author - "Charles Dickens"

ch a--oh such a angel of a gentleman as Mr. Harvey'--and the other, that she 'can't tell how it is, but it don't seem a bit like a work-a-day, or a Sunday neither--it's all so unsettled and unregular.'

THE FORMAL COUPLE

The formal couple are the most prim, cold, immovable, and unsatisfactory people on the face of the earth. Their faces, voices, dress, house, furniture, walk, and manner, are all the essence of formality, unrelieved by one redeeming touch of frankness, heartiness, or nature.

Everything with the formal couple resolves itself into a matter of form. They don't call upon you on your account, but their own; not to see how you are, but to show how they are: it is not a ceremony to do honour to you, but to themselves,--not due to your position, but to theirs. If one of a friend's children die, the formal couple are as sure and punctual in sending to the house as the undertaker; if a friend's family be increased, the monthly nurse is not more attentive than they. The form

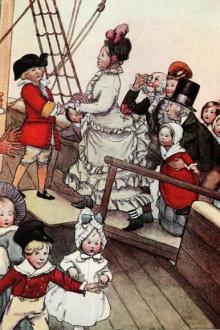

ra, surveying through his spy-glass a stranger of suspicious appearance making sail towards him. On his firing a gun ahead of her to bring her to, she ran up a flag, which he instantly recognized as the flag from the mast in the back-garden at home.

[Illustration: "Married the Chief's daughter"]

Inferring from this, that his father had put to sea to seek his long-lost son, the captain sent his own boat on board the stranger, to inquire if this was so, and if so, whether his father's intentions were strictly honourable. The boat came back with a present of greens and fresh meat, and reported that the stranger was The Family of twelve hundred tons, and had not only the captain's father on board, but also his mother, with the majority of his aunts and uncles, and all his cousins. It was further reported to Boldheart that the whole of these relations had expressed themselves in a becoming manner, and were anxious to embrace him and thank him for the glorious credit he had done them. Boldheart at onc

licia and the angelic baby.

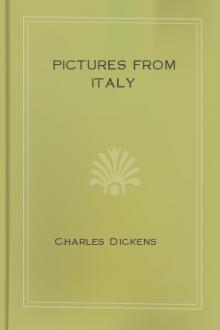

"What is the matter, Papa?"

"I am dreadfully poor, my child."

"Have you no money at all, Papa?"

[Illustration: "What is the matter, Papa?"]

"None my child."

"Is there no way left of getting any, Papa?"

"No way," said the King. "I have tried very hard, and I have tried all ways."

When she heard those last words, the Princess Alicia began to put her hand into the pocket where she kept the magic fish-bone.

"Papa," said she, "when we have tried very hard, and tried all ways, we must have done our very very best?"

"No doubt, Alicia."

"When we have done our very very best, Papa, and that is not enough, then I think the right time must have come for asking help of others." This was the very secret connected with the magic fish-bone, which she had found out for herself from the good fairy Grandmarina's words, and which she had so often whispered to her beautiful and fashionable friend the Duchess.

So she to

e ricks in farmers' yards. Out-door work was abandoned, horse-troughs at road- side inns were frozen hard, no stragglers lounged about, doors were close shut, little turnpike houses had blazing fires inside, and children (even turnpike people have children, and seem to like them) rubbed the frost from the little panes of glass with their chubby arms, that their bright eyes might catch a glimpse of the solitary coach going by. I don't know when the snow begin to set in; but I know that we were changing horses somewhere when I heard the guard remark, "That the old lady up in the sky was picking her geese pretty hard to-day." Then, indeed, I found the white down falling fast and thick.

The lonely day wore on, and I dozed it out, as a lonely traveller does. I was warm and valiant after eating and drinking,-- particularly after dinner; cold and depressed at all other times. I was always bewildered as to time and place, and always more or less out of my senses. The coach and horses seemed to execute in choru

een taught to write, by the young man without arms, who got his living with his toes (quite a writing master HE was, and taught scores in the line), but Chops would have starved to death, afore he'd have gained a bit of bread by putting his hand to a paper. This is the more curious to bear in mind, because HE had no property, nor hope of property, except his house and a sarser. When I say his house, I mean the box, painted and got up outside like a reg'lar six-roomer, that he used to creep into, with a diamond ring (or quite as good to look at) on his forefinger, and ring a little bell out of what the Public believed to be the Drawing-room winder. And when I say a sarser, I mean a Chaney sarser in which he made a collection for himself at the end of every Entertainment. His cue for that, he took from me: "Ladies and gentlemen, the little man will now walk three times round the Cairawan, and retire behind the curtain." When he said anything important, in private life, he mostly wound it up with this form of wo

