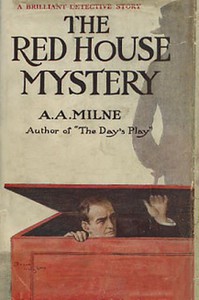

The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖

- Author: A. A. Milne

Book online «The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖». Author A. A. Milne

“My dear Holmes, I am at your service.”

Antony gave him a smile and was silent for a little, thinking.

“Is there another inn at Stanton—fairly close to the station?”

“The ‘Plough and Horses’—just at the corner where the road goes up to the station—is that the one you mean?”

“That would be the one. I suppose you could do with a drink, couldn’t you?”

“Rather!” said Bill, with a grin.

“Good. Then have one at the ‘Plough and Horses.’ Have two, if you like, and talk to the landlord, or landlady, or whoever serves you. I want you to find out if anybody stayed there on Monday night.”

“Robert?” said Bill eagerly.

“I didn’t say Robert,” said Antony, smiling. “I just want you to find out if they had a visitor who slept there on Monday night. A stranger. If so, then any particulars you can get of him, without letting the landlord know that you are interested—”

“Leave it to me,” broke in Bill. “I know just what you want.”

“Don’t assume that it was Robert—or anybody else. Let them describe the man to you. Don’t influence them unconsciously by suggesting that he was short or tall, or anything of that sort. Just get them talking. If it’s the landlord, you’d better stand him a drink or two.”

“Right you are,” said Bill confidently. “Where do I meet you again?”

“Probably at ‘The George.’ If you get there before me, you can order dinner for eight o’clock. Anyhow we’ll meet at eight, if not before.”

“Good.” He nodded to Antony and strode off back to Stanton again.

Antony stood watching him with a little smile at his enthusiasm. Then he looked round slowly, as if in search of something. Suddenly he saw what he wanted. Twenty yards farther on a lane wandered off to the left, and there was a gate a little way up on the right-hand side of it. Antony walked to the gate, filling his pipe as he went. Then he lit his pipe, sat on the gate, and took his head in his hands.

“Now then,” he said to himself, “let’s begin at the beginning.”

It was nearly eight o’clock when William Beverley, the famous sleuth-hound, arrived, tired and dusty, at ‘The George,’ to find Antony, cool and clean, standing bare-headed at the door, waiting for him.

“Is dinner ready?” were Bill’s first words.

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll just have a wash. Lord, I’m tired.”

“I never ought to have asked you,” said Antony penitently.

“That’s all right. I shan’t be a moment.” Half-way up the stairs he turned round and asked, “Am I in your room?”

“Yes. Do you know the way?”

“Yes. Start carving, will you? And order lots of beer.” He disappeared round the top of the staircase. Antony went slowly in.

When the first edge of his appetite had worn off, and he was able to spare a little time between the mouthfuls, Bill gave an account of his adventures. The landlord of the “Plough and Horses” had been sticky, decidedly sticky—Bill had been unable at first to get anything out of him. But Bill had been tactful; lorblessyou, how tactful he had been.

“He kept on about the inquest, and what a queer affair it had been, and so on, and how there’d been an inquest in his wife’s family once, which he seemed rather proud about, and I kept saying, ‘Pretty busy, I suppose, just now, what?’ and then he’d say, ‘Middlin’,’ and go on again about Susan—that was the one that had the inquest—he talked about it as if it were a disease—and then I’d try again, and say, ‘Slack times, I expect, just now, eh?’ and he’d say ‘Middlin’’ again, and then it was time to offer him another drink, and I didn’t seem to be getting much nearer. But I got him at last. I asked him if he knew John Borden—he was the man who said he’d seen Mark at the station. Well, he knew all about Borden, and after he’d told me all about Borden’s wife’s family, and how one of them had been burnt to death—after you with the beer; thanks—well, then I said carelessly that it must be very hard to remember anybody whom you had just seen once, so as to identify him afterwards, and he agreed that it would be ‘middlin’ hard,’ and then—”

“Give me three guesses,” interrupted Antony. “You asked him if he remembered everybody who came to his inn?”

“That’s it. Bright, wasn’t it?”

“Brilliant. And what was the result?”

“The result was a woman.”

“A woman?” said Antony eagerly.

“A woman,” said Bill impressively. “Of course I thought it was going to be Robert—so did you, didn’t you?—but it wasn’t. It was a woman. Came quite late on Monday night in a car—driving herself—went off early next morning.”

“Did he describe her?”

“Yes. She was middlin’. Middlin’ tall, middlin’ age, middlin’ colour, and so on. Doesn’t help much, does it? But still—a woman. Does that upset your theory?”

Antony shook his head.

“No, Bill, not at all,” he said.

“You knew all the time? At least, you guessed?”

“Wait till to-morrow. I’ll tell you everything to-morrow.”

“To-morrow!” said Bill in great disappointment.

“Well, I’ll tell you one thing to-night, if you’ll promise not to ask any more questions. But you probably know it already.”

“What is it?”

“Only that Mark Ablett did not kill his brother.”

“And Cayley did?”

“That’s another question, Bill. However, the answer is that Cayley didn’t, either.”

“Then who on earth—”

“Have some more beer,” said Antony with a smile. And Bill had to be content with that.

