is one of the most common of errors, and one of the most difficult to avoid, while their right use gives to style cohesion, firmness, and compactness, and is an important aid to perspicuity. To the text of the synonyms is appended a set of Questions and Examples to adapt the work for use as a text-book. Aside from the purposes of the class-room, this portion will be found of value to the individual student. Excepting those who have made a thorough study of language most persons will discover with surprise how difficult it is to answer any set of the Questions or to fill the blanks in the Examples without referring to the synonym treatment in Part I., or to a dictionary, and how rarely they can give any intelligent reason for preference even among familiar words. There are few who can study such a work without finding occasion to correct some errors into which they have unconsciously fallen, and without coming to a new delight in the use of language from a fuller knowledge of its resources and a clearer sense

angry. But his strength ebbed, his eyesglazed, and he knew nothing when the train was flagged and the twomen threw him into the baggage car.

The next he knew, he was dimly aware that his tongue was hurtingand that he was being jolted along in some kind of a conveyance.The hoarse shriek of a locomotive whistling a crossing told himwhere he was. He had travelled too often with the Judge not toknow the sensation of riding in a baggage car. He opened hiseyes, and into them came the unbridled anger of a kidnapped king.The man sprang for his throat, but Buck was too quick for him.His jaws closed on the hand, nor did they relax till his senseswere choked out of him once more.

"Yep, has fits," the man said, hiding his mangled hand from thebaggageman, who had been attracted by the sounds of struggle."I'm takin' 'm up for the boss to 'Frisco. A crack dog-doctorthere thinks that he can cure 'm."

Concerning that night's ride, the man spoke most eloquently forhimself, in a l

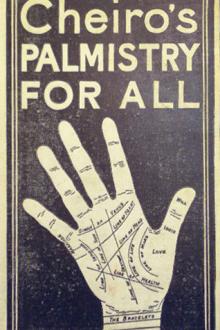

them to the readers of the American Edition of Palmistry for All.

CHEIRO.

LONDON.

INTRODUCTION

It was on July 21, 1894, that I had the honour of meeting Lord Kitchener and getting the autographed impression of his right hand, which I now publish for the first time as frontispiece to this volume. The day I had this interview, Lord Kitchener, or, as he was then, Major-General Kitchener, was at the War Office, and to take this impression had to use the paper on his table, and, strangely enough, the imprint of the War Office may be seen at the top of the second finger--in itself perhaps a premonition that he would one day be the controlling force of that great department.

Lord Kitchener was at that moment Sirdar of the Egyptian Army. He had returned to England to tender his resignation on account of some hostile criticism about "the Abbas affair," and so I took the opportunity of his being in England to ask him to allow me to add his hand to my collection, which ev

m grasp my hair and my shoulder: he had closed with a desperate thing. I really saw in him a tyrant, a murderer. I felt a drop or two of blood from my head trickle down my neck, and was sensible of somewhat pungent suffering: these sensations for the time predominated over fear, and I received him in frantic sort. I don't very well know what I did with my hands, but he called me "Rat! Rat!" and bellowed out aloud. Aid was near him: Eliza and Georgiana had run for Mrs. Reed, who was gone upstairs: she now came upon the scene, followed by Bessie and her maid Abbot. We were parted: I heard the words -

"Dear! dear! What a fury to fly at Master John!"

"Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!"

Then Mrs. Reed subjoined -

"Take her away to the red-room, and lock her in there." Four hands were immediately laid upon me, and I was borne upstairs.

CHAPTER II

I resisted all the way: a new thing for me, and

ohn left me, and a few minutes later I saw him from my window walking slowly across the grass arm in arm with Cynthia Murdoch. I heard Mrs. Inglethorp call "Cynthia" impatiently, and the girl started and ran back to the house. At the same moment, a man stepped out from the shadow of a tree and walked slowly in the same direction. He looked about forty, very dark with a melancholy clean-shaven face. Some violent emotion seemed to be mastering him. He looked up at my window as he passed, and I recognized him, though he had changed much in the fifteen years that had elapsed since we last met. It was John's younger brother, Lawrence Cavendish. I wondered what it was that had brought that singular expression to his face.

