have also been concerned not to leave out of accountChina's relations with her neighbours. Now that we have a betterknowledge of China's neighbours, the Turks, Mongols, Tibetans, Tunguses,Tai, not confined to the narratives of Chinese, who always speak only of"barbarians", we are better able to realize how closely China has beenassociated with her neighbours from the first day of her history to thepresent time; how greatly she is indebted to them, and how much she hasgiven them. We no longer see China as a great civilization surrounded bybarbarians, but we study the Chinese coming to terms with theirneighbours, who had civilizations of quite different types butnevertheless developed ones.

It is usual to split up Chinese history under the various dynasties thathave ruled China or parts thereof. The beginning or end of a dynastydoes not always indicate the beginning or the end of a definite periodof China's social or cultural development. We have tried to breakChina's history down into the thre

rt and learning, pleasure, sense,

To glean eidolons.

Put in thy chants said he,

No more the puzzling hour nor day, nor segments, parts, put in,Put first before the rest as light for all and entrance-song of all,

That of eidolons.

Ever the dim beginning,

Ever the growth, the rounding of the circle,

Ever the summit and the merge at last, (to surely start again,)

Eidolons! eidolons!

Ever the mutable,

Ever materials, changing, crumbling, re-cohering,

Ever the ateliers, the factories divine,

Issuing eidolons.

Lo, I or you,

Or woman, man, or state, known or unknown,

We seeming solid wealth, strength, beauty build,

But really build eidolons.

The ostent evanescent,

The substance of an artist's mood or savan's studies long,

Or warrior's, martyr's, hero's toils,

To fashion his eidolon.

Of every human life,

(The units gather'd, posted, not a thought, emotion, deed, le

eateningly, and offhe went again. "Mumps one pound, that is what I have put down,but I daresay it will be more like thirty shillings -- don'tspeak -- measles one five, German measles half a guinea, makestwo fifteen six -- don't waggle your finger -- whooping-cough,say fifteen shillings" -- and so on it went, and it added updifferently each time; but at last Wendy just got through,with mumps reduced to twelve six, and the two kinds of measlestreated as one.

There was the same excitement over John, and Michael had even anarrower squeak; but both were kept, and soon, you might have seenthe three of them going in a row to Miss Fulsom's Kindergartenschool, accompanied by their nurse.

Mrs. Darling loved to have everything just so, and Mr. Darlinghad a passion for being exactly like his neighbours; so, ofcourse, they had a nurse. As they were poor, owing to the amountof milk the children drank, this nurse was a prim Newfoundlanddog, called Nana, who had belonged to no one in particular un

s that there is some mischief afoot."

"If you said 'hope' instead of 'fear,' it would be nearer the truth, I'm thinking, Mr. Holmes," the inspector answered, with a knowing grin. "Well, maybe a wee nip would keep out the raw morning chill. No, I won't smoke, I thank you. I'll have to be pushing on my way; for the early hours of a case are the precious ones, as no man knows better than your own self. But--but--"

The inspector had stopped suddenly, and was staring with a look of absolute amazement at a paper upon the table. It was the sheet upon which I had scrawled the enigmatic message.

"Douglas!" he stammered. "Birlstone! What's this, Mr. Holmes? Man, it's witchcraft! Where in the name of all that is wonderful did you get those names?"

"It is a cipher that Dr. Watson and I have had occasion to solve. But why--what's amiss with the names?"

The inspector looked from one to the other of us in dazed astonishment. "Just this," said he, "that Mr. Douglas of Birlstone Manor House

That night, when supper was finished and they sat on the oblong box and pulled at their pipes, the circle of gleaming eyes drew in even closer than before.

"I wisht they'd spring up a bunch of moose or something, an' go away an' leave us alone," Bill said.

Henry grunted with an intonation that was not all sympathy, and for a quarter of an hour they sat on in silence, Henry staring at the fire, and Bill at the circle of eyes that burned in the darkness just beyond the firelight.

"I wisht we was pullin' into McGurry right now," he began again.

