. She expressed none, indeed, when policy and the manners of good society really required it. Miss Janet had come in with Mrs. Graham and Mrs. Sanders to call upon the wife of the commanding officer and say what words of welcome were possible as appropriate to her return. "And Angela," said Janet, for reasons of her own, "will be coming later." There was no response, nor was there to the next tentative. The ladies thought Mrs. Plume should join forces with them and take Natzie out of the single cell she occupied. "Can she not be locked at the hospital, under the eye of the matron, with double sentries? It is hard to think of her barred in that hideous place with Apache prisoners and rude men all about her." But again was Mrs. Plume unresponsive. She would say no word of interest in either Angela or Natzie. At the moment when her husband was in melting mood and when a hint from her lips would have secured the partial release of the Indian girl, the hint was withheld. It would have been better for her, for her husband, for more than one brave lad on guard, had the major's wife seen fit to speak, but she would not.

So that evening brought release that, in itself, brought much relief to the commanding officer and the friends who still stood by him.

Thirty-six hours now had Natzie been a prisoner behind the bars, and no one of those we know had seen her face. At tattoo the drums and fifes began their sweet, old-fashioned soldier tunes. The guard turned out; the officer of the day buckled his belt with a sigh and started forth to inspect, just as the foremost soldiers appeared on the porch in front, buttoning their coats and adjusting their belts and slings. Half their number began to form ranks; the other half "stood by," within the main room, to pass out the prisoners, many of whom wore a clanking chain. All on a sudden there arose a wild clamor—shouts, scuffling, the thunder of iron upon resounding woodwork, hoarse orders, curses, shrieks, a yell for help, a shot, a mad scurry of many feet, furious cries of "Head 'em off!" "Shoot!" "No, no, don't shoot! You'll kill our own!" A dim cloud of ghostly, shadowy forms went tearing away down the slope toward the south. There followed a tremendous rush of troop after troop, company after company,—the whole force of Camp Sandy in uproarious pursuit,—until in the dim starlight the barren flats below the post, the willow patches along the stream, the plashing waters of the ford, the still and glassy surface of the shadowy pool, were speedily all alive with dark and darting forms intermingled in odd confusion. From the eastward side, from officers' row, Plume and his white-coated subordinates hastened to the southward face, realizing instantly what must have occurred—the long-prophesied rush of Apache prisoners for freedom. Yet how hopeless, how mad, how utterly absurd was the effort! What earthly chance had they—poor, manacled, shackled, ball-burdened wretches—to escape from two hundred fleet-footed, unhampered, stalwart young soldiery, rejoicing really in the fun and excitement of the thing? One after another the shackled fugitives were run down and overhauled, some not half across the parade, some in the shadows of the office and storehouses, some down among the shrubbery toward the lighted store, some among the shanties of Sudsville, some, lightest weighted of all, far away as the lower pool, and so one after another, the grimy, sullen, swarthy lot were slowly lugged back to the unsavory precincts wherein, for long weeks and months, they had slept or stealthily communed through the hours of the night. Three or four had been cut or slashed. Three or four soldiers had serious hurts, scratches or bruises as their fruits of the affray. But after all, the malefactors, miscreants, and incorrigibles of the Apache tribe had profited little by their wild and defiant essay—profited little, that is, if personal freedom was what they sought.

But was it? said wise heads of the garrison, as they looked the situation over. Shannon and some of his ilk were doing much independent trailing by aid of their lanterns. Taps should have been sounded at ten, but wasn't by any means, for "lights out" was the last thing to be thought of. Little by little it dawned upon Plume and his supporters that, instead of scattering, as Indian tactics demanded on all previous exploits of the kind, there had been one grand, concerted rush to the southward—planned, doubtless, for the purpose of drawing the whole garrison thither in pursuit, while three pairs of moccasined feet slipped swiftly around to the rear of the guard-house, out beyond the dim corrals, and around to a point back of "C" Troop stables, where other little hoofs had been impatiently tossing up the sands until suddenly loosed and sent bounding away to where the North Star hung low over the sheeny white mantle of San Francisco mountain. Natzie, the girl queen, was gone from the guard-house: Punch, the Lady Angela's pet pony, was gone from the corral, and who would say there had not been collusion?

"One thing is certain," said the grave-faced post commander, as, with his officers, he left the knot of troopers and troopers' wives hovering late about the guard-house, "one thing is certain; with Wren's own troopers hot on the heels of Angela's pony we'll have our Apache princess back, sure as the morning sun."

