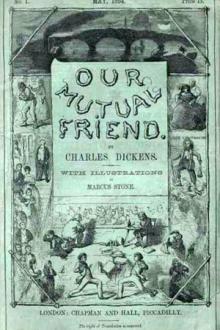

Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Book online «Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖». Author Charles Dickens

'That, sir,' replied Mr Wegg, cheering up bravely, 'is quite another pair of shoes. Now, my independence as a man is again elevated. Now, I no longer

When to Boffinses bower,

The Lord of the valley with offers came;

Neither does the moon hide her light

From the heavens to-night,

And weep behind her clouds o'er any individual in the present

Company's shame.

—Please to proceed, Mr Boffin.'

'Thank'ee, Wegg, both for your confidence in me and for your frequent dropping into poetry; both of which is friendly. Well, then; my idea is, that you should give up your stall, and that I should put you into the Bower here, to keep it for us. It's a pleasant spot; and a man with coals and candles and a pound a week might be in clover here.'

'Hem! Would that man, sir—we will say that man, for the purposes of argueyment;' Mr Wegg made a smiling demonstration of great perspicuity here; 'would that man, sir, be expected to throw any other capacity in, or would any other capacity be considered extra? Now let us (for the purposes of argueyment) suppose that man to be engaged as a reader: say (for the purposes of argueyment) in the evening. Would that man's pay as a reader in the evening, be added to the other amount, which, adopting your language, we will call clover; or would it merge into that amount, or clover?'

'Well,' said Mr Boffin, 'I suppose it would be added.'

'I suppose it would, sir. You are right, sir. Exactly my own views, Mr Boffin.' Here Wegg rose, and balancing himself on his wooden leg, fluttered over his prey with extended hand. 'Mr Boffin, consider it done. Say no more, sir, not a word more. My stall and I are for ever parted. The collection of ballads will in future be reserved for private study, with the object of making poetry tributary'—Wegg was so proud of having found this word, that he said it again, with a capital letter—'Tributary, to friendship. Mr Boffin, don't allow yourself to be made uncomfortable by the pang it gives me to part from my stock and stall. Similar emotion was undergone by my own father when promoted for his merits from his occupation as a waterman to a situation under Government. His Christian name was Thomas. His words at the time (I was then an infant, but so deep was their impression on me, that I committed them to memory) were:

Oars and coat and badge farewell!

Never more at Chelsea Ferry,

Shall your Thomas take a spell!

—My father got over it, Mr Boffin, and so shall I.'

While delivering these valedictory observations, Wegg continually disappointed Mr Boffin of his hand by flourishing it in the air. He now darted it at his patron, who took it, and felt his mind relieved of a great weight: observing that as they had arranged their joint affairs so satisfactorily, he would now be glad to look into those of Bully Sawyers. Which, indeed, had been left over-night in a very unpromising posture, and for whose impending expedition against the Persians the weather had been by no means favourable all day.

Mr Wegg resumed his spectacles therefore. But Sawyers was not to be of the party that night; for, before Wegg had found his place, Mrs Boffin's tread was heard upon the stairs, so unusually heavy and hurried, that Mr Boffin would have started up at the sound, anticipating some occurrence much out of the common course, even though she had not also called to him in an agitated tone.

Mr Boffin hurried out, and found her on the dark staircase, panting, with a lighted candle in her hand.

'What's the matter, my dear?'

'I don't know; I don't know; but I wish you'd come up-stairs.'

Much surprised, Mr Boffin went up stairs and accompanied Mrs Boffin into their own room: a second large room on the same floor as the room in which the late proprietor had died. Mr Boffin looked all round him, and saw nothing more unusual than various articles of folded linen on a large chest, which Mrs Boffin had been sorting.

'What is it, my dear? Why, you're frightened! You frightened?'

'I am not one of that sort certainly,' said Mrs Boffin, as she sat down in a chair to recover herself, and took her husband's arm; 'but it's very strange!'

'What is, my dear?'

'Noddy, the faces of the old man and the two children are all over the house to-night.'

'My dear?' exclaimed Mr Boffin. But not without a certain uncomfortable sensation gliding down his back.

'I know it must sound foolish, and yet it is so.'

'Where did you think you saw them?'

'I don't know that I think I saw them anywhere. I felt them.'

'Touched them?'

'No. Felt them in the air. I was sorting those things on the chest, and not thinking of the old man or the children, but singing to myself, when all in a moment I felt there was a face growing out of the dark.'

'What face?' asked her husband, looking about him.