"Shut up your wishin' and your croakin'," Henry burst out angrily. "Your stomach's sour. That's what's ailin' you. Swallow a spoonful of sody, an' you'll sweeten up wonderful an' be more pleasant company."

In the morning Henry was aroused by fervid blasphemy that proceeded from the mouth of Bill. Henry propped himself up on an elbow and looked to see his comrade standing among the dogs beside the replenished fire, his a

y give them occasionally will be of far greater assistance than a yearly allowance, because they would only enlarge their style of living if they felt sure of a larger income, and would not be sixpence the richer for it at the end of the year. It will certainly be much the best way. A present of fifty pounds, now and then, will prevent their ever being distressed for money, and will, I think, be amply discharging my promise to my father."

"To be sure it will. Indeed, to say the truth, I am convinced within myself that your father had no idea of your giving them any money at all. The assistance he thought of, I dare say, was only such as might be reasonably expected of you; for instance, such as looking out for a comfortable small house for them, helping them to move their things, and sending them presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season. I'll lay my life that he meant nothing farther; indeed, it would be very strange and unreasonable if he did. Do but consider, my dear Mr. D

're good, you're good.

Chapter Two

I came out of the bathroom with 30 seconds left on the ticker, and started walking briskly towards the conference room. Miranda was trotting immediately behind.

"What's the meeting about?" I asked, nodding to Drew Roberts as I passed his office.

"He didn't say," Miranda said.

"Do we know who else is in the meeting?"

"He didn't say," Miranda said.

The second-floor conference room sits adjacent to Carl's office, which is at the smaller end of our agency's vaguely egg-shaped building. The building itself has been written up in Architectural Digest, which described it as a "Four-way collision between Frank Gehry, Le Corbousier, Jay Ward and the salmonella bacteria." It's unfair to the salmonella bacteria. My office is stacked on the larger arc of the egg on the first floor, along with the offices of all the other junior agents. After today, a second-floor, little-arc office was

ting that all philosophers, in so far as they have beendogmatists, have failed to understand women--that the terribleseriousness and clumsy importunity with which they have usuallypaid their addresses to Truth, have been unskilled and unseemlymethods for winning a woman? Certainly she has never allowedherself to be won; and at present every kind of dogma stands withsad and discouraged mien--IF, indeed, it stands at all! For thereare scoffers who maintain that it has fallen, that all dogma lieson the ground--nay more, that it is at its last gasp. But tospeak seriously, there are good grounds for hoping that alldogmatizing in philosophy, whatever solemn, whatever conclusiveand decided airs it has assumed, may have been only a noblepuerilism and tyronism; and probably the time is at hand when itwill be once and again understood WHAT has actually sufficed forthe basis of such imposing and absolute philosophical edifices asthe dogmatists have hitherto reared: perhaps some popularsuperstition of imm

the summer with unimpaired cheerfulness, confiding to me that he secured his luncheons free at the soda counter. He came frequently to see me, bringing always a pocketful of chewing gum, which he assured me was excellent to allay the gnawings of hunger, and later, as my condition warranted it, small bags of gum-drops and other pharmacy confections.

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

ch of delicate pink dust in the hole. Iput my finger in, to feel it, and said OUCH! and took it out again. Itwas a cruel pain. I put my finger in my mouth; and by standing first onone foot and then the other, and grunting, I presently eased my misery;then I was full of interest, and began to examine.

I was curious to know what the pink dust was. Suddenly the name of itoccurred to me, though I had never heard of it before. It was FIRE! Iwas as certain of it as a person could be of anything in the world. Sowithout hesitation I named it that--fire.

I had created something that didn't exist before; I had added a newthing to the world's uncountable properties; I realized this, and wasproud of my achievement, and was going to run and find him and tell himabout it, thinking to raise myself in his esteem--but I reflected, anddid not do it. No--he would not care for it. He would ask what it wasgood for, and what could I answer? for if it was not GOOD for something,but only beautiful, merely bea

have also been concerned not to leave out of accountChina's relations with her neighbours. Now that we have a betterknowledge of China's neighbours, the Turks, Mongols, Tibetans, Tunguses,Tai, not confined to the narratives of Chinese, who always speak only of"barbarians", we are better able to realize how closely China has beenassociated with her neighbours from the first day of her history to thepresent time; how greatly she is indebted to them, and how much she hasgiven them. We no longer see China as a great civilization surrounded bybarbarians, but we study the Chinese coming to terms with theirneighbours, who had civilizations of quite different types butnevertheless developed ones.

