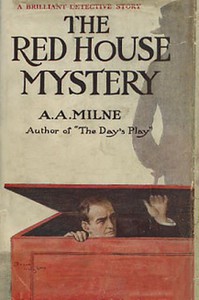

The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖

- Author: A. A. Milne

Book online «The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖». Author A. A. Milne

“You’re quite right. Well?”

“Well, then, this clothes business. Doesn’t that seem rather to bear out the escaping theory? Mark’s brown suit was known to the police. Couldn’t Cayley have brought him another one in the passage, to escape in, and then have had the brown one on his hands? And thought it safest to hide it in the pond?”

“Yes,” said Anthony thoughtfully. Then: “Go on.”

Bill went on eagerly:

“It all seems to fit in, you know. I mean even with your first theory—that Mark killed him accidentally and then came to Cayley for help. Of course, if Cayley had played fair, he’d have told Mark that he had nothing to be afraid of. But he isn’t playing fair; he wants to get Mark out of the way because of the girl. Well, this is his chance. He makes Mark as frightened as possible, and tells him that his only hope is to run away. Well, naturally, he does all he can to get him well away, because if Mark is caught, the whole story of Cayley’s treachery comes out.”

“Yes. But isn’t it overdoing it rather to make him change his underclothes and everything? It wastes a good deal of time, you know.”

Bill was pulled up short, and said, “Oh!” in great disappointment.

“No, it’s not as bad as that, Bill,” said Antony with a smile. “I daresay the underclothes could be explained. But here’s the difficulty. Why did Mark need to change from brown to blue, or whatever it was, when Cayley was the only person who saw him in brown?”

“The police description of him says that he is in a brown suit.”

“Yes, because Cayley told the police. You see, even if Mark had had lunch in his brown suit, and the servants had noticed it, Cayley could always have pretended that he had changed into blue after lunch, because only Cayley saw him afterwards. So if Cayley had told the Inspector that he was wearing blue, Mark could have escaped quite comfortably in his brown, without needing to change at all.”

“But that’s just what he did do,” cried Bill triumphantly. “What fools we are!”

Antony looked at him in surprise, and then shook his head.

“Yes, yes!” insisted Bill. “Of course! Don’t you see? Mark did change after lunch, and, to give him more of a chance of getting away, Cayley lied and said that he was wearing the brown suit in which the servants had seen him. Well, then he was afraid that the police might examine Mark’s clothes and find the brown suit still there, so he hid it, and then dropped it in the pond afterwards.”

He turned eagerly to his friend, but Antony said nothing. Bill began to speak again, and was promptly waved into silence.

“Don’t say anything more, old boy; you’ve given me quite enough to think about. Don’t let’s bother about it to-night. We’ll just have a look at this cupboard and then get to bed.”

But the cupboard had not much to tell them that night. It was empty save for a few old bottles.

“Well, that’s that,” said Bill.

But Antony, on his knees with the torch in his hand, continued to search for something.

“What are you looking for?” asked Bill at last.

“Something that isn’t there,” said Antony, getting up and dusting his trousers. And he locked the door again.

Guess-work

The inquest was at three o’clock; thereafter Antony could have no claim on the hospitality of the Red House. By ten o’clock his bag was packed, and waiting to be taken to ‘The George.’ To Bill, coming upstairs after a more prolonged breakfast, this early morning bustle was a little surprising.

“What’s the hurry?” he asked.

“None. But we don’t want to come back here after the inquest. Get your packing over now and then we can have the morning to ourselves.”

“Righto.” He turned to go to his room, and then came back again. “I say, are we going to tell Cayley that we’re staying at ‘The George’?”

“You’re not staying at ‘The George,’ Bill. Not officially. You’re going back to London.”

“Oh!”

“Yes. Ask Cayley to have your luggage sent in to Stanton, ready for you when you catch a train there after the inquest. You can tell him that you’ve got to see the Bishop of London at once. The fact that you are hurrying back to London to be confirmed will make it seem more natural that I should resume my interrupted solitude at ‘The George’ as soon as you have gone.”

“Then where do I sleep to-night?”

“Officially, I suppose, in Fulham Place; unofficially, I suspect, in my bed, unless they’ve got another spare room at ‘The George.’ I’ve put your confirmation robe—I mean your pyjamas and brushes and things—in my bag, ready for you. Is there anything else you want to know? No? Then go and pack. And meet me at ten-thirty beneath the blasted oak or in the hall or somewhere. I want to talk and talk and talk, and I must have my Watson.”

“Good,” said Bill, and went off to his room.

An hour later, having communicated their official plans to Cayley, they wandered out together into the park.

“Well?” said Bill, as they sat down underneath a convenient tree. “Talk away.”

“I had many bright thoughts in my bath this morning,” began Antony. “The brightest one of all was that we were being damn fools, and working at this thing from the wrong end altogether.”

“Well, that’s helpful.”

“Of course it’s very hampering being a detective, when you don’t know anything about detecting, and when nobody knows that you’re doing detection, and you can’t have people up to cross-examine them, and you have neither the energy nor the means to make proper inquiries; and, in short, when you’re doing the whole thing in a thoroughly amateur, haphazard way.”

“For amateurs I don’t think we’re doing at all badly,” protested Bill.

“No; not for amateurs. But if we had been professionals, I believe we should have gone at it from the other end. The Robert end. We’ve been wondering about Mark and Cayley all the time. Now let’s wonder about Robert for a bit.”

“We know so little about him.”

“Well, let’s see what we do know. First of all, then, we know vaguely that he was a bad lot—the sort of brother who is hushed up in front of other people.”

