Genre Fantasy. Page - 23

nly look up and say 'who am I then? answer me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I'll come up: if not, I'll stay down here till I'm somebody else--but, oh dear!" cried Alice with a sudden burst of tears, "I do wish they would put their heads down! I am so tired of being all alone here!"

As she said this, she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to find she had put on one of the rabbit's little gloves while she was talking. "How can I have done that?" thought she, "I must be growing small again." She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: soon she found out that the reason of it was the nosegay she held in her hand: she dropped it hastily, just in time to save herself from shrinking away altogether, and found that she was now only three inches high.

"Now for the garden!" cried Alice, as she hurried back to the little door, but the little door wa

have been "hallucinated," and proceeds to give the theory of sensory hallucination. She forgets that, by her own showing, there is no reason to suppose that anybody has been hallucinated at all. Someone (unknown) has met a nurse (unnamed) who has talked to a soldier (anonymous) who has seen angels. But that is not evidence; and not even Sam Weller at his gayest would have dared to offer it as such in the Court of Common Pleas. So far, then, nothing remotely approaching proof has been offered as to any supernatural intervention during the Retreat from Mons. Proof may come; if so, it will be interesting and more than interesting.

But, taking the affair as it stands at present, how is it that a nation plunged in materialism of the grossest kind has accepted idle rumours and gossip of the supernatural as certain truth? The answer is contained in the question: it is precisely because our whole atmosphere is materialist that we are ready to credit anything--save the truth. Separate a man from

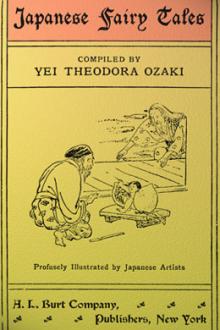

r description as they seemed toneed or as pleased me, and in one or two instances I have gatheredin an incident from another version. At all times, among my friends,both young and old, English or American, I have always found eagerlisteners to the beautiful legends and fairy tales of Japan, and intelling them I have also found that they were still unknown to thevast majority, and this has encouraged me to write them for thechildren of the West.

Y. T. O.

Tokio, 1908.

CONTENTS.

MY LORD BAG OF RICE

THE TONGUE-CUT SPARROW

THE STORY OF URASHIMA TARO, THE FISHER LAD

THE FARMER AND THE BADGER

THE "shinansha," OR THE SOUTH POINTING CARRIAGE

THE ADVENTURES OF KINTARO, THE GOLDEN BOY

THE STORY OF PRINCESS HASE

THE STORY OF THE MAN WHO DID NOT WISH TO DIE

THE BAMBOO-CUTTER AND THE MOON-CHILD

THE MIRROR OF MATSUYAMA

THE GOBLIN OF ADACHIGAHARA

THE SAGACIOUS MONKEY AND THE BOAR

THE HAPPY HUNTER AND THE SKILLFUL FISHER

THE STORY OF THE OLD MAN WHO MADE WITHERED

Bracing himself, Thomas stepped through the ward and onto the first step, and had to steady himself against the wall as the effect faded. He shook his head and started up the stairs.

The banister was carved with roses which swayed under a sorcerous breeze only they could sense. Thomas climbed slowly, looking for the next trap. When he stopped at the first landing, he could see that the top of the stairs opened into a long gallery, lit by dozens of candles in mirror-backed sconces. Red draperies framed mythological paintings and classical landscapes. At the far end was a door, guarded on either side by a man-sized statuary niche. One niche held an angel with flowing locks, wings, and a beatific smile. The other niche was empty.

Thomas climbed almost to the head of the stairs, looking up at the archway that was the entrance to the room. Something suspiciously like plaster dust drifted down from the carved bunting.

A tactical error, Thomas thought. Whatever was hiding

earfully hungry, and made terrible havoc among the mice.

Then the queen of the mice held a council.

"These cats will eat every one of us," she said, "if the captain of the ship does not shut the ferocious animals up. Let us send a deputation to him of the bravest among us."

Several mice offered themselves for this mission and set out to find the young captain.

"Captain," said they, "go away quickly from our island, or we shall perish, every mouse of us."

"Willingly," replied the young captain, "upon one condition. That is that you shall first bring me back a bronze ring which some clever magician has stolen from me. If you do not do this I will land all my cats upon your island, and you shall be exterminated."

The mice withdrew in great dismay. "What is to be done?" said the Queen. "How can we find this bronze ring?" She held a new council, calling in mice from every quarter of the globe, but nobody knew where the bronze ring was. Suddenly three mice arrived from a ve

I believe that I hate him as much as you do, but--Oh, Raoul, blood is thicker than water."

"I should today have liked to sample the consistency of his," growled De Coude grimly. "The two deliberately attempted to besmirch my honor, Olga," and then he told her of all that had happened in the smoking-room. "Had it not been for this utter stranger, they had succeeded, for who would have accepted my unsupported word against the damning evidence of those cards hidden on my person? I had almost begun to doubt myself when this Monsieur Tarzan dragged your precious Nikolas before us, and explained the whole cowardly transaction."

"Monsieur Tarzan?" asked the countess, in evident surprise.

"Yes. Do you know him, Olga?"

"I have seen him. A steward pointed him out to me."

"I did not know that he was a celebrity," said the count.

Olga de Coude changed the subject. She discovered suddenly that she might find it difficult to explain just why the steward had pointed out the handsome

who will investigate and send us word of the situation before we get involved. That way, we appear concerned with our neighbors but not foolhardy. I suggest we hire delvers. They will move across the countryside far faster than any of us. They can assess the situation and make first contact with those needing the greatest help."

"Yes, yes," Consprite said quickly. He turned a pen in his fingers. "This is very true. We would not waste time or effort in the less lucrative areas. Any delver worth his salt would surely give us a great advantage." He looked up with a nod of acceptance. "I heartily approve."

"I oppose the measure," Cofort said sullenly. "I do not trust delvers. They always require large payments and no one can ever really tell if they do what they say they do. No one can follow them, no one can check up on them."

"I realize that delvers are expensive," Consprite admitted candidly, "but that's because no one can do the job they can do. I realize that it is difficult to check on

"Is he really an anarchist, then?" she asked.

"Only in that sense I speak of," replied Syme; "or if you prefer it, in that nonsense."

She drew her broad brows together and said abruptly--

"He wouldn't really use--bombs or that sort of thing?"

Syme broke into a great laugh, that seemed too large for his slight and somewhat dandified figure.

"Good Lord, no!" he said, "that has to be done anonymously."

And at that the corners of her own mouth broke into a smile, and she thought with a simultaneous pleasure of Gregory's absurdity and of his safety.

Syme strolled with her to a seat in the corner of the garden, and continued to pour out his opinions. For he was a sincere man, and in spite of his superficial airs and graces, at root a humble one. And it is always the humble man who talks too much; the proud man watches himself too closely. He defended respectability with violence and exaggeration. He grew passionate in his praise of tidiness and propriety. All