It is usual to split up Chinese history under the various dynasties thathave ruled China or parts thereof. The beginning or end of a dynastydoes not always indicate the beginning or the end of a definite periodof China's social or cultural development. We have tried to breakChina's history down into the thre

rt and learning, pleasure, sense,

To glean eidolons.

Put in thy chants said he,

No more the puzzling hour nor day, nor segments, parts, put in,Put first before the rest as light for all and entrance-song of all,

That of eidolons.

Ever the dim beginning,

Ever the growth, the rounding of the circle,

Ever the summit and the merge at last, (to surely start again,)

Eidolons! eidolons!

Ever the mutable,

Ever materials, changing, crumbling, re-cohering,

Ever the ateliers, the factories divine,

Issuing eidolons.

Lo, I or you,

Or woman, man, or state, known or unknown,

We seeming solid wealth, strength, beauty build,

But really build eidolons.

The ostent evanescent,

The substance of an artist's mood or savan's studies long,

Or warrior's, martyr's, hero's toils,

To fashion his eidolon.

Of every human life,

(The units gather'd, posted, not a thought, emotion, deed, le

eateningly, and offhe went again. "Mumps one pound, that is what I have put down,but I daresay it will be more like thirty shillings -- don'tspeak -- measles one five, German measles half a guinea, makestwo fifteen six -- don't waggle your finger -- whooping-cough,say fifteen shillings" -- and so on it went, and it added updifferently each time; but at last Wendy just got through,with mumps reduced to twelve six, and the two kinds of measlestreated as one.

There was the same excitement over John, and Michael had even anarrower squeak; but both were kept, and soon, you might have seenthe three of them going in a row to Miss Fulsom's Kindergartenschool, accompanied by their nurse.

Mrs. Darling loved to have everything just so, and Mr. Darlinghad a passion for being exactly like his neighbours; so, ofcourse, they had a nurse. As they were poor, owing to the amountof milk the children drank, this nurse was a prim Newfoundlanddog, called Nana, who had belonged to no one in particular un

s that there is some mischief afoot."

"If you said 'hope' instead of 'fear,' it would be nearer the truth, I'm thinking, Mr. Holmes," the inspector answered, with a knowing grin. "Well, maybe a wee nip would keep out the raw morning chill. No, I won't smoke, I thank you. I'll have to be pushing on my way; for the early hours of a case are the precious ones, as no man knows better than your own self. But--but--"

The inspector had stopped suddenly, and was staring with a look of absolute amazement at a paper upon the table. It was the sheet upon which I had scrawled the enigmatic message.

"Douglas!" he stammered. "Birlstone! What's this, Mr. Holmes? Man, it's witchcraft! Where in the name of all that is wonderful did you get those names?"

"It is a cipher that Dr. Watson and I have had occasion to solve. But why--what's amiss with the names?"

The inspector looked from one to the other of us in dazed astonishment. "Just this," said he, "that Mr. Douglas of Birlstone Manor House

That night, when supper was finished and they sat on the oblong box and pulled at their pipes, the circle of gleaming eyes drew in even closer than before.

"I wisht they'd spring up a bunch of moose or something, an' go away an' leave us alone," Bill said.

Henry grunted with an intonation that was not all sympathy, and for a quarter of an hour they sat on in silence, Henry staring at the fire, and Bill at the circle of eyes that burned in the darkness just beyond the firelight.

"I wisht we was pullin' into McGurry right now," he began again.

"Shut up your wishin' and your croakin'," Henry burst out angrily. "Your stomach's sour. That's what's ailin' you. Swallow a spoonful of sody, an' you'll sweeten up wonderful an' be more pleasant company."

