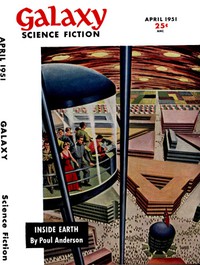

Inside Earth by Poul Anderson (reading tree .TXT) 📖

- Author: Poul Anderson

Book online «Inside Earth by Poul Anderson (reading tree .TXT) 📖». Author Poul Anderson

Save for the spaceport and other installations, Main Base was underground. There was no city to relieve the grimness of the scene. We were in a narrow valley between sheer, ragged cliffs that soared crazily into a murky sky. The sun was low, a smouldering disc of dull red like curdling blood; its sullen light glimmered on the undying snow and ice and seemed only to make the land darker. Stars glittered here and there in the dusky heavens, hard and bright and cruel, almost, as in space.

Dark sky, dark land, dark world, with the sheer terrible mountains climbing gauntly for the upper gloom, crags and glaciers like fangs against the dizzy cliffs, with the great shadows marching across the bloody snow toward us, with a crazed wind muttering and whining and chewing at our flesh. It was cold. The cold was like a knife. Pain stung with every breath and eyes watered with tears that froze on suddenly numb cheeks. A great shudder ripped through us and we ran toward the entrance to the city. The snow crunched dry and old under our boots, the cold ate up through the soles, and the wind whistled its scorn.

Even when an elevator had taken us a mile down into the warmth and light of the base, we could not forget. It was a city for a million men and other beings and more than a few women and children, a city of long streets and small neat apartments, hydroponic farms and food synthesizers, schools, shops and amusement places, factories, military barracks and arsenals, even an occasional little flower garden. Its people could live here almost indefinitely, working and waiting for their day of rising.

There was little formality in the civilian areas. Everyone who had come this far was trusted. A man came up to us new arrivals from Earth, asked about conditions there, and then said he would show us to our quarters. Later we would be told to whom we should report for duty.

"Let's go, then, Con," said Barbara, and slipped a cool little hand into mine. I could not refrain from casting a smug backward glance at the somewhat chapfallen Kane.

V

We slipped quickly into the routine of the place. It was a taut-nerved, hard-working daily round. I could feel the savage expectancy building up like a physical force, but intelligent life is adaptable and we got used to it. There was work to do.

Hawkins was second in command of the psychological service, testing and screening and treating personnel, working on training and indoctrination, and with a voice in the general staff where problems of unit coordination and psychological warfare were concerned. Barbara worked under him, secretary and records keeper and general trouble-shooter. Those were high posts, but both were allowed to retain the nominally civilian status which they preferred.

Their influence and my own test scores got me appointed assistant supervisor of the shipyards. That suited me very well—I was reasonably free from direct orders and discipline, with authority to come and go pretty much as I pleased. They kept me busy; sometimes I worked the clock around, and I did my best to further production of the weapons which might destroy my planet. For whatever I did would make little difference at this late date.

A good deal of my time also went to drill with the armed forces of which, like every able-bodied younger man, I was a reserve member. They put me in an engineer unit and I soon had command of it. I did my best here too, whipping my grim young charges into a sapper group comparable to the Empire's, for I had to be above all suspicion, even of incompetence.

We worked at our learning. We went topside and shivered and manned our guns, set our mines and threw up our bridges, in the racking cold of Boreas. Over ancient snow and ice we trotted, lost in the jumbled wilderness of cruel peaks and railing wind, peeling the skin from our fingers when we touched metal, camped under scornful stars and a lash of drifting ice-dust—but we learned!

My own, more private education went on apace. I found where we were. It was a forgotten red dwarf star out near the shadowy border of the Empire, listed in the catalogues as having one Class III planet of no interest or value. That was a good choice; no spaceship would ever happen into this system by accident or exploration. The anarchs had built their hopes on the one lonely planet, and had named it Boreas after the god of the north wind in one of their mythologies. My company called it less complimentary things.

The base, including the attached city, was under military command which ultimately led up to the general staff of the Legion. This was a council of officers from half a score of rebellious planets, though Earthlings predominated and, of course, Simon Levinsohn held the supreme authority. I met him a few times, a gaunt, lonely man, enormously able, ridden by his cause as by a nightmare, but not unkindly on a personal level. With just that indomitable heart, the Maccabees had faced Rome's iron legions—Valgolia was greatly interested in the ancient history of a conquered province, knowing how often it held the key to current problems.

There was also a liaison officer from Luron sitting at staff meetings. Luron!

When I first saw him, this Colonel Wergil, I stood stiff and cold and felt the bristling along my spine. He looked as humanoid as most of the races at the base. Hairless, faintly scaled greenish-yellow skin, six fingers to a hand, and flat chinless face don't make that breed hideous to me; I have reckoned Ganolons and Mergri among my friends. But Luron—the old and deadly rival, the lesser empire watching its chance to pounce on us, hating us for the check we are on the ambitions of their militarists, Luron.