As a child I was melancholy and timid, but that wasbecause the gentle consideration paid to my misfortune sunk deepinto my spirit and made me sad, even in those early days. I wasbut a very young creature when my poor mother died, and yet Iremember that often when I hung around her neck, and oftener stillwhen I played about the room before her, she would catch me to herbosom, and bursting into tears, would soothe me with every term offondness and affection. God knows I was a happy child at thosetimes, - happy to nestle in her breast, - happy to weep when shedid, - happy in not knowing why.

These occasions are so strongly impressed upon my memory, that theyseem to have occupied whole years. I had numbered very, very fewwhen they ceased for ever, but before then their meaning had beenrevealed to me.

I do not know whether all children are imbued with a quickperception of childish grace and beauty, and a strong love for it,but I was. I had no thought that I remember, either t

Courier; the whole house is at the service of my best of friends! He keeps his hand upon the carriage-door, and asks some other question to enhance the expectation. He carries a green leathern purse outside his coat, suspended by a belt. The idlers look at it; one touches it. It is full of five-franc pieces. Murmurs of admiration are heard among the boys. The landlord falls upon the Courier's neck, and folds him to his breast. He is so much fatter than he was, he says! He looks so rosy and so well!

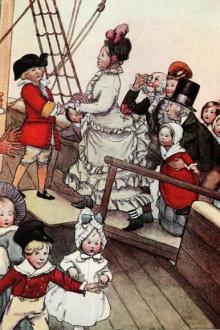

The door is opened. Breathless expectation. The lady of the family gets out. Ah sweet lady! Beautiful lady! The sister of the lady of the family gets out. Great Heaven, Ma'amselle is charming! First little boy gets out. Ah, what a beautiful little boy! First little girl gets out. Oh, but this is an enchanting child! Second little girl gets out. The landlady, yielding to the finest impulse of our common nature, catches her up in her arms! Second little boy gets out. Oh, the sweet boy! Oh, the tender little fa

For its being a little gloomy, he had hired it principally for the gardens, and he and my mistress would pass the summer weather in their shade.

'So all goes well, Baptista?' said he.

'Indubitably, signore; very well.'

We had a travelling chariot for our journey, newly built for us, and in all respects complete. All we had was complete; we wanted for nothing. The marriage took place. They were happy. I was happy, seeing all so bright, being so well situated, going to my own city, teaching my language in the rumble to the maid, la bella Carolina, whose heart was gay with laughter: who was young and rosy.

The time flew. But I observed - listen to this, I pray! (and here the courier dropped his voice) - I observed my mistress sometimes brooding in a manner very strange; in a frightened manner; in an unhappy manner; with a cloudy, uncertain alarm upon her. I think that I began to notice this when I was walking up hills by the carriage side, and master had gone on in front. At any rate

nce the Charity was founded. It being so very ill-conwenient to me as things is at present, the gentlemen are going totake off a bit of the back-yard, and make a slip of a room for 'emthere, to sit in before they go to bed."

"And then the six Poor Travellers," said I, "will be entirely out ofthe house?"

"Entirely out of the house," assented the presence, comfortablysmoothing her hands. "Which is considered much better for allparties, and much more conwenient."

I had been a little startled, in the Cathedral, by the emphasis withwhich the effigy of Master Richard Watts was bursting out of histomb; but I began to think, now, that it might be expected to comeacross the High Street some stormy night, and make a disturbancehere.

Howbeit, I kept my thoughts to myself, and accompanied the presenceto the little galleries at the back. I found them on a tiny scale,like the galleries in old inn-yards; and they were very clean.

While I was looking at them, the matron gave me to understand tha

want a word again, gentlemen - what do you call that which they give to people when it's found out, at last, that they've never been of any use, and have been paid too much for doing nothing?'

'Compensation?' suggested the vice.