"Like hell!" said Mother Shaughnessy.

CHAPTER XXVI "WOMAN-WALK-NO-MORE"ore morning suns than could be counted in the field of the flag had come, and gone, but not a sign of Natzie. Wren's own troopers, hot on Punch's flashing heels, were cooling their own as best they could through the arid days that followed. Wren himself was now recovered sufficiently to be told of much that had been going on,—not all,—and it was Angela who constantly hovered about him, for Janet was taking a needed rest. Blakely, too, was on the mend, sitting up hours of every day and "being very lovely" in manner to all the Sanders household, for thither had he demanded to be moved even sooner than it was prudent to move him at all. Go he would, and Graham had to order it. Pat Mullins was once again "for duty." Even Todd, the bewildered victim of Natzie's knife, was stretching his legs on the hospital porch. There had come a lull in all martial proceedings at the post, and only two sensations. One of these latter was the formal investigation by the inspector general of the conditions surrounding the stabbing at Camp Sandy of Privates Mullins and Todd of the ——th U. S. Cavalry. The other was the discovery, one bright, brilliant, winter morning that Natzie's friend and savior, Angela's Punch, was back in his stall, looking every bit as saucy and "fit" as ever he did in his life. What surprised many folk in the garrison was that it surprised Angela not at all. "I thought Punch would come back," said she, in demure unconcern, and the girls at least, began to understand, and were wild to question. Only Kate Sanders, however, knew how welcome was the pet pony's coming. But what had come that was far from welcome was a coldness between Angela and Kate Sanders.

Byrne himself had arrived, and the "inquisition" had begun. No examinations under oath, no laborious recordings of question and answer, no crowd of curious listeners. The veteran inspector took each man in turn and heard his tale and jotted down his notes, and, where he thought it wise, cross-questioned over and again. One after another, Truman and Todd, Wren and Mullins, told their stories, bringing forth little that was new beyond the fact that Todd was sure it was Elise he heard that night "jabbering with Downs" on Blakely's porch. Todd felt sure that it was she who brought him whisky, and Byrne let him prattle on. It was not evidence, yet it might lead the way to light. In like manner was Mullins sure now "'Twas two ladies" stabbed him when he would have striven to stop the foremost. Byrne asked did he think they were ladies when first he set eyes on them, and Pat owned up that he thought it was some of the girls from Sudsville; it might even be Norah as one of them, coming home late from the laundresses' quarters, and trying to play him a trick. He owned to it that he grabbed the foremost, seeing at that moment no other, and thinking to win the forfeit of a kiss, and Byrne gravely assured him 'twas no shame in it, so long as Norah never found it out.

But Byrne asked Plume two questions that puzzled and worried him greatly. How much whisky had he missed? and how much opium could have been given him the night of Mrs. Plume's unconscious escapade? The major well remembered that his demijohn had grown suddenly light, and that he had found himself surprisingly heavy, dull, and drowsy. The retrospect added to his gloom and depression. Byrne had not reoccupied his old room at Plume's, now that madame and Elise were once more under the major's roof, and even in extending the customary invitation, Plume felt confident that Byrne could not and should not accept. The position he had taken with regard to Elise, her ladyship's companion and confidante, was sufficient in itself to make him, in the eyes of that lady, an unacceptable guest, but it never occurred to her, although it had to Plume, that there might be even deeper reasons. Then, too, the relations between the commander and the inspector, although each was scrupulously courteous, were now necessarily strained. Plume could not but feel that his conduct of post affairs was in a measure a matter of scrutiny. He knew that his treatment of Natzie was disapproved by nine out of ten of his command. He felt, rather than knew, that some of his people had connived at her escape, and though that escape had been a relief to everybody at Sandy, the manner of her taking off was to him a mystery and a rankling sore.

Last man to be examined was Blakely, and now indeed there was light. He had been sitting up each day for several hours; his wounds were healing well; the fever and prostration that ensued had left him weak and very thin and pale, but he had the soldier's best medicine—the consciousness of duties thoroughly and well performed. He knew that, though Wren might carry his personal antipathy to the extent of official injustice, as officers higher in rank than Wren have been known to do, the truth concerning the recent campaign must come to light, and his connection therewith be made a matter of record, as it was already a matter of fact. Wren had not yet submitted his written report. Wren and the post commander were still on terms severely official; but, to the few brother officers with whom the captain talked at all upon the stirring events through which he and his troop had so recently passed, he had made little mention of Blakely. Not so, however, the men; not so Wales Arnold, the ranchman.

Comments (0)