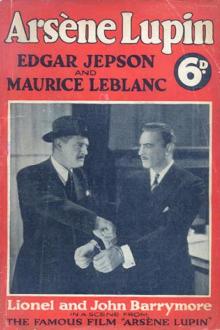

The Eight Strokes of the Clock by Maurice Leblanc (best free ereader .txt) 📖

- Author: Maurice Leblanc

Book online «The Eight Strokes of the Clock by Maurice Leblanc (best free ereader .txt) 📖». Author Maurice Leblanc

"I am to be married in a week, Jean Louis. Come to my rescue, I beseech

you. My friend Hortense and Prince R�nine will help you to overcome the

obstacles that baffle you. Trust them. I love you.

"GENEVI�VE."

He was a rather dull-looking young man, whose very swarthy, lean and bony face certainly bore the expression of melancholy and distress described by Genevi�ve. Indeed, the marks of suffering were visible in all his harassed features, as well as in his sad and anxious eyes.

He repeated Genevi�ve's name over and over again, while looking about him with a distracted air. He seemed to be seeking a course of conduct.

He seemed on the point of offering an explanation but could find nothing to say. The sudden intervention had taken him at a disadvantage, like an unforseen attack which he did not know how to meet.

R�nine felt that the adversary would capitulate at the first summons. The man had been fighting so desperately during the last few months and had suffered so severely in the retirement and obstinate silence in which he had taken refuge that he was not thinking of defending himself. Moreover, how could he do so, now that they had forced their way into the privacy of his odious existence?

"Take my word for it, monsieur," declared R�nine, "that it is in your best interests to confide in us. We are Genevi�ve Aymard's friends. Do not hesitate to speak."

"I can hardly hesitate," he said, "after what you have just heard. This is the life I lead, monsieur. I will tell you the whole secret, so that you may tell it to Genevi�ve. She will then understand why I have not gone back to her ... and why I have not the right to do so."

He pushed a chair forward for Hortense. The two men sat down, and, without any need of further persuasion, rather as though he himself felt a certain relief in unburdening himself, he said:

"You must not be surprised, monsieur, if I tell my story with a certain flippancy, for, as a matter of fact, it is a frankly comical story and cannot fail to make you laugh. Fate often amuses itself by playing these imbecile tricks, these monstrous farces which seem as though they must have been invented by the brain of a madman or a drunkard. Judge for yourself. Twenty-seven years ago, the Manoir d'Elseven, which at that time consisted only of the main building, was occupied by an old doctor who, to increase his modest means, used to receive one or two paying guests. In this way, Madame d'Imbleval spent the summer here one year and Madame Vaurois the following summer. Now these two ladies did not know each other. One of them was married to a Breton of a merchant-vessel and the other to a commercial traveller from the Vend�e.

"It so happened that they lost their husbands at the same time, at a period when each of them was expecting a baby. And, as they both lived in the country, at places some distance from any town, they wrote to the old doctor that they intended to come to his house for their confinement.... He agreed. They arrived almost on the same day, in the autumn. Two small bedrooms were prepared for them, behind the room in which we are sitting. The doctor had engaged a nurse, who slept in this very room. Everything was perfectly satisfactory. The ladies were putting the finishing touches to their baby-clothes and were getting on together splendidly. They were determined that their children should be boys and had chosen the names of Jean and Louis respectively.... One evening the doctor was called out to a case and drove off in his gig with the man-servant, saying that he would not be back till next day. In her master's absence, a little girl who served as maid-of-all-work ran out to keep company with her sweetheart. These accidents destiny turned to account with diabolical malignity. At about midnight, Madame d'Imbleval was seized with the first pains. The nurse, Mlle. Boussignol, had had some training as a midwife and did not lose her head. But, an hour later, Madame Vaurois' turn came; and the tragedy, or I might rather say the tragi-comedy, was enacted amid the screams and moans of the two patients and the bewildered agitation of the nurse running from one to the other, bewailing her fate, opening the window to call out for the doctor or falling on her knees to implore the aid of Providence.... Madame Vaurois was the first to bring a son into the world. Mlle. Boussignol hurriedly carried him in here, washed and tended him and laid him in the cradle prepared for him.... But Madame d'Imbleval was screaming with pain; and the nurse had to attend to her while the newborn child was yelling like a stuck pig and the terrified mother, unable to stir from her bed, fainted.... Add to this all the wretchedness of darkness and disorder, the only lamp, without any oil, for the servant had neglected to fill it, the candles burning out, the moaning of the wind, the screeching of the owls, and you will understand that Mlle. Boussignol was scared out of her wits. However, at five o'clock in the morning, after many tragic incidents, she came in here with the d'Imbleval baby, likewise a boy, washed and tended him, laid him in his cradle and went off to help Madame Vaurois, who had come to herself and was crying out, while Madame d'Imbleval had fainted in her turn. And, when Mlle. Boussignol, having settled the two mothers, but half-crazed with fatigue, her brain in a whirl, returned to the new-born children, she realized with horror that she had wrapped them in similar binders, thrust their feet into similar woolen socks and laid them both, side by side, in the same cradle, so that it was impossible to tell Louis d'Imbleval from Jean Vaurois!... To make matters worse, when she lifted one of them out of the cradle, she found that his hands were cold as ice and that he had ceased to breathe. He was dead. What was his name and what the survivor's?... Three hours later, the doctor found the two women in a condition of frenzied delirium, while the nurse was dragging herself from one bed to the other, entreating the two mothers to forgive her. She held me out first to one, then to the other, to receive their caresses--for I was the surviving child--and they first kissed me and then pushed me away; for, after all, who was I? The son of the widowed Madame d'Imbleval and the late merchant-captain or the son of the widowed Madame Vaurois and the late commercial traveller? There was not a clue by which they could tell.... The doctor begged each of the two mothers to sacrifice her rights, at least from the legal point of view, so that I might be called either Louis d'Imbleval or Jean Vaurois. They refused absolutely. 'Why Jean Vaurois, if he's a d'Imbleval?' protested the one. 'Why Louis d'Imbleval, if he's a Vaurois?' retorted the other. And I was registered under the name of Jean Louis, the son of an unknown father and mother."