Then I dismissed him from my mind, and returned to the contemplation of my own affairs.

The evening passed pleasantly enough; and I dreamed that night of that enigmatical woman, Mary Cavendish.

The next morning dawned bright and sunny, and I was full of the anticipation of a d

in politestudies.'CHAP. VII. Tsze-hsia said, 'If a man withdraws his mind fromthe love of beauty, and applies it as sincerely to the love of thevirtuous; if, in serving his parents, he can exert his utmost strength;

if, in serving his prince, he can devote his life; if, in his intercoursewith his friends, his words are sincere:-- although men say that hehas not learned, I will certainly say that he has.'CHAP. VIII. 1. The Master said, 'If the scholar be not grave, hewill not call forth any veneration, and his learning will not be solid.2. 'Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles.3. 'Have no friends not equal to yourself.4. 'When you have faults, do not fear to abandon them.'CHAP. IX. The philosopher Tsang said, 'Let there be a carefulattention to perform the funeral rites to parents, and let them befollowed when long gone with the ceremonies of sacrifice;-- thenthe virtue of the people will resume its proper excellence.'

CHAP. X. 1. Tsze-ch'in asked Tsze-kung,

ly analyzing the mysteries of the human mind; such tales of illusion and banter as "The Premature Burial" and "The System of Dr. Tarr and Professor Fether"; such bits of extravaganza as "The Devil in the Belfry" and "The Angel of the Odd"; such tales of adventure as "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym"; such papers of keen criticism and review as won for Poe the enthusiastic admiration of Charles Dickens, although they made him many enemies among the over-puffed minor American writers so mercilessly exposed by him; such poems of beauty and melody as "The Bells," "The Haunted Palace," "Tamerlane," "The City in the Sea" and "The Raven." What delight for the jaded senses of the reader is this enchanted domain of wonder-pieces! What an atmosphere of beauty, music, color! What resources of imagination, construction, analysis and absolute art! One might almost sympathize with Sarah Helen Whitman, who, confessing to a half faith in the old superstition of the significance of anagrams, found, in the transposed letter

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he camecloser to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back asfar as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfullydown into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're tobe let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to giveme a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles."He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again."Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him withboth hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keepupright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I couldattend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll,

"I'd like to," said Stella. "It would be a lot of fun."

"Come out Saturday evening and stay all night. He's home then."

"I will," said Stella. "Won't that be fine!"

"I believe you like him!" laughed Myrtle.

"I think he's awfully nice," said Stella, simply.

The second meeting happened on Saturday evening as arranged, when he came home from his odd day at his father's insurance office. Stella had come to supper. Eugene saw her through the open sitting room door, as he bounded upstairs to change his clothes, for he had a fire of youth which no sickness of stomach or weakness of lungs could overcome at this age. A thrill of anticipation ran over his body. He took especial pains with his toilet, adjusting a red tie to a nicety, and parting his hair carefully in the middle. He came down after a while, conscious that he had to say something smart, worthy of himself, or she would not see how attractive he was; and yet he was fearful as to the result. When he entered the sittin

to a dim sort of light not far from the docks, and heard a forlorn creaking in the air; and looking up, saw a swinging sign over the door with a white painting upon it, faintly representing a tall straight jet of misty spray, and these words underneath--"The Spouter Inn:--Peter Coffin."

Coffin?--Spouter?--Rather ominous in that particular connexion, thought I. But it is a common name in Nantucket, they say, and I suppose this Peter here is an emigrant from there. As the light looked so dim, and the place, for the time, looked quiet enough, and the dilapidated little wooden house itself looked as if it might have been carted here from the ruins of some burnt district, and as the swinging sign had a poverty-stricken sort of creak to it, I thought that here was the very spot for cheap lodgings, and the best of pea coffee.

