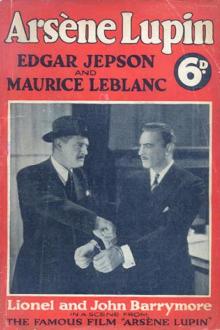

The Eight Strokes of the Clock by Maurice Leblanc (best free ereader .txt) 📖

- Author: Maurice Leblanc

Book online «The Eight Strokes of the Clock by Maurice Leblanc (best free ereader .txt) 📖». Author Maurice Leblanc

The young man folded his arms:

"In any case, monsieur, it seems likely that I should know the truth better than you do."

"Why better? What happened on that tragic night can obviously be known to you only at secondhand. You have no proofs. Neither have Madame d'Imbleval and Madame Vaurois."

"No proofs of what?" exclaimed Jean Louis, losing patience.

"No proofs of the confusion that took place."

"What! Why, it's an absolute certainty! The two children were laid in the same cradle, with no marks to distinguish one from the other; and the nurse was unable to tell...."

"At least, that's her version of it," interrupted R�nine.

"What's that? Her version? But you're accusing the woman."

"I'm accusing her of nothing."

"Yes, you are: you're accusing her of lying. And why should she lie? She had no interest in doing so; and her tears and despair are so much evidence of her good faith. For, after all, the two mothers were there ... they saw the woman weeping ... they questioned her.... And then, I repeat, what interest had she ...?"

Jean Louis was greatly excited. Close beside him, Madame d'Imbleval and Madame Vaurois, who had no doubt been listening behind the doors and who had stealthily entered the room, stood stammering, in amazement:

"No, no ... it's impossible.... We've questioned her over and over again. Why should she tell a lie?..."

"Speak, monsieur, speak," Jean Louis enjoined. "Explain yourself. Give your reasons for trying to cast doubt upon an absolute truth!"

"Because that truth is inadmissible," declared R�nine, raising his voice and growing excited in turn to the point of punctuating his remarks by thumping the table. "No, things don't happen like that. No, fate does not display those refinements of cruelty and chance is not added to chance with such reckless extravagance! It was already an unprecedented chance that, on the very night on which the doctor, his man-servant and his maid were out of the house, the two ladies should be seized with labour-pains at the same hour and should bring two sons into the world at the same time. Don't let us add a still more exceptional event! Enough of the uncanny! Enough of lamps that go out and candles that refuse to burn! No and again no, it is not admissable that a midwife should become confused in the essential details of her trade. However bewildered she may be by the unforeseen nature of the circumstances, a remnant of instinct is still on the alert, so that there is a place prepared for each child and each is kept distinct from the other. The first child is here, the second is there. Even if they are lying side by side, one is on the left and the other on the right. Even if they are wrapped in the same kind of binders, some little detail differs, a trifle which is recorded by the memory and which is inevitably recalled to the mind without any need of reflection. Confusion? I refuse to believe in it. Impossible to tell one from the other? It isn't true. In the world of fiction, yes, one can imagine all sorts of fantastic accidents and heap contradiction on contradiction. But, in the world of reality, at the very heart of reality, there is always a fixed point, a solid nucleus, about which the facts group themselves in accordance with a logical order. I therefore declare most positively that Nurse Boussignol could not have mixed up the two children."

All this he said decisively, as though he had been present during the night in question; and so great was his power of persuasion that from the very first he shook the certainty of those who for more than a quarter of a century had never doubted.

The two women and their son pressed round him and questioned him with breathless anxiety:

"Then you think that she may know ... that she may be able to tell us....?"

He corrected himself:

"I don't say yes and I don't say no. All I say is that there was something in her behaviour during those hours that does not tally with her statements and with reality. All the vast and intolerable mystery that has weighed down upon you three arises not from a momentary lack of attention but from something of which we do not know, but of which she does. That is what I maintain; and that is what happened."

Jean Louis said, in a husky voice:

"She is alive.... She lives at Carhaix.... We can send for her...."

Hortense at once proposed:

"Would you like me to go for her? I will take the motor and bring her back with me. Where does she live?"

"In the middle of the town, at a little draper's shop. The chauffeur will show you. Mlle. Boussignol: everybody knows her...."

"And, whatever you do," added R�nine, "don't warn her in any way. If she's uneasy, so much the better. But don't let her know what we want with her."

Twenty minutes passed in absolute silence. R�nine paced the room, in which the fine old furniture, the handsome tapestries, the well-bound books and pretty knick-knacks denoted a love of art and a seeking after style in Jean Louis. This room was really his. In the adjoining apartments on either side, through the open doors, R�nine was able to note the bad taste of the two mothers.

He went up to Jean Louis and, in a low voice, asked:

"Are they well off?"

"Yes."

"And you?"

"They settled the manor-house upon me, with all the land around it, which makes me quite independent."

"Have they any relations?"

"Sisters, both of them."

"With whom they could go to live?"

"Yes; and they have sometimes thought of doing so. But there can't be any question of that. Once more, I assure you...."

Meantime the car had returned. The two women jumped up hurriedly, ready to speak.

"Leave it to me," said R�nine, "and don't be surprised by anything that I say. It's not a matter of asking her questions but of frightening her, of flurrying her.... The sudden attack," he added between his teeth.

The car drove round the lawn and drew up outside the windows. Hortense sprang out and helped an old woman to alight, dressed in a fluted linen cap, a black velvet bodice and a heavy gathered skirt.

The old woman entered in a great state of alarm. She had a pointed face, like a weasel's, with a prominent mouth full of protruding teeth.

