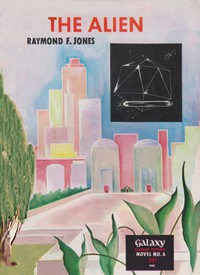

The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖». Author Raymond F. Jones

As Underwood and Phyfe moved to the navigator's table to check their course and that of the pursuing fleet, he said, "I wonder how they spotted us. Our echo screen couldn't have broken down. It must have been sheer astronomical luck that put them on our trail."

Lieutenant Wilson, the navigator, frowned as he pointed to their course charts. "I don't believe that fleet is following us," he said. "If they are, they're going the long way around, because their course at present is heading more than fourteen degrees from ours."

Phyfe and Underwood studied the trajectories, projecting them into space, estimating the rate at which the fleet would approach, considering its superior velocity and the divergent courses.

"It's easy enough to determine whether they're following or not," said Underwood. "We could simply change our own course by ninety degrees. Perhaps they haven't detected us after all, but are merely shooting blind in the general direction we might be, based only on the observations of the police as we took off. In that case, they may hope merely to approach near enough to obtain adequate radar echoes."

Dreyer had heard the news over the interphone and came into the navigation cell. He overheard Underwood's last statement.

"Demarzule would not send out a mere fishing expedition," he said flatly.

"Then what's the answer?" Underwood asked, but in his own mind he was evolving a wild theory. He wondered if Dreyer would confirm it.

"If we were merely going blindly into space to escape, Demarzule would have no concern with us, but if we were going to a destination where our arrival would be malevolent to him—then he would be concerned."

Underwood's eyes lighted. He read in Dreyer's face the same conclusions he had reached.

"And Demarzule would send his fleet not after us particularly, but to that destination to see that we didn't reach it. Therefore, this fleet is headed for the Dragboran world!"

"Not so fast!" Phyfe objected. "Demarzule would be assuming that we know where it is. He has no basis for such an assumption."

Dreyer shook his head. "He doesn't know whether we know the way or not. He knows only that it must be guarded from any possible exploitation by us. If we don't go there, we are no menace to him. If we do, the fleet is there to take care of us."

Phyfe considered, then slowly nodded. "You're right."

"And Demarzule is going to show us the way to the Dragboran weapon!" said Underwood fiercely.

CHAPTER ELEVENThe course was changed so that the flight of the Lavoisier paralleled that of the Terrestrian fleet. The acceleration was increased to a twenty per cent overload of the inertia units, making it necessary for each man to use a small carrier unit against his own increased weight.

Still the fleet crept up, lessening the distance between them, but Underwood felt confident that the distance between their parallel courses was great enough to prevent detection by any means the fleet could mount.

There was new life in the ship as the working and sleeping periods passed rapidly. It was easier to concentrate on their work now that everyone felt he was heading toward a definite goal—they dared not doubt that that goal would yield what they hoped from it.

Under Phyfe's direction, daily classes in Sirenian culture were held. Every fact of existence they tried to view from the Sirenian viewpoint and anticipate its semantic significance to that ancient conquering race.

The trip was estimated at approximately three months. A little impromptu party was held when the fleet passed them near the halfway mark. From then on it was a desperate race to see that the other ships didn't get out of range of the instruments of the Lavoisier.

In the last week of the third month, a sudden, sharp deceleration was observed in the ships of the battle fleet. Underwood alerted his entire crew. If their deductions had been right, they were within a few hundred thousand light years of the Dragboran world.

As the Lavoisier braked some of its tremendous velocity by the opening of the entropy dissipators, the fleet appeared heading for a small galaxy with a group of yellow stars near its outer rim.

Underwood allowed their ship to close somewhat the enormous gap between them and the enemy, but he wanted to maintain a reasonable distance, for the fleet would certainly begin to sweep-search the skies of the alien planet when they arrived and found the Lavoisier had not landed.

The fleet was finally observed to close in upon one of the yellow suns which had a system of five planets. It was the fourth planet toward which the fleet drove. Underwood watched six of the twenty ships land upon it.

"Let's line up behind one of the other planets," he instructed Dawson. "The second appears closest. Then we can swing over and come in behind the moon of number four. We'll probably land on that moon and look the fleet over before deciding our next action."

The only disadvantage in the maneuver was that they could not keep a sufficiently close check on the fleet. They came out of the shadow of the planet for two hours and then were eclipsed by the moon of the fourth planet. During that interval they were in the light of the sun, and they saw no evidence of the fleet at all. The photographers busied themselves with taking pictures of the Dragboran world.

Like the second planet, the moon appeared to be a barren sphere at first glance, but as they approached and moved farther around its six-thousand-mile circumference, they found an area of lush vegetation occupying about an eighth of the surface.

It was the night side at the moment of their approach. No sign of habitation was apparent, though Underwood thought for an instant he glimpsed a smoke column spiraling upward in the night as they dropped to the surface. Then it was gone, and he was not sure that he had really seen anything.

The Lavoisier came to rest on the grassy floor of a clearing in the vegetated corner of the otherwise barren world.

At that instant Mason came into the control room. "I don't know what you expect to find on that planet down there," he said. He handed a batch of photos to Underwood. "We must have pulled a boner somewhere."

