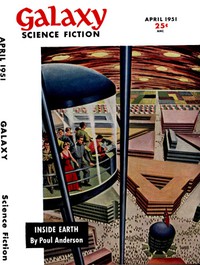

Inside Earth by Poul Anderson (reading tree .TXT) 📖

- Author: Poul Anderson

Book online «Inside Earth by Poul Anderson (reading tree .TXT) 📖». Author Poul Anderson

"Right," said the Coordinator. "We'll give them the ammunition for their propaganda. We've been doing it. Result: the leaders get mad. Races, religions, nationalities, they hate us worse than they hate each other."

The way he painted it, I was hardly needed at all. I told him that.

"Ideally, that would be the situation, Conru. Only it doesn't work that way." He took out a soft cloth and wiped his forehead. "Even the leaders are too involved in this myth of differences and they can't concentrate all their efforts. Luron, of course, would be the other alternative—"

That was a very logical statement, but sometimes logic has a way of making you laugh, and I was laughing now. Luron considered itself our arch-enemy. With a few dozen allies on a path of conquest, Luron thought it could wrest Empire from our hands. Well, we let them play. And each time Luron swooped down on one of the more primitive planets, we let them, for Luron would serve as well as ourselves in goading backward peoples to unite and advance. Perhaps Luron, as a social entity, grew wiser each time. Certainly the primitive colonials did. Luron had started a chain reaction which threatened to overthrow the tyranny of superstition on a hundred planets. Good old Luron, our arch-enemy, would see the light itself some day.

The Coordinator shook his head. "Can't use Luron here. Technologies are entirely too similar. It might shatter both planets, and we wouldn't want that."

"So what do we use?"

"You, Conru. You get in with the revolutionaries, you make sure that they want to fight, you—"

"I see," I told him. "Then I try to stop it at the last minute. Not so soon that the rebellion doesn't help at all—"

The Coordinator put his hand down flat. "Nothing of the sort. They must fight. And they must be defeated, again and again, if necessary, until they are ready to succeed. That will be, of course, when they are totally against us."

I stood up. "I understand."

He waved me back into the chair. "You'll be lucky to understand it by the time you're finished with this assignment and transferred to another ... that is, if you come out of this one alive."

I smiled a bit sheepishly and told him to go ahead.

"We have some influence in the underground movement, as you might logically expect. The leader is a man we worked very hard to have elected."

"A member of one of the despised races?" I guessed.

"The best we could do at this point was to help elect someone from a minority sub-group of the dominant white race. The leader's name is Levinsohn. He is of the white sub-group known as Jews."

"How well is this Levinsohn accepted by the movement?"

"Considerable resistance and hostility," the Coordinator said. "That's to be expected. However, we've made sure that there is no other organization the minority-haters can join, so they have to follow him or quit. He's able, all right; one of the most able men they have, which helps our aims. Even those who discriminate against Jews reluctantly admire him. He's moved the headquarters of the movement out into space, and the man's so brilliant that we don't even know where. We'll find out, mainly through you, I hope, but that isn't the important thing."

"What is?" I asked, baffled.

"To report on the unification of Earth. It's possible that the anarch movement can achieve it under Levinsohn. In that case, we'll make sure they win, or think they win, and will gladly sign a treaty giving Earth equal planetary status in the Empire."

"And if unity hasn't been achieved?"

"We simply crush this rebellion and make them start all over again. They'll have learned some degree of unity from this revolt and so the next one will be more successful." He stood up and I got out of my chair to face him. "That's for the future, though. We'll work out our plans from the results of this campaign."

"But isn't there a lot of danger in the policy of fomenting rebellion against us?" I asked.

He lifted his shoulders. "Evolution is always painful, forced evolution even more so. Yes, there are great dangers, but advance information from you and other agents can reduce the risk. It's a chance we must take, Conru."

"Conrad," I corrected him, smiling. "Plain Mr. Conrad Haugen ... of Earth."

II

A few days later, I left North America Center, and in spite of the ominous need to hurry, my eastward journey was a ramble. The anarchs would be sure to check my movements as far back as they could, and my story had better ring true. For the present, I must be my role, a vagabond.

The city was soon behind me. It was far from other settlement—it is good policy to keep the Centers rather isolated, and we could always contact our garrisons in native towns quickly enough. Before long I was alone in the mountains.

I liked that part of the trip. The Rockies are huge and serene, a fresh cold wind blows from their peaks and roars in the pines, brawling rivers foam through their dales and canyons—it is a big landscape, clean and strong and lonely. It speaks with silence.

I hitched a ride for some hundreds of miles with one of the great truck-trains that dominate the western highways. The driver was Earthling, and though he complained much about the Valgolian tyranny he looked well-fed, healthy, secure. I thought of the wars which had been laying the planet waste, the social ruin and economic collapse which the Empire had mended, and wondered if Terra would ever be fit to rule itself.

I came out of the enormous mountainlands into the sage plains of Nevada. For a few days I worked at a native ranch, listening to the talk and keeping my mouth shut. Yes, there was discontent!

"Their taxes are killing me," said the owner. "What the hell incentive do I have to produce if they take it away from me?" I nodded, but thought: Your kind was paying more taxes in the old days, and had less to show for it. Here you get your money back in public works and universal security. No one on Earth is cold or hungry. Can you only produce for your own private gain, Earthling?