Prince R�nine had listened in silence. But Hortense, as the story approached its conclusion, had given way to a hilarity which she could no longer restrain and suddenly, in spite of all her efforts, she burst into a fit of the wildest laughter:

"Forgive me," she said, her eyes filled with tears, "do forgive me; it's too much for my nerves...."

"Don't apologize, madame," said the young man, gently, in a voice free from resentment. "I warned you that my story was laughable; I, better than any one, know how absurd, how nonsensical it is. Yes, the whole thing is perfectly grotesque. But believe me when I tell you that it was no fun in reality. It seems a humorous situation and it remains humorous by the force of circumstances; but it is also horrible. You can see that for yourself, can't you? The two mothers, neither of whom was certain of being a mother, but neither of whom was certain that she was not one, both clung to Jean Louis. He might be a stranger; on the other hand, he might be their own flesh and blood. They loved him to excess and fought for him furiously. And, above all, they both came to hate each other with a deadly hatred. Differing completely in character and education and obliged to live together because neither was willing to forego the advantage of her possible maternity, they lived the life of irreconcilable enemies who can never lay their weapons aside.... I grew up in the midst of this hatred and had it instilled into me by both of them. When my childish heart, hungering for affection, inclined me to one of them, the other would seek to inspire me with loathing and contempt for her. In this manor-house, which they bought on the old doctor's death and to which they added the two wings, I was the involuntary torturer and their daily victim. Tormented as a child, and, as a young man, leading the most hideous of lives, I doubt if any one on earth ever suffered more than I did."

"You ought to have left them!" exclaimed Hortense, who had stopped laughing.

"One can't leave one's mother; and one of those two women was my mother. And a woman can't abandon her son; and each of them was entitled to believe that I was her son. We were all three chained together like convicts, with chains of sorrow, compassion, doubt and also of hope that the truth might one day become apparent. And here we still are, all three, insulting one another and blaming one another for our wasted lives. Oh, what a hell! And there was no escaping it. I tried often enough ... but in vain. The broken bonds became tied again. Only this summer, under the stimulus of my love for Genevi�ve, I tried to free myself and did my utmost to persuade the two women whom I call mother. And then ... and then! I was up against their complaints, their immediate hatred of the wife, of the stranger, whom I was proposing to force upon them.... I gave way. What sort of a life would Genevi�ve have had here, between Madame d'Imbleval and Madame Vaurois? I had no right to victimize her."

Jean Louis, who had been gradually becoming excited, uttered these last words in a firm voice, as though he would have wished his conduct to be ascribed to conscientious motives and a sense of duty. In reality, as R�nine and Hortense clearly saw, his was an unusually weak nature, incapable of reacting against a ridiculous position from which he had suffered ever since he was a child and which he had come to look upon as final and irremediable. He endured it as a man bears a cross which he has no right to cast aside; and at the same time he was ashamed of it. He had never spoken of it to Genevi�ve, from dread of ridicule; and afterwards, on returning to his prison, he had remained there out of habit and weakness.

He sat down to a writing-table and quickly wrote a letter which he handed to R�nine:

"Would you be kind enough to give this note to Mlle. Aymard and beg her once more to forgive me?"

R�nine did not move and, when the other pressed the letter upon him, he took it and tore it up.

"What does this mean?" asked the young man.

"It means that I will not charge myself with any message."

"Why?"

"Because you are coming with us."

"I?"

"Yes. You will see Mlle. Aymard to-morrow and ask for her hand in marriage."

Jean Louis looked at R�nine with a rather disdainful air, as though he were thinking:

"Here's a man who has not understood a word of what I've been explaining to him."

But Hortense went up to R�nine:

"Why do you say that?"

"Because it will be as I say."

"But you must have your reasons?"

"One only; but it will be enough, provided this gentleman is so kind as to help me in my enquiries."

"Enquiries? With what object?" asked the young man.

"With the object of proving that your story is not quite accurate."

Jean Louis took umbrage at this:

"I must ask you to believe, monsieur, that I have not said a word which is not the exact truth."

"I expressed myself badly," said R�nine, with great kindliness. "Certainly you have not said a word that does not agree with what you believe to be the exact truth. But

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)