'That's it,' said the chairman. 'Compensation. They didn't give it him, though, and then he got very fond of his country all at once, and went about saying that gas was a death-blow to his native land, and that it was a plot of the radicals to ruin the country and destroy the oil and cotton trade for ever, and that the whales would go and kill themselves privately, out of sheer spite and vexation at not being caught. At last he got right-down cracked; called his tobacco-pipe a gas-pipe; thought his tears were lamp- oil; and went on with all manner of nonsense of that sort, till one night he hung himself on a lamp-iron in Saint Martin's Lane, and there was an end of HIM.

'Tom loved him, gentlemen, but he survived it. He shed a tear over his grave, got very drunk,

ch a--oh such a angel of a gentleman as Mr. Harvey'--and the other, that she 'can't tell how it is, but it don't seem a bit like a work-a-day, or a Sunday neither--it's all so unsettled and unregular.'

THE FORMAL COUPLE

The formal couple are the most prim, cold, immovable, and unsatisfactory people on the face of the earth. Their faces, voices, dress, house, furniture, walk, and manner, are all the essence of formality, unrelieved by one redeeming touch of frankness, heartiness, or nature.

Everything with the formal couple resolves itself into a matter of form. They don't call upon you on your account, but their own; not to see how you are, but to show how they are: it is not a ceremony to do honour to you, but to themselves,--not due to your position, but to theirs. If one of a friend's children die, the formal couple are as sure and punctual in sending to the house as the undertaker; if a friend's family be increased, the monthly nurse is not more attentive than they. The form

ra, surveying through his spy-glass a stranger of suspicious appearance making sail towards him. On his firing a gun ahead of her to bring her to, she ran up a flag, which he instantly recognized as the flag from the mast in the back-garden at home.

[Illustration: "Married the Chief's daughter"]

Inferring from this, that his father had put to sea to seek his long-lost son, the captain sent his own boat on board the stranger, to inquire if this was so, and if so, whether his father's intentions were strictly honourable. The boat came back with a present of greens and fresh meat, and reported that the stranger was The Family of twelve hundred tons, and had not only the captain's father on board, but also his mother, with the majority of his aunts and uncles, and all his cousins. It was further reported to Boldheart that the whole of these relations had expressed themselves in a becoming manner, and were anxious to embrace him and thank him for the glorious credit he had done them. Boldheart at onc

licia and the angelic baby.

"What is the matter, Papa?"

"I am dreadfully poor, my child."

"Have you no money at all, Papa?"

[Illustration: "What is the matter, Papa?"]

"None my child."

"Is there no way left of getting any, Papa?"

"No way," said the King. "I have tried very hard, and I have tried all ways."

When she heard those last words, the Princess Alicia began to put her hand into the pocket where she kept the magic fish-bone.

"Papa," said she, "when we have tried very hard, and tried all ways, we must have done our very very best?"

"No doubt, Alicia."

"When we have done our very very best, Papa, and that is not enough, then I think the right time must have come for asking help of others." This was the very secret connected with the magic fish-bone, which she had found out for herself from the good fairy Grandmarina's words, and which she had so often whispered to her beautiful and fashionable friend the Duchess.

So she to

e ricks in farmers' yards. Out-door work was abandoned, horse-troughs at road- side inns were frozen hard, no stragglers lounged about, doors were close shut, little turnpike houses had blazing fires inside, and children (even turnpike people have children, and seem to like them) rubbed the frost from the little panes of glass with their chubby arms, that their bright eyes might catch a glimpse of the solitary coach going by. I don't know when the snow begin to set in; but I know that we were changing horses somewhere when I heard the guard remark, "That the old lady up in the sky was picking her geese pretty hard to-day." Then, indeed, I found the white down falling fast and thick.

The lonely day wore on, and I dozed it out, as a lonely traveller does. I was warm and valiant after eating and drinking,-- particularly after dinner; cold and depressed at all other times. I was always bewildered as to time and place, and always more or less out of my senses. The coach and horses seemed to execute in choru

een taught to write, by the young man without arms, who got his living with his toes (quite a writing master HE was, and taught scores in the line), but Chops would have starved to death, afore he'd have gained a bit of bread by putting his hand to a paper. This is the more curious to bear in mind, because HE had no property, nor hope of property, except his house and a sarser. When I say his house, I mean the box, painted and got up outside like a reg'lar six-roomer, that he used to creep into, with a diamond ring (or quite as good to look at) on his forefinger, and ring a little bell out of what the Public believed to be the Drawing-room winder. And when I say a sarser, I mean a Chaney sarser in which he made a collection for himself at the end of every Entertainment. His cue for that, he took from me: "Ladies and gentlemen, the little man will now walk three times round the Cairawan, and retire behind the curtain." When he said anything important, in private life, he mostly wound it up with this form of wo

As a child I was melancholy and timid, but that wasbecause the gentle consideration paid to my misfortune sunk deepinto my spirit and made me sad, even in those early days. I wasbut a very young creature when my poor mother died, and yet Iremember that often when I hung around her neck, and oftener stillwhen I played about the room before her, she would catch me to herbosom, and bursting into tears, would soothe me with every term offondness and affection. God knows I was a happy child at thosetimes, - happy to nestle in her breast, - happy to weep when shedid, - happy in not knowing why.

