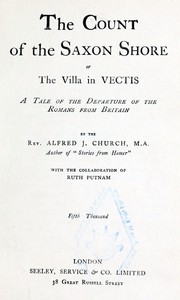

The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (electric book reader .TXT) 📖

- Author: Church and Putnam

Book online «The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (electric book reader .TXT) 📖». Author Church and Putnam

Slowly, as ship after ship received its complement of men, the turmoil on the shore lessened, and about sunset the embarkation was completed. The weather was beautifully calm, a light wind blowing from the land during the day, and even this falling as the [pg 106]light declined. When the moon rose—the time of the full had been chosen for the embarkation—the sea was almost calm. Then, amidst a great cry of “Farewell,” from the shore, the fleet slowly moved down the harbour. All night, making the most of the favourable weather, it pursued its way along the coast, being joined as it went by other detachments. At the Portus Lemanus it found the fleet which carried the garrisons of the eastern stations ready to start, and the whole made its way without hindrance across the Channel to Bononia, having as prosperous a voyage as had the legions which more than four hundred and fifty years before Cæsar had brought to the island.

DANGERS AHEAD.

The winter that followed the departure of the legions was a busy time with the Count. He was now almost the only representative of Roman power in Southern Britain, and the villa on the island became a place of considerable importance. A military force of some strength was gathered there. Constantine’s enterprise was not universally popular, and many had taken any chance that offered itself of escaping from it. Some had reached, or very nearly reached, the end of their time of service, and claimed their discharge; others were known to be loyal to Rome, and were allowed to retire. Not a few of those who found themselves without home or employment, and did not happen to have friends or kinsfolk in Britain, rallied to the Count. The families, too, of some that had gone with the legions were glad to claim such shelter and protection as the neighbourhood of the villa could give. Among these were the wife and [pg 108]daughters of the Centurion Decius; the old mother had steadily refused to accompany them, and, with an aged dependent of nearly the same age, continued to occupy the house near the deserted camp. It was an anxious matter with the Count what was to be done with these helpless people. While things were quiet they could live safely, if not very comfortably, in the neighbouring village; but if trouble were to come—and there were several quarters from which it might come—they would have to be sheltered somewhere in the villa. This never could be made into a really strong place; but it might serve well enough for a time and against ordinary attack. Some of the outbuildings and domestic offices were fortified as well as the position admitted; such material of war as could be got was accumulated, and provisions also were stored. The most reliable resource, however, was in the ships of war. These were not, as was usual, drawn up on the beach for the winter, but were kept at anchor, ready for immediate use.

Nor were these precautions unnecessary, for indeed, as we shall see, mischief of a very formidable kind was brewing, and indeed had been brewing ever since the departure of the legions, and even before that event. And it was mischief of a kind of which it may safely be affirmed that neither the Count nor any Roman official, had any notion. Britain, to [pg 109]all appearance, had for many generations been thoroughly subdued. Any Roman, if he had been told that there was any danger of rebellion among the Britons, would have laughed the suggestion to scorn. The legions, indeed, had often been mutinous and turbulent, and their generals ambitious and unscrupulous. The island indeed had gained so bad a reputation for loyalty to the Empire that it had been called the mother of tyrants, by “tyrant” being meant “usurper.” But whenever Rome had been defied, she had been defied by her own troops. The Britons had enlisted in the rebel armies, but they had never attempted to assert anything like British independence. And yet the tradition of independence and liberty had always been kept alive. The Celtic race is singularly tenacious of such ideas, and also singularly skilful in concealing them from those who are its masters for the time, and the Britons were Celts of the purest blood. Caradoc33 and Boadicea, and other heroes and heroines of British independence, were household words in many families which were yet thoroughly Roman in spirit and manners. Just as the Christianized Jews of Spain, though to all appearances devout worshippers at church, still clung in secret to the rites of their own worship, so these loyal subjects of the Empire, as all the world [pg 110]believed them, cherished in their hearts the memory of the free Britain of the past and the hope of a free Britain in the future. And the time was now at hand when their leaders thought that this hope might be fulfilled.

The Shanklin Chine of to-day is not a little different from the Shanklin Chine of fifteen hundred years ago. It has, so to speak, been subdued and civilized. Now it is a very pretty and pleasant wood; then it was an almost impenetrable thicket, a noted lair of elk and wild boar. Inaccessible, however, as it seemed to any one who surveyed it from above, there was for those who were in the secret a way of approaching its recesses. A little path, the beginning of which it was almost impossible to discover without a guide, led up from the sea-end of the

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)