"The labor draft got my kid the other day," said the foreman. "He'll spend two good years of his life working for them, and prob'ly come back hopheaded about the good o' the Empire."

There was a time, I thought, when millions of Earthlings clamored for work, or spent years fighting their wars, gave their youth to a god of battle who only clamored for more blood. And how can we have a stable society without educating its members to respect it?

"I want another kid," said the female cook. "Two ain't really enough. They're good boys, but I want a girl too. Only the Eridanian law says if I go over my quota, if I have one more, they'll sterilize me! And they'd do it, the meddling devils."

A billion Earthlings are all the Solar System can hold under decent standards of living without exhausting what natural resources their own culture left us, I thought. We aren't ready to permit emigration; our own people must come first. But these beings can live well here. Only now that we've eliminated famine, plague, and war, they'd breed beyond reason, breed till all the old evils came back to throttle them, if we didn't have strict population control.

"Yeah," said her husband bitterly. "They never even let my cousin have kids. Sterilized him damn near right after he was born."

Then he's a moron, or carries hemophilia, or has some other hereditary taint, I thought. Can't they see we're doing it for their own good? It costs us fantastically in money and trouble, but the goal is a level of health and sanity such as this race never in its history dreamed possible.

"They're stranglin' faith," muttered someone else.

Anyone in the Empire may worship as he chooses, but should permission be granted to preach demonstrable falsehoods, archaic superstitions, or antisocial nonsense? The old "free" Earth was not noted for liberalism.

"We want to be free."

Free? Free for what? To loose the thousand Earthly races and creeds and nationalisms on each other—and on the Galaxy—to wallow in barbarism and slaughter and misery as before we came? To let our works and culture be thrown in the dust, the labor of a century be demolished, not because it is good or bad but simply because it is Valgolian? Epsilon Eridanian!

"We'll be free. Not too long to wait, either—"

That's up to nobody else but you!

I couldn't get much specific information, but then I hadn't expected to. I collected my pay and drifted on eastward, talking to people of all classes—farmers, mechanics, shopowners, tramps, and such data as I gathered tallied with those of Intelligence.

About twenty-five per cent of the population, in North America at least—it was higher in the Orient and Africa—was satisfied with the Imperium, felt they were better off than they would have been in the old days. "The Eridanians are pretty decent, on the whole. Some of 'em come in here and act nice and human as you please."

Some fifty per cent was vaguely dissatisfied, wanted "freedom" without troubling to define the term, didn't like the taxes or the labor draft or the enforced disarmament or the legal and social superiority of Valgolians or some such thing, had perhaps suffered in the reconquest. But this group constituted no real threat. It would tend to be passive whatever happened. Its greatest contribution would be sporadic rioting.

The remaining twenty-five per cent was bitter, waiting its chance, muttering of a day of revenge—and some portion of this segment was spreading propaganda, secretly manufacturing and distributing weapons, engaging in clandestine military drill, and maintaining contact with the shadowy Legion of Freedom.

Childish, melodramatic name! But it had been well chosen to appeal to a certain type of mind. The real, organized core of the anarch movement was highly efficient. In those months I spent wandering and waiting, its activities mounted almost daily.

The illegal radio carried unending programs, propaganda, fabricated stories of Valgolian brutality. I knew from personal experience that some were false, and I knew the whole Imperial system well enough to spot most of the rest at least partly invented. I realized we couldn't trace such a well-organized setup of mobile and coordinated units, and jamming would have been poor tactics, but even so—

The day is coming.... Earthmen, free men, be ready to throw off your shackles.... Stand by for freedom!

I stuck to my role. When autumn came, I drifted into one of the native cities, New Chicago, a warren of buildings near the remains of the old settlement, the same gigantic slum that its predecessor had been. I got a room in a cheap hotel and a job in a steel mill.

I was Conrad Haugen, Norwegian-American, assigned to a spaceship by the labor draft and liking it well enough to re-enlist when my term was up. I had wandered through much of the Empire and had had a great deal of contact with Eridanians, but was most emphatically not a Terrie. In fact, I thought it would be well if the redskin yoke could be thrown off, both because of liberty and the good pickings to be had in the Galaxy if the Empire should collapse. I had risen to second mate on an interstellar tramp, but could get no further because of the law that the two highest officers must be Valgolian. That had embittered me and I returned to Earth, foot-loose and looking for trouble.

I found it. With officer's training and the strength due to a home planet with a gravity half again that of Earth, I had no difficulty at all becoming a foreman. There was a big fellow named Mike Riley who thought he was entitled to the job. We settled it behind a shed, with the workmen looking on, and I beat him unconscious as fast as possible. The raw, sweating savagery of it made me feel ill inside. They'd let this loose among the stars!

After that I was one of the boys and Riley was my best friend. We went out together, wenching and drinking, raising hell in the cold dirty canyons of steel and stone which the natives called streets. Valgolia, Valgolia, the clean bare windswept heights of your mountains, soughing trees and thunderous waters and Maara waiting for me to come home! Riley often proposed that we find an Eridanian and beat him to death, and I would agree, hiccupping, because I knew they didn't go alone into native quarters any

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)