These occasions are so strongly impressed upon my memory, that theyseem to have occupied whole years. I had numbered very, very fewwhen they ceased for ever, but before then their meaning had beenrevealed to me.

I do not know whether all children are imbued with a quickperception of childish grace and beauty, and a strong love for it,but I was. I had no thought that I remember, either t

Courier; the whole house is at the service of my best of friends! He keeps his hand upon the carriage-door, and asks some other question to enhance the expectation. He carries a green leathern purse outside his coat, suspended by a belt. The idlers look at it; one touches it. It is full of five-franc pieces. Murmurs of admiration are heard among the boys. The landlord falls upon the Courier's neck, and folds him to his breast. He is so much fatter than he was, he says! He looks so rosy and so well!

The door is opened. Breathless expectation. The lady of the family gets out. Ah sweet lady! Beautiful lady! The sister of the lady of the family gets out. Great Heaven, Ma'amselle is charming! First little boy gets out. Ah, what a beautiful little boy! First little girl gets out. Oh, but this is an enchanting child! Second little girl gets out. The landlady, yielding to the finest impulse of our common nature, catches her up in her arms! Second little boy gets out. Oh, the sweet boy! Oh, the tender little fa

For its being a little gloomy, he had hired it principally for the gardens, and he and my mistress would pass the summer weather in their shade.

'So all goes well, Baptista?' said he.

'Indubitably, signore; very well.'

We had a travelling chariot for our journey, newly built for us, and in all respects complete. All we had was complete; we wanted for nothing. The marriage took place. They were happy. I was happy, seeing all so bright, being so well situated, going to my own city, teaching my language in the rumble to the maid, la bella Carolina, whose heart was gay with laughter: who was young and rosy.

The time flew. But I observed - listen to this, I pray! (and here the courier dropped his voice) - I observed my mistress sometimes brooding in a manner very strange; in a frightened manner; in an unhappy manner; with a cloudy, uncertain alarm upon her. I think that I began to notice this when I was walking up hills by the carriage side, and master had gone on in front. At any rate

nce the Charity was founded. It being so very ill-conwenient to me as things is at present, the gentlemen are going totake off a bit of the back-yard, and make a slip of a room for 'emthere, to sit in before they go to bed."

"And then the six Poor Travellers," said I, "will be entirely out ofthe house?"

"Entirely out of the house," assented the presence, comfortablysmoothing her hands. "Which is considered much better for allparties, and much more conwenient."

I had been a little startled, in the Cathedral, by the emphasis withwhich the effigy of Master Richard Watts was bursting out of histomb; but I began to think, now, that it might be expected to comeacross the High Street some stormy night, and make a disturbancehere.

Howbeit, I kept my thoughts to myself, and accompanied the presenceto the little galleries at the back. I found them on a tiny scale,like the galleries in old inn-yards; and they were very clean.

While I was looking at them, the matron gave me to understand tha

want a word again, gentlemen - what do you call that which they give to people when it's found out, at last, that they've never been of any use, and have been paid too much for doing nothing?'

'Compensation?' suggested the vice.

'That's it,' said the chairman. 'Compensation. They didn't give it him, though, and then he got very fond of his country all at once, and went about saying that gas was a death-blow to his native land, and that it was a plot of the radicals to ruin the country and destroy the oil and cotton trade for ever, and that the whales would go and kill themselves privately, out of sheer spite and vexation at not being caught. At last he got right-down cracked; called his tobacco-pipe a gas-pipe; thought his tears were lamp- oil; and went on with all manner of nonsense of that sort, till one night he hung himself on a lamp-iron in Saint Martin's Lane, and there was an end of HIM.

'Tom loved him, gentlemen, but he survived it. He shed a tear over his grave, got very drunk,