author - "Charles Dickens"

ine at Veneerings, expressly to meet the Member, the Engineer, the Payer-off of the National Debt, the Poem on Shakespeare, the Grievance, and the Public Office, and, dining, discovered that all of them were the most intimate friends Veneering had in the world, and that the wives of all of them (who were all there) were the objects of Mrs Veneering's most devoted affection and tender confidence.

Thus it had come about, that Mr Twemlow had said to himself in his lodgings, with his hand to his forehead: 'I must not think of this. This is enough to soften any man's brain,'--and yet was always thinking of it, and could never form a conclusion.

This evening the Veneerings give a banquet. Eleven leaves in the Twemlow; fourteen in company all told. Four pigeon-breasted retainers in plain clothes stand in line in the hall. A fifth retainer, proceeding up the staircase with a mournful air--as who should say, 'Here is another wretched creature come to dinner; such is life!'--announces, 'Mis-ter Twemlow!'

grate, 'she shall feed the birds. This big loaf is for Signor John Baptist. We must break it to get it through into the cage. So, there's a tame bird to kiss the little hand! This sausage in a vine leaf is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again--this veal in savoury jelly is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again--these three white little loaves are for Monsieur Rigaud. Again, this cheese--again, this wine--again, this tobacco--all for Monsieur Rigaud. Lucky bird!'

The child put all these things between the bars into the soft, Smooth, well-shaped hand, with evident dread--more than once drawing back her own and looking at the man with her fair brow roughened into an expression half of fright and half of anger. Whereas she had put the lump of coarse bread into the swart, scaled, knotted hands of John Baptist (who had scarcely as much nail on his eight fingers and two thumbs as would have made out one for Monsieur Rigaud), with ready confidence; and, when he kissed her hand, had herself passed it caressingly over his face. Mons

ffecting Interview between Mr. Samuel Weller and a Family Party. Mr. Pickwick makes a Tour of the diminutive World he inhabits, and resolves to mix with it, in Future, as little as possible

46. Records a touching Act of delicate Feeling not unmixed with Pleasantry, achieved and performed by Messrs. Dodson and Fogg

47. Is chiefly devoted to Matters of Business, and the temporal Advantage of Dodson and Fogg-- Mr. Winkle reappears under extraordinary Circumstances--Mr. Pickwick's Benevolence proves stronger than his Obstinacy

48. Relates how Mr. Pickwick, with the Assistance of Samuel Weller, essayed to soften the Heart of Mr. Benjamin Allen, and to mollify the Wrath of Mr. Robert Sawyer

49. Containing the Story of the Bagman's Uncle

50. How Mr. Pickwick sped upon his Mission, and how he was reinforced in the Outset by a most unexpected Auxiliary

51. In which Mr. Pickwick encounters an old Acquaintance--To which fortunate Circumstance the Reader is mainly indebted for Ma

kind. Chizzle, Mizzle, and otherwise have lapsed into a habit of vaguely promising themselves that they will look into that outstanding little matter and see what can be done for Drizzle--who was not well used--when Jarndyce and Jarndyce shall be got out of the office. Shirking and sharking in all their many varieties have been sown broadcast by the ill-fated cause; and even those who have contemplated its history from the outermost circle of such evil have been insensibly tempted into a loose way of letting bad things alone to take their own bad course, and a loose belief that if the world go wrong it was in some off-hand manner never meant to go right.

Thus, in the midst of the mud and at the heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

"Mr. Tangle," says the Lord High Chancellor, latterly something restless under the eloquence of that learned gentleman.

"Mlud," says Mr. Tangle. Mr. Tangle knows more of Jarndyce and Jarndyce than anybody. He is famous f

s forehead and face. His skin was sounwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked asthough, if he were cut, he would bleed white.

'Bitzer,' said Thomas Gradgrind. 'Your definition of a horse.'

'Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-fourgrinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in thespring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, butrequiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.'Thus (and much more) Bitzer.

'Now girl number twenty,' said Mr. Gradgrind. 'You know what ahorse is.'

She curtseyed again, and would have blushed deeper, if she couldhave blushed deeper than she had blushed all this time. Bitzer,after rapidly blinking at Thomas Gradgrind with both eyes at once,and so catching the light upon his quivering ends of lashes thatthey looked like the antennae of busy insects, put his knuckles tohis freckled forehead, and sat down again.

