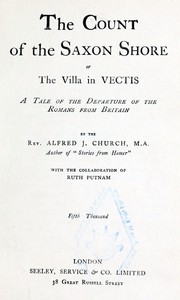

The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (electric book reader .TXT) 📖

- Author: Church and Putnam

Book online «The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (electric book reader .TXT) 📖». Author Church and Putnam

“Peace, dear mother,” said the centurion, soothingly, afraid that her words might have other listeners.

“Why not you,” went on the old woman, unheeding; “you are better born.”

“I, Emperor!” cried the centurion. “Speak good words, dearest mother.”

“Well,” said the old woman, dropping her voice again, “they are poor creatures now-a-days.” And she relapsed into silence, looking again as wholly indifferent to the present as if the strange outburst of rage and impatience which her family had just witnessed had never taken place.

The family discussed the position of affairs anxiously till far into the night.

“And what will happen,” said the wife, “when the legions are gone?”

“There will be a British kingdom, I suppose; and, if it were united, it might stand. But it [pg 93]will not be united. It will be every man for himself.”

“And how about the Saxons and the Picts? If the legions hardly protected us from them, how will it be when they are gone?”

The centurion’s look grew gloomier than ever. “I know,” he said, “the prospect is a sad one. But I hope that for a year you will be fairly safe; and after that I shall hope to send for you. Or you might go over to Gaul. But I hope to see the Count of the Shore about these matters. He will give me the best advice. Here, of course, you can hardly stay, even if you cared to do it; and some place must be found. Meanwhile, make all the preparations you can for a move.”

THE DEPARTURE OF THE LEGIONS.

The resolution to leave Britain was announced at a general meeting of the soldiers on the following day, and was received by it with tremendous enthusiasm. To most who were present, Gaul seemed a land of promise. It was from Gaul that almost every article of luxury that they either had or wished to have was imported, and some of the necessities of life, as notably wine, were known to be both better and cheaper there than in Britain. Comfortable quarters in wealthy cities, which were ready to be friendly, or could easily be brought to reason if they were not; easy campaigns, not against naked Picts, but against civilized enemies who had something to lose; and when the time of service was over, a snug little farm, with corn land, pasture, and vineyard, and a hard-working native to till it—such were the dreams which floated through the soldiers’ minds; and they were ready to go anywhere with the man [pg 95]who promised to make them into realities. Older and more prudent men who knew that there were two sides to the question, and the unadventurous, who were well content to stay where they were, could not resist the tide of popular feeling, and concealed, if they did not abandon, their doubts and scruples. As money was scarce, the men volunteered to forego their pay till it could be returned to them with large interest in the shape of prize-money. They even gave up to the melting pot the silver ornaments from their arms and from the trappings of their horses. The messengers who were sent with the tidings of the proposed movement to the other camps—which were now mainly to be found in the southern part of the island—found the troops everywhere well disposed, and within a few days every military station was alive with the stir and bustle of preparations for a move.

One of the most pressing cares of the new leaders of the army was the securing the means of transport. There was a great number of merchant ships, indeed, which could be pressed into the service, and which would perform it very well if only the passage in the Channel could be made without meeting opposition. The question to be considered was whether they could reckon upon this, or would the fleet, which was still supposed to acknowledge the authority of Honorius, prevent them from crossing. The chief person to be reckoned with in this matter was, of [pg 96]course, the Count of the Shore, and a despatch was immediately sent to him. It was the production of Constans, and ran thus—

“Constantine, Emperor of Britain and the West, to Lucius Ælius, Count of the Saxon Shore, greeting.

“Having been called to Empire by the unanimous voice of the People and Army of Britain, and desiring to give deliverance from tyranny and protection from violence to other provinces besides this my Island of Britain, I purpose to transport such forces as it may be necessary to use for this purpose to the land of Gaul. I call upon you therefore, having full confidence in your loyalty, to give me such assistance as may be in your power, for the accomplishment of this end, and promise you, on the other hand, my favour and protection. Farewell.

“Given at the Camp of the Great Harbour.”

The Count received this communication about ten days after his arrival at the villa. The writer would scarcely have been pleased at the comments which he made as he read it.

“ ‘Constantine, Emperor.’ How many more Emperors are we to have in this unlucky island? ‘Of Britain and the West.’ And I doubt whether he can call a foot of ground his own fifty miles from the

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)