Biology by Karl Irvin Baguio (smallest ebook reader txt) 📖

- Author: Karl Irvin Baguio

Book online «Biology by Karl Irvin Baguio (smallest ebook reader txt) 📖». Author Karl Irvin Baguio

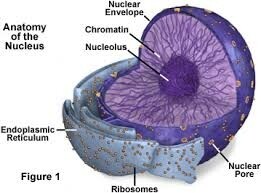

In eukaryotic cells (see Chapter 3), the structure and contents of the nucleus are of fundamental importance to an understanding of cell reproduction. The nucleus contains the hereditary material (DNA) of the cell assembled into chromosomes. In addition, the nucleus usually contains one or more prominent nucleoli (dense bodies that are the site of ribosome synthesis).

The nucleus is surrounded by a nuclear envelope consisting of a double membrane that is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. Transport of molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm is accomplished through a series of nuclear pores lined with proteins that facilitate the passage of molecules out of the nucleus. The proteins provide a certain measure of selectivity in the passage of molecules across the nuclear membrane.

The nuclear material consists of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) organized into long strands. The strands of DNA are composed of nucleotides bonded to one another by covalent bonds. DNA molecules are extremely long relative to the cell; there are approximately 6 feet of DNA in a single human cell. However, in the chromosome, the DNA is condensed and packaged with protein into manageable bodies. The mass of DNA material and its associated protein is chromatin.

To form chromatin, the DNA molecule is wound around globules of a protein called histone. The units formed in this way are nucleosomes. Millions of nucleosomes are connected by short stretches of histone protein, much like beads on a string. The configuration of the nucleosomes in a coil causes additional coiling of the DNA and the eventual formation of the chromosome.

Figure 7.1: Anatomy of the Nucleus

Chapter 8: Meiosis and Gamete Formation

Meiosis

Most plant and animal cells are diploid. The term diploid is derived from the Greek diplos, meaning “double” or “two”; the term implies that the cells of plants and animals have pairs of chromosomes. In human cells, for example, 46 chromosomes are organized in 23 pairs. Hence, human cells are diploid in that they have a pair of 23 individual chromosomes.

During sexual reproduction, the sex cells of parent organisms unite with one another and form a fertilized egg cell (zygote). In this situation, each sex cell is a gamete. The gametes of human cells are haploid, from the Greek haplos, meaning “single.” This term implies that each gamete contains half of the 46 chromosomes—23 chromosomes in humans. When the human gametes unite with one another, the original diploid condition of 46 chromosomes is reestablished. Mitosis then brings about the development of the diploid cell into a multicellular organism.

The process by which the chromosome number is halved during gamete formation is meiosis. In meiosis, a cell containing the diploid number of chromosomes is converted into four cells, each having the haploid number of chromosomes. In human cells undergoing meiosis, for instance, a cell containing 46 chromosomes yields four cells, each with 23 chromosomes.

Meiosis occurs by a series of steps that resemble the steps of mitosis. Two major phases of meiosis occur: meiosis I and meiosis II. During meiosis I, a single cell divides into two. During meiosis II, those two cells each divide again. The same demarcating phases of mitosis take place in meiosis I and meiosis II—prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—but with some variations contained therein.

As shown in Figure 8-1, first, the chromosomes of a cell are divided into two cells. The chromosomes of the two cells then separate and pass into four daughter cells. The parent cell is diploid, while each of the daughter cells has a single set of chromosomes and is haploid. Synapsis and crossing over occur in the prophase I stage.

Figure 8-1 The process of meiosis, in which four haploid cells are formed.

The members of each chromosome pair within a cell are called homologous chromosomes. Homologous chromosomes are similar but not identical. They may carry different versions of the same genetic information. For instance, one homologous chromosome may carry the information for blond hair while the other homologous chromosome may carry the information for black hair.

Meiosis

As a cell prepares to enter meiosis, each of its chromosomes has duplicated in the synthesis stage (S) of the cell cycle, as in mitosis. Each chromosome thus consists of two sister chromatids.

Meiosis I

At the beginning of meiosis I, a human cell contains 46 chromosomes, or 92 chromatids (the same number as during mitosis). Meiosis I proceeds through the following phases:

Prophase I: Prophase I is similar in some ways to prophase in mitosis. The chromatids shorten and thicken and become visible under a microscope. An important difference, however, is that a process called synapsis occurs. Synapsis is when the homologous chromosomes migrate toward one another and join to form a tetrad (the combination of four chromatids, two from each homologous chromosome). A second process called crossing over also takes place during prophase I. In this process, segments of DNA from one chromatid in the tetrad pass to another chromatid in the tetrad. These exchanges of chromosomal segments occur in a complex and poorly understood manner. They result in a genetically new chromatid. Crossing over is an important driving force of evolution. After crossing over has taken place, the homologous pair of chromosomes is genetically different.

Metaphase I: In metaphase I of meiosis, the tetrads align on the equatorial plate (as in mitosis). The centromeres attach to spindle fibers, which extend from the poles of the cell. One centromere attaches per spindle fiber.