The third gentleman now stepped forth. A mighty man at cutting and

as that, instead of using his familiar weapons, then indeed he would have roared to lusty purpose. The owner of one scant young nose, gnawed and mumbled by the hungry cold as bones are gnawed by dogs, stooped down at Scrooge's keyhole to regale him with a Christmas carol: but at the first sound of

`God bless you, merry gentlemen! May nothing you dismay!'

Scrooge seized the ruler with such energy of action, that the singer fled in terror, leaving the keyhole to the fog and even more congenial frost.

At length the hour of shutting up the counting- house arrived. With an ill-will Scrooge dismounted from his stool, and tacitly admitted the fact to the expectant clerk in the Tank, who instantly snuffed his candle out, and put on his hat.

`You'll want all day to-morrow, I suppose?' said Scrooge.

`If quite convenient, sir.'

`It's not convenient,' said Scrooge, `and it's not fair. If I was to stop you half-a-crown for it, you'd think yourself ill-used, I'll be bound?'

rds the small hours on a Friday night.

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork jackets, I don't know; all I know is, that there was but one solitary bidding, and that was from an attorney connected with the bill-broking business, who offered two pounds in cash, and the balance in sherry, but declined to be guaranteed from drowning on any hig

Green, by one highwayman, who despoiled the illustrious creature in sight of all his retinue; prisoners in London gaols fought battles with their turnkeys, and the majesty of the law fired blunderbusses in among them, loaded with rounds of shot and ball; thieves snipped off diamond crosses from the necks of noble lords at Court drawing-rooms; musketeers went into St. Giles's, to search for contraband goods, and the mob fired on the musketeers, and the musketeers fired on the mob, and nobody thought any of these occurrences much out of the common way. In the midst of them, the hangman, ever busy and ever worse than useless, was in constant requisition; now, stringing up long rows of miscellaneous criminals; now, hanging a housebreaker on Saturday who had been taken on Tuesday; now, burning people in the hand at Newgate by the dozen, and now burning pamphlets at the door of Westminster Hall; to-day, taking the life of an atrocious murderer, and to-morrow of a wretched pilferer who had robbed a farmer's boy of s

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he camecloser to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back asfar as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfullydown into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're tobe let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to giveme a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles."He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again."Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him withboth hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keepupright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I couldattend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll,

Description

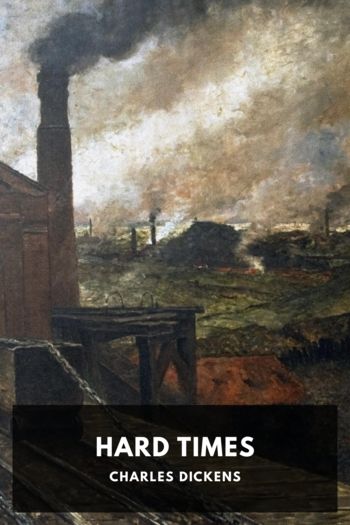

Hard Times (originally Hard Times—For These Times) was published in 1854, and is the shortest novel Charles Dickens ever published. It’s set in Coketown, a fictional mill-town set in the north of England. One of the major themes of the book is the miserable treatment of workers in the mills, and the resistance to their unionization by the mill owners, typified by the character Josiah Bounderby, who absurdly asserts that the workers live a near-idyllic life but they all “expect to be set up in a coach and six, and to be fed on turtle soup and venison, with a gold spoon.” The truth, of course, is far different.

The other major topic which Dickens tackles in this novel is the rationalist movement in schooling and the denigration of imagination and fantasy. It begins with the words “Now, what I want is, Facts,” spoken by the wealthy magnate Thomas Gradgrind, who is supervising a class at a model school he has opened. This indeed is Gradgrind’s entire philosophy. “Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else.” He is supported and encouraged in this approach by his friend Bounderby. Grandgrind raises his own children on these principles, and, as we discover, in doing so blights their lives.