“Yes.”

“We know that he announced his approaching arrival to Mark in a rather unpleasant letter, which I have in my pocket.”

“Yes.”

“And then we know rather a curious thing. We know that Mark told you all that this black sheep was coming. Now, why did he tell you?”

Bill was thoughtful for a moment.

“I suppose,” he said slowly, “that he knew we were bound to see him, and thought that the best way was to be quite frank about him.”

“But were you bound to see him? You were all away playing golf.”

“We were bound to see him if he stayed in the house that night.”

“Very well, then. That’s one thing we’ve discovered. Mark knew that Robert was staying in the house that night. Or shall we put it this way—he knew that there was no chance of getting Robert out of the house at once.”

Bill looked at his friend eagerly.

“Go on,” he said. “This is getting interesting.”

“He also knew something else,” went on Antony. “He knew that Robert was bound to betray his real character to you as soon as you met him. He couldn’t pass him off on you as just a travelled brother from the Dominions, with perhaps a bit of an accent; he had to tell you at once, because you were bound to find out, that Robert was a wastrel.”

“Yes. That’s sound enough.”

“Well, now, doesn’t it strike you that Mark made up his mind about all that rather quickly?”

“How do you mean?”

“He got this letter at breakfast. He read it; and directly he had read it he began to confide in you all. That is to say, in about one second he thought out the whole business and came to a decision—to two decisions. He considered the possibility of getting Robert out of the way before you came back, and decided that it was impossible. He considered the possibility of Robert’s behaving like an ordinary decent person in public, and decided that it was very unlikely. He came to those two decisions instantaneously, as he was reading the letter. Isn’t that rather quick work?”

“Well, what’s the explanation?”

Antony waited until he had refilled and lighted his pipe before answering.

“What’s the explanation? Well, let’s leave it for a moment and take another look at the two brothers. In conjunction, this time, with Mrs. Norbury.”

“Mrs. Norbury?” said Bill, surprised.

“Yes. Mark hoped to marry Miss Norbury. Now, if Robert really was a blot upon the family honour, Mark would want to do one of two things. Either keep it from the Norburys altogether, or else, if it had to come out, tell them himself before the news came to them indirectly. Well, he told them. But the funny thing is that he told them the day before Robert’s letter came. Robert came, and was killed, the day before yesterday—Tuesday. Mark told Mrs. Norbury about him on Monday. What do you make of that?”

“Coincidence,” said Bill, after careful thought. “He’d always meant to tell her; his suit was prospering, and just before it was finally settled, he told her. That happened to be Monday. On Tuesday he got Robert’s letter, and felt jolly glad that he’d told her in time.”

“Well, it might be that, but it’s rather a curious coincidence. And here is something which makes it very curious indeed. It only occurred to me in the bath this morning. Inspiring place, a bathroom. Well, it’s this—he told her on Monday morning, on his way to Middleston in the car.”

“Well?”

“Well.”

“Sorry, Tony; I’m dense this morning.”

“In the car, Bill. And how near can the car get to Jallands?”

“About six hundred yards.”

“Yes. And on his way to Middleston, on some business or other, Mark stops the car, walks six hundred yards down the hill to Jallands, says, ‘Oh, by the way, Mrs. Norbury, I don’t think I ever told you that I have a shady brother called Robert,’ walks six hundred yards up the hill again, gets into the car, and goes off to Middleston. Is that likely?”

Bill frowned heavily.

“Yes, but I don’t see what you’re getting at. Likely or not likely, we know he did do it.”

“Of course he did. All I mean is that he must have had some strong reason for telling Mrs. Norbury at once. And the reason I suggest is that he knew on that morning—Monday morning, not Tuesday—that Robert was coming to see him, and had to be in first with the news.

“But—but—”

“And that would explain the other point—his instantaneous decision at breakfast to tell you all about his brother. It wasn’t instantaneous. He knew on Monday that Robert was coming, and decided then that you would all have to know.”

“Then how do you explain the letter?”

“Well, let’s have a look at it.”

Antony took the letter from his pocket and spread it out on the grass between them.

“Mark, your loving brother is coming to see you to-morrow, all the way from Australia. I give you warning, so that you will be able to conceal your surprise but not I hope your pleasure. Expect him at three or thereabouts.”

“No date mentioned, you see,” said Antony. “Just to-morrow.”

“But he got this on Tuesday.”

“Did he?”

“Well, he read it out to us on Tuesday.”

“Oh, yes! he read it out to you.”

Bill read the letter again, and then turned it over and looked at the back of it. The back of it had nothing to say to him.

“What about the postmark?” he asked.

“We haven’t got the envelope, unfortunately.”

“And you think that he got this letter on Monday.”

“I’m inclined to think so, Bill. Anyhow, I think—I feel almost certain—that he knew on Monday that his brother was coming.”

“Is that going to help us much?”

“No. It makes it more difficult. There’s something rather uncanny about it all. I don’t understand it.” He was silent for a little, and then added, “I wonder if the inquest is going to help us.

“What about last night? I’m longing to hear what you make of that. Have you been thinking it out at all?”

“Last night,” said Antony thoughtfully to himself. “Yes, last night wants some explaining.”

Bill waited hopefully for him to explain. What, for instance, had Antony been looking for in the cupboard?

“I think,” began Antony slowly, “that after last night we must give up the idea that Mark has been killed; killed, I mean, by Cayley. I don’t believe anybody would go to so much trouble to hide a suit of clothes when he had a body on his hands.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)