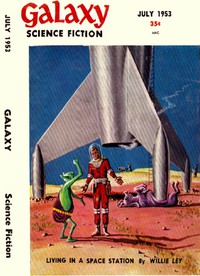

Soldier Boy by Michael Shaara (open ebook TXT) 📖

- Author: Michael Shaara

Book online «Soldier Boy by Michael Shaara (open ebook TXT) 📖». Author Michael Shaara

By MICHAEL SHAARA

Illustrated by EMSH

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction July 1953.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It's one thing to laugh at a man because his job is useless

and outdated—another to depend on him when it suddenly isn't.

In the northland, deep, and in a great cave, by an everburning fire the Warrior sleeps. For this is the resting time, the time of peace, and so shall it be for a thousand years. And yet we shall summon him again, my children, when we are sore in need, and out of the north he will come, and again and again, each time we call, out of the dark and the cold, with the fire in his hands, he will come.

—Scandinavian legend

Throughout the night, thick clouds had been piling in the north; in the morning, it was misty and cold. By eight o'clock a wet, heavy, snow-smelling breeze had begun to set in, and because the crops were all down and the winter planting done, the colonists brewed hot coffee and remained inside. The wind blew steadily, icily from the north. It was well below freezing when, some time after nine, an army ship landed in a field near the settlement.

There was still time. There were some last brief moments in which the colonists could act and feel as they had always done. They therefore grumbled in annoyance. They wanted no soldiers here. The few who had convenient windows stared out with distaste and a mild curiosity, but no one went out to greet them.

After a while a rather tall, frail-looking man came out of the ship and stood upon the hard ground looking toward the village. He remained there, waiting stiffly, his face turned from the wind. It was a silly thing to do. He was obviously not coming in, either out of pride or just plain orneriness.

"Well, I never," a nice lady said.

"What's he just standing there for?" another lady said.

And all of them thought: well, God knows what's in the mind of a soldier, and right away many people concluded that he must be drunk. The seed of peace was deeply planted in these people, in the children and the women, very, very deep. And because they had been taught, oh so carefully, to hate war they had also been taught, quite incidentally, to despise soldiers.

The lone man kept standing in the freezing wind.

Eventually, because even a soldier can look small and cold and pathetic, Bob Rossel had to get up out of a nice, warm bed and go out in that miserable cold to meet him.

The soldier saluted. Like most soldiers, he was not too neat and not too clean and the salute was sloppy. Although he was bigger than Rossel he did not seem bigger. And, because of the cold, there were tears gathering in the ends of his eyes.

"Captain Dylan, sir." His voice was low and did not carry. "I have a message from Fleet Headquarters. Are you in charge here?"

Rossel, a small sober man, grunted. "Nobody's in charge here. If you want a spokesman I guess I'll do. What's up?"

The captain regarded him briefly out of pale blue, expressionless eyes. Then he pulled an envelope from an inside pocket, handed it to Rossel. It was a thick, official-looking thing and Rossel hefted it idly. He was about to ask again what was it all about when the airlock of the hovering ship swung open creakily. A beefy, black-haired young man appeared unsteadily in the doorway, called to Dylan.

"C'n I go now, Jim?"

Dylan turned and nodded.

"Be back for you tonight," the young man called, and then, grinning, he yelled "Catch" and tossed down a bottle. The captain caught it and put it unconcernedly into his pocket while Rossel stared in disgust. A moment later the airlock closed and the ship prepared to lift.

"Was he drunk?" Rossel began angrily. "Was that a bottle of liquor?"

The soldier was looking at him calmly, coldly. He indicated the envelope in Rossel's hand. "You'd better read that and get moving. We haven't much time."

He turned and walked toward the buildings and Rossel had to follow. As Rossel drew near the walls the watchers could see his lips moving but could not hear him. Just then the ship lifted and they turned to watch that, and followed it upward, red spark-tailed, into the gray spongy clouds and the cold.

After a while the ship went out of sight, and nobody ever saw it again.

The first contact Man had ever had with an intelligent alien race occurred out on the perimeter in a small quiet place a long way from home. Late in the year 2360—the exact date remains unknown—an alien force attacked and destroyed the colony at Lupus V. The wreckage and the dead were found by a mailship which flashed off screaming for the army.

When the army came it found this: Of the seventy registered colonists, thirty-one were dead. The rest, including some women and children, were missing. All technical equipment, all radios, guns, machines, even books, were also missing. The buildings had been burned, so were the bodies. Apparently the aliens had a heat ray. What else they had, nobody knew. After a few days of walking around in the ash, one soldier finally stumbled on something.

For security reasons, there was a detonator in one of the main buildings. In case of enemy attack, Security had provided a bomb to be buried in the center of each colony, because it was important to blow a whole village to hell and gone rather than let a hostile alien learn vital facts about human technology and body chemistry. There was a bomb at Lupus V too, and though it had been detonated it had not blown. The detonating wire had been cut.