The novel also follows the story of a particular mill-worker, Stephen Blackpool, who leads a tragic life. He is burdened with an alcoholic, slatternly wife, who is mostly absent from his life, but who returns at irregular intervals to trouble him. This existing marriage, and the near-impossibility of divorce for someone of his class, prevents him marrying Rachael, who is the light of his life. Dickens depicts Stephen as representing the nobility of honest work, and contrasts his character with that of the self-satisfied humbug Josiah Bounderby who represents the worst aspects of capitalism.

ine at Veneerings, expressly to meet the Member, the Engineer, the Payer-off of the National Debt, the Poem on Shakespeare, the Grievance, and the Public Office, and, dining, discovered that all of them were the most intimate friends Veneering had in the world, and that the wives of all of them (who were all there) were the objects of Mrs Veneering's most devoted affection and tender confidence.

Thus it had come about, that Mr Twemlow had said to himself in his lodgings, with his hand to his forehead: 'I must not think of this. This is enough to soften any man's brain,'--and yet was always thinking of it, and could never form a conclusion.

This evening the Veneerings give a banquet. Eleven leaves in the Twemlow; fourteen in company all told. Four pigeon-breasted retainers in plain clothes stand in line in the hall. A fifth retainer, proceeding up the staircase with a mournful air--as who should say, 'Here is another wretched creature come to dinner; such is life!'--announces, 'Mis-ter Twemlow!'

grate, 'she shall feed the birds. This big loaf is for Signor John Baptist. We must break it to get it through into the cage. So, there's a tame bird to kiss the little hand! This sausage in a vine leaf is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again--this veal in savoury jelly is for Monsieur Rigaud. Again--these three white little loaves are for Monsieur Rigaud. Again, this cheese--again, this wine--again, this tobacco--all for Monsieur Rigaud. Lucky bird!'

The child put all these things between the bars into the soft, Smooth, well-shaped hand, with evident dread--more than once drawing back her own and looking at the man with her fair brow roughened into an expression half of fright and half of anger. Whereas she had put the lump of coarse bread into the swart, scaled, knotted hands of John Baptist (who had scarcely as much nail on his eight fingers and two thumbs as would have made out one for Monsieur Rigaud), with ready confidence; and, when he kissed her hand, had herself passed it caressingly over his face. Mons

ffecting Interview between Mr. Samuel Weller and a Family Party. Mr. Pickwick makes a Tour of the diminutive World he inhabits, and resolves to mix with it, in Future, as little as possible

46. Records a touching Act of delicate Feeling not unmixed with Pleasantry, achieved and performed by Messrs. Dodson and Fogg

47. Is chiefly devoted to Matters of Business, and the temporal Advantage of Dodson and Fogg-- Mr. Winkle reappears under extraordinary Circumstances--Mr. Pickwick's Benevolence proves stronger than his Obstinacy

48. Relates how Mr. Pickwick, with the Assistance of Samuel Weller, essayed to soften the Heart of Mr. Benjamin Allen, and to mollify the Wrath of Mr. Robert Sawyer

49. Containing the Story of the Bagman's Uncle

50. How Mr. Pickwick sped upon his Mission, and how he was reinforced in the Outset by a most unexpected Auxiliary

51. In which Mr. Pickwick encounters an old Acquaintance--To which fortunate Circumstance the Reader is mainly indebted for Ma

kind. Chizzle, Mizzle, and otherwise have lapsed into a habit of vaguely promising themselves that they will look into that outstanding little matter and see what can be done for Drizzle--who was not well used--when Jarndyce and Jarndyce shall be got out of the office. Shirking and sharking in all their many varieties have been sown broadcast by the ill-fated cause; and even those who have contemplated its history from the outermost circle of such evil have been insensibly tempted into a loose way of letting bad things alone to take their own bad course, and a loose belief that if the world go wrong it was in some off-hand manner never meant to go right.

Thus, in the midst of the mud and at the heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

"Mr. Tangle," says the Lord High Chancellor, latterly something restless under the eloquence of that learned gentleman.

"Mlud," says Mr. Tangle. Mr. Tangle knows more of Jarndyce and Jarndyce than anybody. He is famous f

s forehead and face. His skin was sounwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked asthough, if he were cut, he would bleed white.

'Bitzer,' said Thomas Gradgrind. 'Your definition of a horse.'

'Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-fourgrinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in thespring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, butrequiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.'Thus (and much more) Bitzer.