They were early to bed that evening, for both of them were tired. Bill slept loudly and defiantly, but Antony lay awake, wondering. What was happening at the Red House now? Perhaps he would hear in the morning; perhaps he would get a letter. He went over the whole story again from the beginning—was there any possibility of a mistake? What would the police do? Would they ever find out? Ought he to have told them? Well, let them find out; it was their job. Surely he couldn’t have made a mistake this time. No good wondering now; he would know definitely in the morning.

In the morning there was a letter for him.

Cayley’s Apology

“My Dear Mr. Gillingham,

“I gather from your letter that you have made certain discoveries which you may feel it your duty to communicate to the police, and that in this case my arrest on a charge of murder would inevitably follow. Why, in these circumstances, you should give me such ample warning of your intentions I do not understand, unless it is that you are not wholly out of sympathy with me. But whether or not you sympathize, at any rate you will want to know—and I want you to know—the exact manner in which Ablett met his death and the reasons which made that death necessary. If the police have to be told anything, I would rather that they too knew the whole story. They, and even you, may call it murder, but by that time I shall be out of the way. Let them call it what they like.

“I must begin by taking you back to a summer day fifteen years ago, when I was a boy of thirteen and Mark a young man of twenty-five. His whole life was make-believe, and just now he was pretending to be a philanthropist. He sat in our little drawing-room, flicking his gloves against the back of his left hand, and my mother, good soul, thought what a noble young gentleman he was, and Philip and I, hastily washed and crammed into collars, stood in front of him, nudging each other and kicking the backs of our heels and cursing him in our hearts for having interrupted our game. He had decided to adopt one of us, kind Cousin Mark. Heaven knows why he chose me. Philip was eleven; two years longer to wait. Perhaps that was why.

“Well, Mark educated me. I went to a public school and to Cambridge, and I became his secretary. Well, much more than his secretary as your friend Beverley perhaps has told you: his land agent, his financial adviser, his courier, his—but this most of all—his audience. Mark could never live alone. There must always be somebody to listen to him. I think in his heart he hoped I should be his Boswell. He told me one day that he had made me his literary executor—poor devil. And he used to write me the absurdest long letters when I was away from him, letters which I read once and then tore up. The futility of the man!

“It was three years ago that Philip got into trouble. He had been hurried through a cheap grammar school and into a London office, and discovered there that there was not much fun to be got in this world on two pounds a week. I had a frantic letter from him one day, saying that he must have a hundred at once, or he would be ruined, and I went to Mark for the money. Only to borrow it, you understand; he gave me a good salary and I could have paid it back in three months. But no. He saw nothing for himself in it, I suppose; no applause, no admiration. Philip’s gratitude would be to me, not to him. I begged, I threatened, we argued; and while we were arguing, Philip was arrested. It killed my mother—he was always her favourite—but Mark, as usual, got his satisfaction out of it. He preened himself on his judgment of character in having chosen me and not Philip twelve years before!

“Later on I apologized to Mark for the reckless things I had said to him, and he played the part of a magnanimous gentleman with his accustomed skill, but, though outwardly we were as before to each other, from that day forward, though his vanity would never let him see it, I was his bitterest enemy. If that had been all, I wonder if I should have killed him? To live on terms of intimate friendship with a man whom you hate is dangerous work for your friend. Because of his belief in me as his admiring and grateful protégé and his belief in himself as my benefactor, he was now utterly in my power. I could take my time and choose my opportunity. Perhaps I should not have killed him, but I had sworn to have my revenge—and there he was, poor vain fool, at my mercy. I was in no hurry.

“Two years later I had to reconsider my position, for my revenge was being taken out of my hands. Mark began to drink. Could I have stopped him? I don’t think so, but to my immense surprise I found myself trying to. Instinct, perhaps, getting the better of reason; or did I reason it out and tell myself that, if he drank himself to death, I should lose my revenge? Upon my word, I cannot tell you; but, for whatever motive, I did genuinely want to stop it. Drinking is such a beastly thing, anyhow.

“I could not stop him, but I kept him within certain bounds, so that nobody but myself knew his secret. Yes, I kept him outwardly decent; and perhaps now I was becoming like the cannibal who keeps his victim in good condition for his own ends. I used to gloat over Mark, thinking how utterly he was mine to ruin as I pleased, financially, morally, whatever way would give me most satisfaction. I had but to take my hand away from him and he sank. But again I was in no hurry.

“Then he killed himself. That futile little drunkard, eaten up with his own selfishness and vanity, offered his beastliness to the truest and purest woman on this earth. You have seen her, Mr. Gillingham, but you never knew Mark Ablett. Even if he had not been a drunkard, there was no chance for her of happiness with him. I had known him for many years, but never once had I seen him moved by any generous emotion. To have lived with that shrivelled little soul would have been hell for her; and a thousand times worse hell when he began to drink.

“So he had to be killed. I was the only one left to protect her, for her mother was in league with Mark to bring about her ruin. I would have shot him openly for her sake, and with what gladness, but I had no mind to sacrifice myself needlessly. He was in my power; I could persuade him to almost anything by flattery; surely it would not be difficult to give his death the appearance of an accident.

“I need not take up your time by telling you of the many plans I made and rejected. For some

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)