In the heart of the camp, hidden from view under twelve inches of earth, the wire had been dug up and cut.

The army could not understand it and had no time to try. After five hundred years of peace and anti-war conditioning the army was small, weak and without respect. Therefore, the army did nothing but spread the news, and Man began to fall back.

In a thickening, hastening stream he came back from the hard-won stars, blowing up his homes behind him, stunned and cursing. Most of the colonists got out in time. A few, the farthest and loneliest, died in fire before the army ships could reach them. And the men in those ships, drinkers and gamblers and veterans of nothing, the dregs of a society which had grown beyond them, were for a long while the only defense Earth had.

This was the message Captain Dylan had brought, come out from Earth with a bottle on his hip.

An obscenely cheerful expression upon his gaunt, not too well shaven face, Captain Dylan perched himself upon the edge of a table and listened, one long booted leg swinging idly. One by one the colonists were beginning to understand. War is huge and comes with great suddenness and always without reason, and there is inevitably a wait, between acts, between the news and the motion, the fear and the rage.

Dylan waited. These people were taking it well, much better than those in the cities had taken it. But then, these were pioneers. Dylan grinned. Pioneers. Before you settle a planet you boil it and bake it and purge it of all possible disease. Then you step down gingerly and inflate your plastic houses, which harden and become warm and impregnable; and send your machines out to plant and harvest; and set up automatic factories to transmute dirt into coffee; and, without ever having lifted a finger, you have braved the wilderness, hewed a home out of the living rock and become a pioneer. Dylan grinned again. But at least this was better than the wailing of the cities.

This Dylan thought, although he was himself no fighter, no man at all by any standards. This he thought because he was a soldier and an outcast; to every drunken man the fall of the sober is a happy thing. He stirred restlessly.

By this time the colonists had begun to realize that there wasn't much to say, and a tall, handsome woman was murmuring distractedly: "Lupus, Lupus—doesn't that mean wolves or something?"

Dylan began to wish they would get moving, these pioneers. It was very possible that the aliens would be here soon, and there was no need for discussion. There was only one thing to do and that was to clear the hell out, quickly and without argument. They began to see it.

But, when the fear had died down, the resentment came. A number of women began to cluster around Dylan and complain, working up their anger. Dylan said nothing. Then the man Rossel pushed forward and confronted him, speaking with a vast annoyance.

"See here, soldier, this is our planet. I mean to say, this is our home. We demand some protection from the fleet. By God, we've been paying the freight for you boys all these years and it's high time you earned your keep. We demand...."

It went on and on while Dylan looked at the clock and waited. He hoped that he could end this quickly. A big gloomy man was in front of him now and giving him that name of ancient contempt, "soldier boy." The gloomy man wanted to know where the fleet was.

"There is no fleet. There are a few hundred half-shot old tubs that were obsolete before you were born. There are four or five new jobs for the brass and the government. That's all the fleet there is."

Dylan wanted to go on about that, to remind them that nobody had wanted the army, that the fleet had grown smaller and smaller ... but this was not the time. It was ten-thirty already and the damned aliens might be coming in right now for all he knew, and all they did was talk. He had realized a long time ago that no peace-loving nation in the history of Earth had ever kept itself strong, and although peace was a noble dream, it was ended now and it was time to move.

"We'd better get going," he finally said, and there was quiet. "Lieutenant Bossio has gone on to your sister colony at Planet Three of this system. He'll return to pick me up by nightfall and I'm instructed to have you gone by then."

For a long moment they waited, and then one man abruptly walked off and the rest followed quickly; in a moment they were all gone. One or two stopped long enough to complain about the fleet, and the big gloomy man said he wanted guns, that's all, and there wouldn't nobody get him off his planet. When he left, Dylan breathed with relief and went out to check the bomb, grateful for the action.

Most of it had to be done in the open. He found a metal bar in the radio shack and began chopping at the frozen ground, following the wire. It was the first thing he had done with his hands in weeks, and it felt fine.

Dylan had been called up out of a bar—he and Bossio—and told what had happened, and in three weeks now they had cleared four colonies. This would be the last, and the tension here was beginning to get to him. After thirty years of hanging around and playing like the town drunk, a man could not be expected to rush out and plug the breach, just like that. It would take time.

He rested, sweating, took a pull from the bottle on his hip.

Before they sent him out on this trip they had made him a captain. Well, that was nice. After thirty years he was a captain. For thirty years he had bummed all over the west end of space, had scraped his way along the outer edges of Mankind, had waited and dozed and patrolled and got drunk, waiting always for something to happen. There were a lot of ways to pass the time while you waited for something to happen, and he had done them all.

Once he had even studied military tactics.

He could not help smiling at that, even now. Damn it, he'd been green. But he'd been only nineteen when his father died—of a hernia, of a crazy fool thing like a hernia that killed him just because he'd worked too long

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)