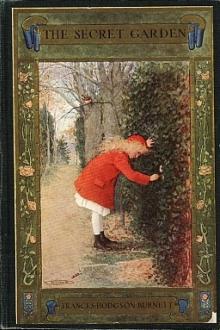

author - "Frances Hodgson Burnett"

Description

Mary’s parents fall ill and die, forcing her to be transplanted from India to the English countryside. She arrives at a strange and foreign country manor, where she discovers a long-neglected garden and hears strange sobbing noises at night.

Thus begins The Secret Garden, a children’s book with an unusually dense collection of themes, symbols, and motifs. Mary’s personal development mirrors her unraveling the secret of the hidden garden, and a subtle backdrop of magical realism adds a mysterious air to the proceedings.

Contemporary reception left The Secret Garden largely unnoticed, eclipsed by Hodgson’s other work, Little Lord Fauntleroy. Since then, however, the book’s reputation has steadily grown, with modern critics considering it one of the finest children’s books of the 20th century.

ed great, heavy childish sobs, shedid not dare to strike him, and raged the more.

If it were known that she had harbored him, the priests would be uponher, and all that she had would be taken from her and burned. She wouldnot even let him put his clothes on in her house.

"Take thy rags and begone in thy nakedness! Clothe thyself on thehillside! Let none see thee until thou art far away! Rot as thou wilt,but dare not to name me! Begone! begone! begone!"

And with his rags he fled naked through the doorway, and hid himself inthe little wood beyond.

Later, as he went on his way, he had hidden himself in the daytimebehind bushes by the wayside or off the road; he had crouched behindrocks and boulders; he had slept in caves when he had found them; he hadshrunk away from all human sight. He knew it could not be long before hewould be discovered, and then he would be shut up; and afterward hewould be as Berias until he died alone. Like unto Berias! To him itseemed as though surely never child

e minutes.

But there had been a clever, good-natured littleFrench teacher who had said to the music-master:

"Zat leetle Crewe. Vat a child! A so ogly beauty!Ze so large eyes! ze so little spirituelle face.Waid till she grow up. You shall see!"

This morning, however, in the tight, smallblack frock, she looked thinner and odder thanever, and her eyes were fixed on Miss Minchinwith a queer steadiness as she slowly advancedinto the parlor, clutching her doll.

"Put your doll down!" said Miss Minchin.

"No," said the child, I won't put her down;I want her with me. She is all I have. She hasstayed with me all the time since my papa died."

She had never been an obedient child. She hadhad her own way ever since she was born, and therewas about her an air of silent determination underwhich Miss Minchin had always felt secretly uncomfortable.And that lady felt even now that perhaps it would beas well not to insist on her point. So she lookedat her as severely as possible.

"Yo

nies in window-sashes into the room. "Someoneis wrong. Is it I--or You?"

His thin lips drew themselvesback against his teeth in a mirthlesssmile which was like a grin.

"Yes," he said. "I am prettyfar gone. I am beginning to talk tomyself about God. Bryan did it justbefore he was taken to Dr. Hewletts'place and cut his throat."

He had not led a specially evillife; he had not broken laws, butthe subject of Deity was not onewhich his scheme of existence hadincluded. When it had hauntedhim of late he had felt it an untowardand morbid sign. The thinghad drawn him--drawn him; hehad complained against it, he hadargued, sometimes he knew--shuddering--that he had raved. Somethinghad seemed to stand aside andwatch his being and his thinking.Something which filled the universehad seemed to wait, and to havewaited through all the eternal ages,to see what he--one man--woulddo. At times a great appalled wonderhad swept over him at his realizationthat he had never known orthoug

House of Coombe who asked the first question about her.

"What will you DO with her?" he inquired detachedly.

The frequently referred to "babe unborn" could not have presented a gaze of purer innocence than did the lovely Feather. Her eyes of larkspur blueness were clear of any thought or intention as spring water is clear at its unclouded best.

Her ripple of a laugh was clear also--enchantingly clear.

"Do!" repeated. "What is it people 'do' with babies? I suppose the nurse knows. I don't. I wouldn't touch her for the world. She frightens me."

She floated a trifle nearer and bent to look at her.

"I shall call her Robin," she said. "Her name is really Roberta as she couldn't be called Robert. People will turn round to look at a girl when they hear her called Robin. Besides she has eyes like a robin. I wish she'd open them and let you see."

By chance she did open them at the moment--quite slowly. They were dark liquid brown and seemed to be all lustrous iris which

tion.