"What's the matter, Madame d'Imbleval?" she asked, timidly stepping into the room from which the doctor had once driven her. "Good day to you, Madame Vaurois."

The ladies did not reply. R�nine came forward and said, sternly:

"Mlle. Boussignol, I have been sent by the Paris police to throw light upon a tragedy which took place here twenty-seven years ago. I have just secured evidence that you have distorted the truth and that, as the result of your false declarations, the birth-certificate of one of the children born in the course of that night is inaccurate. Now false declarations in matters of birth-certificates are misdemeanours punishable by law. I shall therefore be obliged to take you to Paris to be interrogated ... unless you are prepared here and now to confess everything that might repair the consequences of your offence."

The old maid was shaking in every limb. Her teeth were chattering. She was evidently incapable of opposing the least resistance to R�nine.

"Are you ready to confess everything?" he asked.

"Yes," she panted.

"Without delay? I have to catch a train. The business must be settled immediately. If you show the least hesitation, I take you with me. Have you made up your mind to speak?"

"Yes."

He pointed to Jean Louis:

"Whose son is this gentleman? Madame d'Imbleval's?"

"No."

"Madame Vaurois', therefore?"

"No."

A stupefied silence welcomed the two replies.

"Explain yourself," R�nine commanded, looking at his watch.

Then Madame Boussignol fell on her knees and said, in so low and dull a voice that they had to bend over her in order to catch the sense of what she was mumbling:

"Some one came in the evening ... a gentleman with a new-born baby wrapped in blankets, which he wanted the doctor to look after. As the doctor wasn't there, he waited all night and it was he who did it all."

"Did what?" asked R�nine. "What did he do? What happened?"

"Well, what happened was that it was not one child but the two of them that died: Madame d'Imbleval's and Madame Vaurois' too, both in convulsions. Then the gentleman, seeing this, said, 'This shows me where my duty lies. I must seize this opportunity of making sure that my own boy shall be happy and well cared for. Put him in the place of one of the dead children.' He offered me a big sum of money, saying that this one payment would save him the expense of providing for his child every month; and I accepted. Only, I did not know in whose place to put him and whether to say that the boy was Louis d'Imbleval or Jean Vaurois. The gentleman thought a moment and said neither. Then he explained to me what I was to do and what I was to say after he had gone. And, while I was dressing his boy in vest and binders the same as one of the dead children, he wrapped the other in the blankets he had brought with him and went out into the night."

Mlle. Boussignol bent her head and wept. After a moment, R�nine said:

"Your deposition agrees with the result of my investigations."

"Can I go?"

"Yes."

"And is it over, as far as I'm concerned? They won't be talking about this all over the district?"

"No. Oh, just one more question: do you know the man's name?"

"No. He didn't tell me his name."

"Have you ever seen him since?"

"Never."

"Have you anything more to say?"

"No."

"Are you prepared to sign the written text of your confession?"

"Yes."

"Very well. I shall send for you in a week or two. Till then, not a word to anybody."

He saw her to the door and closed it after her. When he returned, Jean Louis was between the two old ladies and all three were holding hands. The bond of hatred and wretchedness which had bound them had suddenly snapped; and this rupture, without requiring them to reflect upon the matter, filled them with a gentle tranquillity of which they were hardly conscious, but which made them serious and thoughtful.

"Let's rush things," said R�nine to Hortense. "This is the decisive moment of the battle. We must get Jean Louis on board."

Hortense seemed preoccupied. She whispered:

"Why did you let the woman go? Were you satisfied with her statement?"

"I don't need to be satisfied. She told us what happened. What more do you want?"

"Nothing.... I don't know...."

"We'll talk about it later, my dear. For the moment, I repeat, we must get Jean Louis on board. And immediately.... Otherwise...."

He turned to the young man:

"You agree with me, don't you, that, things being as they are, it is best for you and Madame Vaurois and Madame d'Imbleval to separate for a time? That will enable you all to see matters more clearly and to decide in perfect freedom what is to be done. Come with us, monsieur. The most pressing thing is to save Genevi�ve Aymard, your fianc�e."

Jean Louis stood perplexed and undecided. R�nine turned to the two women:

"That is your opinion too, I am sure, ladies?"

They nodded.

"You see, monsieur," he said to Jean Louis, "we are all agreed. In great crises, there is nothing like separation ... a few days' respite. Quickly now, monsieur."

And, without giving him time to hesitate, he drove him towards his bedroom to pack up.

Half an hour later, Jean Louis left the manor-house with his new friends.

"And he won't go back until he's married," said R�nine to Hortense, as they were waiting at Carhaix station, to which the car had taken them, while Jean Louis was attending to his luggage. "Everything's for the best. Are you satisfied?"

"Yes, Genevi�ve will be glad," she replied, absently.

When they had taken their seats in the train, R�nine and she repaired to the dining-car. R�nine, who had asked Hortense several questions to which she had replied only in monosyllables, protested:

"What's the matter with you, my child? You look worried!"

"I? Not at all!"

"Yes, yes, I know you. Now, no secrets, no mysteries!"

She smiled:

"Well, since you insist on knowing if I am satisfied, I am bound to admit that of course I am ... as regards my friend Genevi�ve, but that, in another respect--from the point of view of the adventure--I have an uncomfortable sort of feeling...."

"To speak frankly, I haven't 'staggered' you this time?"

"Not very much."

"I seem to you to have played a secondary part. For, after all, what have I done? We arrived. We listened to Jean

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)