It was a queer sort of place--a gable-ended old house, one side palsied as it were, and leaning over sadly. It stood on a sharp bleak corner, where that tempestuous wind Euroclydo

is one of the most common of errors, and one of the most difficult to avoid, while their right use gives to style cohesion, firmness, and compactness, and is an important aid to perspicuity. To the text of the synonyms is appended a set of Questions and Examples to adapt the work for use as a text-book. Aside from the purposes of the class-room, this portion will be found of value to the individual student. Excepting those who have made a thorough study of language most persons will discover with surprise how difficult it is to answer any set of the Questions or to fill the blanks in the Examples without referring to the synonym treatment in Part I., or to a dictionary, and how rarely they can give any intelligent reason for preference even among familiar words. There are few who can study such a work without finding occasion to correct some errors into which they have unconsciously fallen, and without coming to a new delight in the use of language from a fuller knowledge of its resources and a clearer sense

angry. But his strength ebbed, his eyesglazed, and he knew nothing when the train was flagged and the twomen threw him into the baggage car.

The next he knew, he was dimly aware that his tongue was hurtingand that he was being jolted along in some kind of a conveyance.The hoarse shriek of a locomotive whistling a crossing told himwhere he was. He had travelled too often with the Judge not toknow the sensation of riding in a baggage car. He opened hiseyes, and into them came the unbridled anger of a kidnapped king.The man sprang for his throat, but Buck was too quick for him.His jaws closed on the hand, nor did they relax till his senseswere choked out of him once more.

"Yep, has fits," the man said, hiding his mangled hand from thebaggageman, who had been attracted by the sounds of struggle."I'm takin' 'm up for the boss to 'Frisco. A crack dog-doctorthere thinks that he can cure 'm."

Concerning that night's ride, the man spoke most eloquently forhimself, in a l

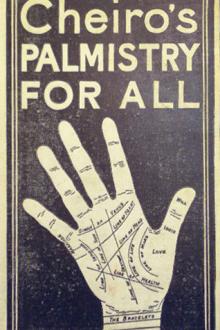

them to the readers of the American Edition of Palmistry for All.

CHEIRO.

LONDON.

INTRODUCTION

It was on July 21, 1894, that I had the honour of meeting Lord Kitchener and getting the autographed impression of his right hand, which I now publish for the first time as frontispiece to this volume. The day I had this interview, Lord Kitchener, or, as he was then, Major-General Kitchener, was at the War Office, and to take this impression had to use the paper on his table, and, strangely enough, the imprint of the War Office may be seen at the top of the second finger--in itself perhaps a premonition that he would one day be the controlling force of that great department.

Lord Kitchener was at that moment Sirdar of the Egyptian Army. He had returned to England to tender his resignation on account of some hostile criticism about "the Abbas affair," and so I took the opportunity of his being in England to ask him to allow me to add his hand to my collection, which ev

m grasp my hair and my shoulder: he had closed with a desperate thing. I really saw in him a tyrant, a murderer. I felt a drop or two of blood from my head trickle down my neck, and was sensible of somewhat pungent suffering: these sensations for the time predominated over fear, and I received him in frantic sort. I don't very well know what I did with my hands, but he called me "Rat! Rat!" and bellowed out aloud. Aid was near him: Eliza and Georgiana had run for Mrs. Reed, who was gone upstairs: she now came upon the scene, followed by Bessie and her maid Abbot. We were parted: I heard the words -

"Dear! dear! What a fury to fly at Master John!"

"Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!"

Then Mrs. Reed subjoined -

"Take her away to the red-room, and lock her in there." Four hands were immediately laid upon me, and I was borne upstairs.

CHAPTER II

I resisted all the way: a new thing for me, and

ohn left me, and a few minutes later I saw him from my window walking slowly across the grass arm in arm with Cynthia Murdoch. I heard Mrs. Inglethorp call "Cynthia" impatiently, and the girl started and ran back to the house. At the same moment, a man stepped out from the shadow of a tree and walked slowly in the same direction. He looked about forty, very dark with a melancholy clean-shaven face. Some violent emotion seemed to be mastering him. He looked up at my window as he passed, and I recognized him, though he had changed much in the fifteen years that had elapsed since we last met. It was John's younger brother, Lawrence Cavendish. I wondered what it was that had brought that singular expression to his face.