'Now girl number twenty,' said Mr. Gradgrind. 'You know what ahorse is.'

She curtseyed again, and would have blushed deeper, if she couldhave blushed deeper than she had blushed all this time. Bitzer,after rapidly blinking at Thomas Gradgrind with both eyes at once,and so catching the light upon his quivering ends of lashes thatthey looked like the antennae of busy insects, put his knuckles tohis freckled forehead, and sat down again.

The third gentleman now stepped forth. A mighty man at cutting and

as that, instead of using his familiar weapons, then indeed he would have roared to lusty purpose. The owner of one scant young nose, gnawed and mumbled by the hungry cold as bones are gnawed by dogs, stooped down at Scrooge's keyhole to regale him with a Christmas carol: but at the first sound of

`God bless you, merry gentlemen! May nothing you dismay!'

Scrooge seized the ruler with such energy of action, that the singer fled in terror, leaving the keyhole to the fog and even more congenial frost.

At length the hour of shutting up the counting- house arrived. With an ill-will Scrooge dismounted from his stool, and tacitly admitted the fact to the expectant clerk in the Tank, who instantly snuffed his candle out, and put on his hat.

`You'll want all day to-morrow, I suppose?' said Scrooge.

`If quite convenient, sir.'

`It's not convenient,' said Scrooge, `and it's not fair. If I was to stop you half-a-crown for it, you'd think yourself ill-used, I'll be bound?'

rds the small hours on a Friday night.

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork jackets, I don't know; all I know is, that there was but one solitary bidding, and that was from an attorney connected with the bill-broking business, who offered two pounds in cash, and the balance in sherry, but declined to be guaranteed from drowning on any hig

Green, by one highwayman, who despoiled the illustrious creature in sight of all his retinue; prisoners in London gaols fought battles with their turnkeys, and the majesty of the law fired blunderbusses in among them, loaded with rounds of shot and ball; thieves snipped off diamond crosses from the necks of noble lords at Court drawing-rooms; musketeers went into St. Giles's, to search for contraband goods, and the mob fired on the musketeers, and the musketeers fired on the mob, and nobody thought any of these occurrences much out of the common way. In the midst of them, the hangman, ever busy and ever worse than useless, was in constant requisition; now, stringing up long rows of miscellaneous criminals; now, hanging a housebreaker on Saturday who had been taken on Tuesday; now, burning people in the hand at Newgate by the dozen, and now burning pamphlets at the door of Westminster Hall; to-day, taking the life of an atrocious murderer, and to-morrow of a wretched pilferer who had robbed a farmer's boy of s

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he camecloser to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back asfar as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfullydown into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're tobe let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to giveme a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles."He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again."Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him withboth hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keepupright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I couldattend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll,

Description

Hard Times (originally Hard Times—For These Times) was published in 1854, and is the shortest novel Charles Dickens ever published. It’s set in Coketown, a fictional mill-town set in the north of England. One of the major themes of the book is the miserable treatment of workers in the mills, and the resistance to their unionization by the mill owners, typified by the character Josiah Bounderby, who absurdly asserts that the workers live a near-idyllic life but they all “expect to be set up in a coach and six, and to be fed on turtle soup and venison, with a gold spoon.” The truth, of course, is far different.

The other major topic which Dickens tackles in this novel is the rationalist movement in schooling and the denigration of imagination and fantasy. It begins with the words “Now, what I want is, Facts,” spoken by the wealthy magnate Thomas Gradgrind, who is supervising a class at a model school he has opened. This indeed is Gradgrind’s entire philosophy. “Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else.” He is supported and encouraged in this approach by his friend Bounderby. Grandgrind raises his own children on these principles, and, as we discover, in doing so blights their lives.

The novel also follows the story of a particular mill-worker, Stephen Blackpool, who leads a tragic life. He is burdened with an alcoholic, slatternly wife, who is mostly absent from his life, but who returns at irregular intervals to trouble him. This existing marriage, and the near-impossibility of divorce for someone of his class, prevents him marrying Rachael, who is the light of his life. Dickens depicts Stephen as representing the nobility of honest work, and contrasts his character with that of the self-satisfied humbug Josiah Bounderby who represents the worst aspects of capitalism.