Underwood felt a sting of apprehension. "Why? What's the matter?"

"If there's any habitation there, it's under bottles. There isn't a speck of atmosphere on the whole planet."

"That makes it definitely an archeological problem, then," Phyfe said. "It was too much to hope that an advanced civilization like the Dragboran could have existed another half million years. But the photos—what do they show?"

He glanced over Underwood's arm. "There are cities! No question that the planet was once inhabited. But it looks as if it had only been yesterday that those cities had been occupied!"

"That would be explained by the absence of atmosphere," said Underwood. "The cities would not be buried under drifted mounds in an airless world. Some great cataclysm must have removed both atmosphere and life from the planet at the same time. Perhaps our problem is easier, rather than more difficult, because of this. If the destruction occurred reasonably soon after the Dragbora defeated the Sirenians, there may be ample evidence of their weapons among the ruins."

As Dreyer, Terry, and Illia drifted into the control room after the landing, an impromptu war council was held.

"We'll have to wait until the fleet gives up and goes back," said Terry. "We can't hope to go in and blast them out of the way."

"How do we know they'll give up?" asked Illia. "They may be a permanent guard."

"We don't know what they will do," said Underwood. "They might stay for months, anyway, and that is too long for us to wait. Even twenty ships are not a large force on a planet of that size. My plan is to make a night landing in some barren area, then advance slowly up to one of the larger cities and hide the ship. We can make explorations by means of scooter to determine if any of the fleet is in the city. If so, we can move on; if not, we can begin searching. It makes no difference where we begin until we get some kind of idea of the history and culture of the Dragbora."

"It's so hopeless!" Phyfe shook his head fiercely. "It would be a project for a thousand archeologists for a hundred years to examine and analyze such ruins as those down there, yet a hundred of us propose to do it in weeks—hiding from a deadly enemy at the same time! It's utterly impossible."

"I don't think so," said Underwood. "We are searching only for one thing. We know it is a weapon. It is not unreasonable to believe there might be wide reference to it in the writings and history of the Dragbora, since it was the means of destroying their rival empire. The only real difficulty is with the fleet, but I think we can work under their noses for a long enough time."

"You're an incurable optimist," said Terry.

"So are the rest of you, or you'd never have come on this trip."

"I'm agreeable," said Illia. "There's only one thing I'd like to suggest. If this moon is at all habitable, I think we should take a day or two off and stretch our legs outside in some sunshine."

There was no objection to that.

Dawn on the moon of the Dragboran world almost corresponded with the end of their sleeping period. Analysis was made of conditions outside. The atmosphere proved suitable, though thin. The outside temperature appeared high, as was expected from their proximity to the sun.

Then, as Underwood ordered the force shell lifted and opened the port, he received a shock of surprise that made him exclaim aloud. Illia, not far behind, came running.

"What is it, Del?"

His finger was pointing down toward a group of figures at the base of the ship. They were quite human in appearance—in the same way that Demarzule had been. Taller than the Earthmen, and copper-skinned, they watched the opening of the port and bowed low before Underwood and Illia.

There were four of them standing, and they were grouped about a fifth figure lying on a litter.

"Maybe we ought to forget about leaving the ship," said Underwood doubtfully. "There's no use getting tangled up with superstitious natives. We haven't time for that."

"No, wait, Del. That one on the litter is hurt," said Illia. "I believe they've brought him here to see us. Maybe we can do something for him."

Underwood knew it was no use trying to oppose her desire to help. He said, "Let's get Dreyer. He may be able to talk with them."

Dreyer and Phyfe and Nichols were already coming toward the port together. They were excited by Underwood's report.

"This may be an offshoot of either the Dragboran or Sirenian civilization," said Phyfe. "In either case we may find something useful to us."

"They think we're gods. They want us to cure one of their injured," said Underwood. "We can't hope for anything useful in a society as primitive as that."

The semanticists looked out at the small group. Suddenly, Dreyer uttered sounds that resembled a series of grunts with changing inflections. One of the natives, a woman, rose and presented a long speech wholly meaningless to Underwood. But Dreyer stood with strained attention, as if comprehending with difficulty every meaning in that alien tongue.

Then Underwood recalled hearing of Dreyer's statement that a true semanticist should be able to understand and converse in any alien language the first time he heard it. In all languages there are sounds and intonations that have fundamental and identical semantic content. These, Dreyer asserted, could be identified and used in reconstructing the language in a ready flow of conversation if one were skillful enough. Underwood had always believed it was nothing but a boast, but now he was seeing it in action.

The two women of the group and one of the men seemed utterly lost in their attitude of worship, but the other figure, standing a little apart, seemed almost rebellious in appearance. He spoke abruptly and at little length.

"That fellow is a healthy skeptic," said Dreyer. "He's willing to accept us as gods, but he wants proof that we are. He's liable to play tricks to find out."

"We can't bother with them," said Underwood. "There's nothing here for us."

"There may be," said Dreyer. "We should let Illia see what she can do."

Underwood did not press his protests. He allowed Dreyer to direct the natives to bring their companion into the ship. There, in the surgery, Illia examined the injuries. The injured one appeared aged, but there was a quality of joyousness

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)