In the morning Henry was aroused by fervid blasphemy that proceeded from the mouth of Bill. Henry propped himself up on an elbow and looked to see his comrade standing among the dogs beside the replenished fire, his a

y give them occasionally will be of far greater assistance than a yearly allowance, because they would only enlarge their style of living if they felt sure of a larger income, and would not be sixpence the richer for it at the end of the year. It will certainly be much the best way. A present of fifty pounds, now and then, will prevent their ever being distressed for money, and will, I think, be amply discharging my promise to my father."

"To be sure it will. Indeed, to say the truth, I am convinced within myself that your father had no idea of your giving them any money at all. The assistance he thought of, I dare say, was only such as might be reasonably expected of you; for instance, such as looking out for a comfortable small house for them, helping them to move their things, and sending them presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season. I'll lay my life that he meant nothing farther; indeed, it would be very strange and unreasonable if he did. Do but consider, my dear Mr. D

're good, you're good.

Chapter Two

I came out of the bathroom with 30 seconds left on the ticker, and started walking briskly towards the conference room. Miranda was trotting immediately behind.

"What's the meeting about?" I asked, nodding to Drew Roberts as I passed his office.

"He didn't say," Miranda said.

"Do we know who else is in the meeting?"

"He didn't say," Miranda said.

The second-floor conference room sits adjacent to Carl's office, which is at the smaller end of our agency's vaguely egg-shaped building. The building itself has been written up in Architectural Digest, which described it as a "Four-way collision between Frank Gehry, Le Corbousier, Jay Ward and the salmonella bacteria." It's unfair to the salmonella bacteria. My office is stacked on the larger arc of the egg on the first floor, along with the offices of all the other junior agents. After today, a second-floor, little-arc office was

ting that all philosophers, in so far as they have beendogmatists, have failed to understand women--that the terribleseriousness and clumsy importunity with which they have usuallypaid their addresses to Truth, have been unskilled and unseemlymethods for winning a woman? Certainly she has never allowedherself to be won; and at present every kind of dogma stands withsad and discouraged mien--IF, indeed, it stands at all! For thereare scoffers who maintain that it has fallen, that all dogma lieson the ground--nay more, that it is at its last gasp. But tospeak seriously, there are good grounds for hoping that alldogmatizing in philosophy, whatever solemn, whatever conclusiveand decided airs it has assumed, may have been only a noblepuerilism and tyronism; and probably the time is at hand when itwill be once and again understood WHAT has actually sufficed forthe basis of such imposing and absolute philosophical edifices asthe dogmatists have hitherto reared: perhaps some popularsuperstition of imm

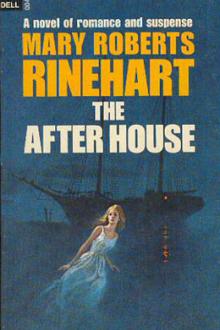

the summer with unimpaired cheerfulness, confiding to me that he secured his luncheons free at the soda counter. He came frequently to see me, bringing always a pocketful of chewing gum, which he assured me was excellent to allay the gnawings of hunger, and later, as my condition warranted it, small bags of gum-drops and other pharmacy confections.

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

ch of delicate pink dust in the hole. Iput my finger in, to feel it, and said OUCH! and took it out again. Itwas a cruel pain. I put my finger in my mouth; and by standing first onone foot and then the other, and grunting, I presently eased my misery;then I was full of interest, and began to examine.

I was curious to know what the pink dust was. Suddenly the name of itoccurred to me, though I had never heard of it before. It was FIRE! Iwas as certain of it as a person could be of anything in the world. Sowithout hesitation I named it that--fire.

I had created something that didn't exist before; I had added a newthing to the world's uncountable properties; I realized this, and wasproud of my achievement, and was going to run and find him and tell himabout it, thinking to raise myself in his esteem--but I reflected, anddid not do it. No--he would not care for it. He would ask what it wasgood for, and what could I answer? for if it was not GOOD for something,but only beautiful, merely bea