This was because of the promises he had made to his father, andthey had been the first thing he remembered. Not that he hadever regretted anything connected with his father. He threw hisblack head up as he thought of that. None of the other boys hadsuch a father, not one of them. His father was his idol and hischief. He had scarcely ever seen him when his clothes had notbeen poor and shabby, but he had also never seen him when,despite his worn coat and frayed linen, he had not stood outamong all others as more distinguished than the most noticeableof them. When he walked down a street, people turned to look athim even oftener than they turned to look at Marco, and the boyfelt as if it was not merely because he was a big man with ahandsome, dark face, but because he looked, somehow, as if he hadbeen born to command armies, and as if no one would think ofdisobeying him. Yet Marco had never seen him command any one,and they had always been poor, and shabbily dressed, and oftenenou

te Manor, she looked so stony and stubbornly uninterestedthat they did not know what to think about her. They tried to be kind toher, but she only turned her face away when Mrs. Crawford attempted tokiss her, and held herself stiffly when Mr. Crawford patted hershoulder.

"She is such a plain child," Mrs. Crawford said pityingly, afterward."And her mother was such a pretty creature. She had a very prettymanner, too, and Mary has the most unattractive ways I ever saw in achild. The children call her 'Mistress Mary Quite Contrary,' and thoughit's naughty of them, one can't help understanding it."

"Perhaps if her mother had carried her pretty face and her prettymanners oftener into the nursery Mary might have learned some prettyways too. It is very sad, now the poor beautiful thing is gone, toremember that many people never even knew that she had a child at all."

"I believe she scarcely ever looked at her," sighed Mrs. Crawford."When her Ayah was dead there was no one to give a thought to the

ay from it--generally to England and toschool. She had seen other children go away, and had heard theirfathers and mothers talk about the letters they received fromthem. She had known that she would be obliged to go also, andthough sometimes her father's stories of the voyage and the newcountry had attracted her, she had been troubled by the thoughtthat he could not stay with her.

"Couldn't you go to that place with me, papa?" she had asked whenshe was five years old. "Couldn't you go to school, too? Iwould help you with your lessons."

"But you will not have to stay for a very long time, littleSara," he had always said. "You will go to a nice house wherethere will be a lot of little girls, and you will play together,and I will send you plenty of books, and you will grow so fastthat it will seem scarcely a year before you are big enough andclever enough to come back and take care of papa."

She had liked to think of that. To keep the house for herfather; to ride with him, and sit at th

Description

Mary’s parents fall ill and die, forcing her to be transplanted from India to the English countryside. She arrives at a strange and foreign country manor, where she discovers a long-neglected garden and hears strange sobbing noises at night.

Thus begins The Secret Garden, a children’s book with an unusually dense collection of themes, symbols, and motifs. Mary’s personal development mirrors her unraveling the secret of the hidden garden, and a subtle backdrop of magical realism adds a mysterious air to the proceedings.

Contemporary reception left The Secret Garden largely unnoticed, eclipsed by Hodgson’s other work, Little Lord Fauntleroy. Since then, however, the book’s reputation has steadily grown, with modern critics considering it one of the finest children’s books of the 20th century.

ed great, heavy childish sobs, shedid not dare to strike him, and raged the more.

If it were known that she had harbored him, the priests would be uponher, and all that she had would be taken from her and burned. She wouldnot even let him put his clothes on in her house.

"Take thy rags and begone in thy nakedness! Clothe thyself on thehillside! Let none see thee until thou art far away! Rot as thou wilt,but dare not to name me! Begone! begone! begone!"

And with his rags he fled naked through the doorway, and hid himself inthe little wood beyond.

Later, as he went on his way, he had hidden himself in the daytimebehind bushes by the wayside or off the road; he had crouched behindrocks and boulders; he had slept in caves when he had found them; he hadshrunk away from all human sight. He knew it could not be long before hewould be discovered, and then he would be shut up; and afterward hewould be as Berias until he died alone. Like unto Berias! To him itseemed as though surely never child

e minutes.

But there had been a clever, good-natured littleFrench teacher who had said to the music-master:

"Zat leetle Crewe. Vat a child! A so ogly beauty!Ze so large eyes! ze so little spirituelle face.Waid till she grow up. You shall see!"

This morning, however, in the tight, smallblack frock, she looked thinner and odder thanever, and her eyes were fixed on Miss Minchinwith a queer steadiness as she slowly advancedinto the parlor, clutching her doll.

"Put your doll down!" said Miss Minchin.

"No," said the child, I won't put her down;I want her with me. She is all I have. She hasstayed with me all the time since my papa died."