Then I dismissed him from my mind, and returned to the contemplation of my own affairs.

The evening passed pleasantly enough; and I dreamed that night of that enigmatical woman, Mary Cavendish.

The next morning dawned bright and sunny, and I was full of the anticipation of a d

in politestudies.'CHAP. VII. Tsze-hsia said, 'If a man withdraws his mind fromthe love of beauty, and applies it as sincerely to the love of thevirtuous; if, in serving his parents, he can exert his utmost strength;

if, in serving his prince, he can devote his life; if, in his intercoursewith his friends, his words are sincere:-- although men say that hehas not learned, I will certainly say that he has.'CHAP. VIII. 1. The Master said, 'If the scholar be not grave, hewill not call forth any veneration, and his learning will not be solid.2. 'Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles.3. 'Have no friends not equal to yourself.4. 'When you have faults, do not fear to abandon them.'CHAP. IX. The philosopher Tsang said, 'Let there be a carefulattention to perform the funeral rites to parents, and let them befollowed when long gone with the ceremonies of sacrifice;-- thenthe virtue of the people will resume its proper excellence.'

CHAP. X. 1. Tsze-ch'in asked Tsze-kung,

ly analyzing the mysteries of the human mind; such tales of illusion and banter as "The Premature Burial" and "The System of Dr. Tarr and Professor Fether"; such bits of extravaganza as "The Devil in the Belfry" and "The Angel of the Odd"; such tales of adventure as "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym"; such papers of keen criticism and review as won for Poe the enthusiastic admiration of Charles Dickens, although they made him many enemies among the over-puffed minor American writers so mercilessly exposed by him; such poems of beauty and melody as "The Bells," "The Haunted Palace," "Tamerlane," "The City in the Sea" and "The Raven." What delight for the jaded senses of the reader is this enchanted domain of wonder-pieces! What an atmosphere of beauty, music, color! What resources of imagination, construction, analysis and absolute art! One might almost sympathize with Sarah Helen Whitman, who, confessing to a half faith in the old superstition of the significance of anagrams, found, in the transposed letter

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he camecloser to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back asfar as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfullydown into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're tobe let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to giveme a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles."He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again."Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him withboth hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keepupright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I couldattend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll,

"I'd like to," said Stella. "It would be a lot of fun."

"Come out Saturday evening and stay all night. He's home then."

"I will," said Stella. "Won't that be fine!"

"I believe you like him!" laughed Myrtle.

"I think he's awfully nice," said Stella, simply.

The second meeting happened on Saturday evening as arranged, when he came home from his odd day at his father's insurance office. Stella had come to supper. Eugene saw her through the open sitting room door, as he bounded upstairs to change his clothes, for he had a fire of youth which no sickness of stomach or weakness of lungs could overcome at this age. A thrill of anticipation ran over his body. He took especial pains with his toilet, adjusting a red tie to a nicety, and parting his hair carefully in the middle. He came down after a while, conscious that he had to say something smart, worthy of himself, or she would not see how attractive he was; and yet he was fearful as to the result. When he entered the sittin

to a dim sort of light not far from the docks, and heard a forlorn creaking in the air; and looking up, saw a swinging sign over the door with a white painting upon it, faintly representing a tall straight jet of misty spray, and these words underneath--"The Spouter Inn:--Peter Coffin."

Coffin?--Spouter?--Rather ominous in that particular connexion, thought I. But it is a common name in Nantucket, they say, and I suppose this Peter here is an emigrant from there. As the light looked so dim, and the place, for the time, looked quiet enough, and the dilapidated little wooden house itself looked as if it might have been carted here from the ruins of some burnt district, and as the swinging sign had a poverty-stricken sort of creak to it, I thought that here was the very spot for cheap lodgings, and the best of pea coffee.

It was a queer sort of place--a gable-ended old house, one side palsied as it were, and leaning over sadly. It stood on a sharp bleak corner, where that tempestuous wind Euroclydo