Anaphase I: In anaphase I, the homologous chromosomes or tetrads separate. One homologous chromosome (consisting of two chromatids) moves to one side of the cell, while the other homologous chromosome (consisting of two chromatids) moves to the other side of the cell. The result is that 23 chromosomes (each consisting of two chromatids) move to one pole, and 23 chromosomes (each consisting of two chromatids) move to the other pole. Essentially, the chromosome number of the cell is halved once meiosis I is completed. For this reason the process is a reduction-division.

Telophase I: In telophase I of meiosis, the nucleus reorganizes, the chromosomes become chromatin, and the cell membrane begins to pinch inward. Cytokinesis occurs immediately following telophase I. This process occurs differently in plant and animal cells, just as in mitosis.

Meiosis II

Meiosis II is the second major subdivision of meiosis. It occurs in essentially the same way as mitosis. In meiosis II, a cell contains a single set of chromosomes. Each chromosome, however, still has its duplicated sister chromatid attached. Meiosis II segregates the sister chromatids into separate cells. Meiosis II proceeds through the following phases:

Prophase II: Prophase II is similar to the prophase of mitosis. The chromatin material condenses, and each chromosome contains two chromatids attached by the centromere. The 23 chromatid pairs, a total of 46 chromatids, then move to the equatorial plate.

Metaphase II: In metaphase II of meiosis, the 23 chromatid pairs gather at the center of the cell prior to separation. This process is identical to metaphase in mitosis, except that this is occurring in a haploid versus a diploid cell.

Anaphase II: During anaphase II of meiosis, the centromeres divide and sister chromatids separate, at which time they are referred to as non-replicated chromosomes. Spindle fibers move chromosomes to each pole. In all, 23 chromosomes move to each pole. The forces and attachments that operate in mitosis also operate in anaphase II.

Telophase II: During telophase II, the chromosomes gather at the poles of the cells and become indistinct. Again, they form a mass of chromatin. The nuclear envelope develops, the nucleoli reappear, and the cells undergo cytokinesis.

During meiosis II, each cell containing 46 chromatids yields two cells, each with 23 chromosomes. Originally, there were two cells that underwent meiosis II; therefore, the result of meiosis II is four cells, each with 23 chromosomes. Each of the four cells is haploid; that is, each cell contains a single set of chromosomes.

The 23 chromosomes in the four cells from meiosis are not identical because crossing over has taken place in prophase I. The crossing over yields genetic variation so that each of the four resulting cells from meiosis differs from the other three. Thus, meiosis provides a mechanism for producing variations in the chromosomes. Also, it accounts for the formation of four haploid cells from a single diploid cell.

Meiosis in Humans

In humans, meiosis is the process by which sperm cells and egg cells are produced. In the male, meiosis takes place after puberty. Diploid cells within the testes undergo meiosis to produce haploid sperm cells with 23 chromosomes. A single diploid cell yields four haploid sperm cells through meiosis.

In females, meiosis begins during the fetal stage when a series of diploid cells enter meiosis I. At the conclusion of meiosis I, the process comes to a halt, and the cells gather in the ovaries. At puberty, meiosis resumes. One cell at the end of meiosis I enters meiosis II each month. The result of meiosis II is a single egg cell per cycle (the other meiotic cells disintegrate). Each egg cell contains 23 chromosomes and is haploid.

The union of the egg cell and the sperm cell leads to the formation of a fertilized egg cell with 46 chromosomes, or 23 pairs. Fertilization restores the diploid number of chromosomes. The fertilized egg cell, a diploid, is a zygote. Further divisions of the zygote by mitosis eventually yield a complete human being.

Chapter 9: Classical (Mendelian) GeneticsIntroduction to Genetics

Genetics is the study of how genes bring about characteristics, or traits, in living things and how those characteristics are inherited. Genes are specific sequences of nucleotides that code for particular proteins. Through the processes of meiosis and sexual reproduction, genes are transmitted from one generation to the next.

Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel developed the science of genetics. Mendel performed his experiments in the 1860s and 1870s, but the scientific community did not accept his work until early in the twentieth century. Because the principles established by Mendel form the basis for genetics, the science is often referred to as Mendelian genetics. It is also called classical genetics to distinguish it from another branch of biology known as molecular genetics (see Chapter 10).

Mendel believed that factors pass from parents to their offspring, but he did not know of the existence of DNA. Modern scientists accept that genes are composed

The desire to acquire knowledge about the surrounding world and human society is quite natural and understandable for a person. Life is so developed that an uneducated person will never occupy a high position in any field. Humanity in its mass, and each person individually, develops objectively, regardless of certain life circumstances and obstacles, but with different intensity. The speed of development depends on the quality of training.

The desire to acquire knowledge about the surrounding world and human society is quite natural and understandable for a person. Life is so developed that an uneducated person will never occupy a high position in any field. Humanity in its mass, and each person individually, develops objectively, regardless of certain life circumstances and obstacles, but with different intensity. The speed of development depends on the quality of training.

Comments (0)