She had never been an obedient child. She hadhad her own way ever since she was born, and therewas about her an air of silent determination underwhich Miss Minchin had always felt secretly uncomfortable.And that lady felt even now that perhaps it would beas well not to insist on her point. So she lookedat her as severely as possible.

"Yo

nies in window-sashes into the room. "Someoneis wrong. Is it I--or You?"

His thin lips drew themselvesback against his teeth in a mirthlesssmile which was like a grin.

"Yes," he said. "I am prettyfar gone. I am beginning to talk tomyself about God. Bryan did it justbefore he was taken to Dr. Hewletts'place and cut his throat."

He had not led a specially evillife; he had not broken laws, butthe subject of Deity was not onewhich his scheme of existence hadincluded. When it had hauntedhim of late he had felt it an untowardand morbid sign. The thinghad drawn him--drawn him; hehad complained against it, he hadargued, sometimes he knew--shuddering--that he had raved. Somethinghad seemed to stand aside andwatch his being and his thinking.Something which filled the universehad seemed to wait, and to havewaited through all the eternal ages,to see what he--one man--woulddo. At times a great appalled wonderhad swept over him at his realizationthat he had never known orthoug

House of Coombe who asked the first question about her.

"What will you DO with her?" he inquired detachedly.

The frequently referred to "babe unborn" could not have presented a gaze of purer innocence than did the lovely Feather. Her eyes of larkspur blueness were clear of any thought or intention as spring water is clear at its unclouded best.

Her ripple of a laugh was clear also--enchantingly clear.

"Do!" repeated. "What is it people 'do' with babies? I suppose the nurse knows. I don't. I wouldn't touch her for the world. She frightens me."

She floated a trifle nearer and bent to look at her.

"I shall call her Robin," she said. "Her name is really Roberta as she couldn't be called Robert. People will turn round to look at a girl when they hear her called Robin. Besides she has eyes like a robin. I wish she'd open them and let you see."

By chance she did open them at the moment--quite slowly. They were dark liquid brown and seemed to be all lustrous iris which

tion.

This was because of the promises he had made to his father, andthey had been the first thing he remembered. Not that he hadever regretted anything connected with his father. He threw hisblack head up as he thought of that. None of the other boys hadsuch a father, not one of them. His father was his idol and hischief. He had scarcely ever seen him when his clothes had notbeen poor and shabby, but he had also never seen him when,despite his worn coat and frayed linen, he had not stood outamong all others as more distinguished than the most noticeableof them. When he walked down a street, people turned to look athim even oftener than they turned to look at Marco, and the boyfelt as if it was not merely because he was a big man with ahandsome, dark face, but because he looked, somehow, as if he hadbeen born to command armies, and as if no one would think ofdisobeying him. Yet Marco had never seen him command any one,and they had always been poor, and shabbily dressed, and oftenenou

te Manor, she looked so stony and stubbornly uninterestedthat they did not know what to think about her. They tried to be kind toher, but she only turned her face away when Mrs. Crawford attempted tokiss her, and held herself stiffly when Mr. Crawford patted hershoulder.

"She is such a plain child," Mrs. Crawford said pityingly, afterward."And her mother was such a pretty creature. She had a very prettymanner, too, and Mary has the most unattractive ways I ever saw in achild. The children call her 'Mistress Mary Quite Contrary,' and thoughit's naughty of them, one can't help understanding it."

"Perhaps if her mother had carried her pretty face and her prettymanners oftener into the nursery Mary might have learned some prettyways too. It is very sad, now the poor beautiful thing is gone, toremember that many people never even knew that she had a child at all."

"I believe she scarcely ever looked at her," sighed Mrs. Crawford."When her Ayah was dead there was no one to give a thought to the

ay from it--generally to England and toschool. She had seen other children go away, and had heard theirfathers and mothers talk about the letters they received fromthem. She had known that she would be obliged to go also, andthough sometimes her father's stories of the voyage and the newcountry had attracted her, she had been troubled by the thoughtthat he could not stay with her.

"Couldn't you go to that place with me, papa?" she had asked whenshe was five years old. "Couldn't you go to school, too? Iwould help you with your lessons."

"But you will not have to stay for a very long time, littleSara," he had always said. "You will go to a nice house wherethere will be a lot of little girls, and you will play together,and I will send you plenty of books, and you will grow so fastthat it will seem scarcely a year before you are big enough andclever enough to come back and take care of papa."

She had liked to think of that. To keep the house for herfather; to ride with him, and sit at th