I have no race prejudices and am willing to take the word of our comparative psychologists that there is no more inherent evil in the Luronians than in any other stock, that the peculiar cold viciousness of their civilization is a matter of unfortunate cultural rather than biological evolution and could be changed in time. But none of this alters the fact that at present they are what they are, brilliant, greedy, heartless, and a menace to the peace of the Galaxy. I have been too long engaged in the struggle between my nation and theirs to think otherwise.

Other states had sent some clandestine help to the Legion, weapons and money and vague promises. Luron, I soon found, had said it would attack us in full strength if the uprising showed a good chance of success, and meanwhile, they gave assistance, credits and materiel and the still more important machine tools, and Wergil's military advice was useful.

I know now, as I suspected even then, that Levinsohn and his associates were not fooled as to Luron's ultimate intentions. Indeed, they planned to make common cause with what remained of Valgolia, as well as certain other traditional foes of their present ally, as soon as they had gained their objectives of independence, and stop any threat of aggression from Luron. It was shrewdly planned, but such a shaky coalition, still bleeding with the hurts and hatreds of a struggle just ended, would be weaker than the Empire, and Luron almost certainly would have sowed further dissension in it and waited for its decay before striking.

The Earthlings have a proverb to the effect that he who sups with the Devil must use a long spoon. But they seemed to have forgotten it now.

The attack, I learned, was scheduled for about four months from the time the agents were recalled. The rebels were counting on the Valgolian power being spread too thinly over the Empire to stand off their massed assault on a few key points. Then, with the home planet a radioactive ruin, with revolt in a score of planetary systems and the ensuing chaos and communications breakdown, and with the Luronians invading, the Imperial fleet and military would have to make terms with the anarchs.

It would work. I knew with a dark chill that it would work. Unless somehow I could get a warning out. That had to be done for more than the protection of Epsilon Eridani, which, even in a surprise attack could defend itself better than these conspirators realized. But all bloodshed should be spared, if possible—and the rebellion did not yet deserve to succeed, for the unity achieved thus far had been the unity of a snake pit against a temporary enemy.

Did it all rest on me? God of space, had the whole burden of history suddenly fallen on my shoulders?

I didn't dare think about it. I forced the consequences of failure out of my forebrain, back down into the unconscious, the breeding ground of nightmares, and lived from one day to the next. I worked, and waited, learned what I could and watched for my chance.

But it was not all grimness and concentration. It couldn't be; intelligent life just isn't built that way. We had our social activities, small gatherings or big parties, we relaxed and played. At first I found that gratifying, for it gave me a chance to pump the others. Then I found it maddening, because it kept me from snooping and laying plans. Finally it began to hurt—I was coming to know the anarchs.

They lived and laughed and loved even as humans do. They were basically as decent and reasonable as any similar group of Valgolians. Many were as tormented as I by the thought of the slaughter they readied. There were embittered ones, who had lost all they held dear, and I realized that, while civilization has its price, you can't be objective about it when you are the one who must pay. There were others who had been well off and had chucked all their hopes to join a desperate cause in which they happened to believe. There were children—and what had they done to deserve having their parents gambling away life?

In spite of their appearance, to which I was now accustomed, they were human. When I had laughed and talked and sung and drunk beer and danced and arranged entertainments with them, they were my friends.

Moodily, I began to see that I would be one of the price-payers.

I saw most of Hawkins and Barbara, and after them—because of her—Kane. The old psychologist and I got along famously. He would drop into my room for a smoke and a cup of coffee and a drawled conversation whenever he had the chance. His slow gentle voice, his trenchancy, the way the little crinkles appeared around his eyes when he smiled, reminded me of my father. I often wish those two could have met. They would have enjoyed each other.

Then Barbara would stop by on her way from work, or, better yet, she would ask me over to her apartment for a home-cooked dinner. Yes, she could cook too. We would sometimes take long walks down the corridors of the city, we even went up once in a while to the surface for a breath of cold air and loneliness, and it was the most natural thing in the world for us to go hand in hand.

There was no sunlight underground. But when the fluorotube glow shone on her hair, I thought of sunlight on Earth, the high keen light of the Colorado plateaus, the morning light stealing through the trees of Hood Island.

Ydis, Ydis, I said, once your violet eyes were like the skies over Kalariho, over Kealvigh, our home, pasture land of winds. But it has been so long. It has been ten years since you died—

I fought. May all the gods bear witness that I fought myself. And I thought I was winning.

VI

I will never forget one certain evening.

Hawkins and I had come over to Barbara's for supper, and the three of us were sitting now, talking. Wieniawski's Violin Concerto cried its sorrow, muted in the background, and the serene home she had made of the bare little functional apartment folded itself around us. Then Kane dropped in as he often did, with a casualness that fooled nobody, and sat with all his soul in his eyes, looking at Barbara. He was a nice kid. I didn't know why he should annoy me so.

The talk shifted to Valgolia. I found myself taking the side of my race. It wasn't that I hoped to convert anyone, but—well, it was wrong that we should be monsters in the sight of these friends.

"Brutes," said Kane. "Two-legged animals.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)