'For a moment it was the old man's, and then it got younger. For a moment it was both the children's, and then it got older. For a moment it was a strange face, and then it was all the faces.'

'And then it was gone?'

'Yes; and then it was gone.'

'Where were you then, old lady?'

'Here, at the chest. Well; I got the better of it, and went on sorting, and went on singing to myself. “Lor!” I says, “I'll think of something else—something comfortable—and put it out of my head.” So I thought of the new house and Miss Bella Wilfer, and was thinking at a great rate with that sheet there in my hand, when all of a sudden, the faces seemed to be hidden in among the folds of it and I let it drop.'

As it still lay on the floor where it had fallen, Mr Boffin picked it up and laid it on the chest.

'And then you ran down stairs?'

'No. I thought I'd try another room, and shake it off. I says to myself, “I'll go and walk slowly up and down the old man's room three times, from end to end, and then I shall have conquered it.” I went in with the candle in my hand; but the moment I came near the bed, the air got thick with them.'

'With the faces?'

'Yes, and I even felt that they were in the dark behind the side-door, and on the little staircase, floating away into the yard. Then, I called you.'

Mr Boffin, lost in amazement, looked at Mrs Boffin. Mrs Boffin, lost in her own fluttered inability to make this out, looked at Mr Boffin.

'I think, my dear,' said the Golden Dustman, 'I'll at once get rid of Wegg for the night, because he's coming to inhabit the Bower, and it might be put into his head or somebody else's, if he heard this and it got about that the house is haunted. Whereas we know better. Don't we?'

'I never had the feeling in the house before,' said Mrs Boffin; 'and I have been about it alone at all hours of the night. I have been in the house when Death was in it, and I have been in the house when Murder was a new part of its adventures, and I never had a fright in it yet.'

'And won't again, my dear,' said Mr Boffin. 'Depend upon it, it comes of thinking and dwelling on that dark spot.'

'Yes; but why didn't it come before?' asked Mrs Boffin.

This draft on Mr Boffin's philosophy could only be met by that gentleman with the remark that everything that is at all, must begin at some time. Then, tucking his wife's arm under his own, that she might not be left by herself to be troubled again, he descended to release Wegg. Who, being something drowsy after his plentiful repast, and constitutionally of a shirking temperament, was well enough pleased to stump away, without doing what he had come to do, and was paid for doing.

Mr Boffin then put on his hat, and Mrs Boffin her shawl; and the pair, further provided with a bunch of keys and a lighted lantern, went all over the dismal house—dismal everywhere, but in their own two rooms—from cellar to cock-loft. Not resting satisfied with giving that much chace to Mrs Boffin's fancies, they pursued them into the yard and outbuildings, and under the Mounds. And setting the lantern, when all was done, at the foot of one of the Mounds, they comfortably trotted to and fro for an evening walk, to the end that the murky cobwebs in Mrs Boffin's brain might be blown away.

'There, my dear!' said Mr Boffin when they came in to supper. 'That was the treatment, you see. Completely worked round, haven't you?'

'Yes, deary,' said Mrs Boffin, laying aside her shawl. 'I'm not nervous any more. I'm not a bit troubled now. I'd go anywhere about the house the same as ever. But—'

'Eh!' said Mr Boffin.

'But I've only to shut my eyes.'

'And what then?'

'Why then,' said Mrs Boffin, speaking with her eyes closed, and her left hand thoughtfully touching her brow, 'then, there they are! The old man's face, and it gets younger. The two children's faces, and they get older. A face that I don't know. And then all the faces!'

Opening her eyes again, and seeing her husband's face across the table, she leaned forward to give it a pat on the cheek, and sat down to supper, declaring it to be the best face in the world.

Chapter 16 MINDERS AND RE-MINDERS

The Secretary lost no time in getting to work, and his vigilance and method soon set their mark on the Golden Dustman's affairs. His earnestness in determining to understand the length and breadth and depth of every piece of work submitted to him by his employer, was as special as his despatch in transacting it. He accepted no information or explanation at second hand, but made himself the master of everything confided to him.

One part of the Secretary's conduct, underlying all the rest, might have been mistrusted by a man with a better knowledge of men than the Golden Dustman had. The Secretary was as far from being inquisitive or intrusive as Secretary could be, but nothing less than a complete understanding of the whole of the affairs would content him. It soon became apparent (from the knowledge with which he set out) that he must have been to the office where the Harmon will was registered, and must have read the will. He anticipated Mr Boffin's consideration whether he should be advised with on this or that topic, by showing that he already knew of it and understood it. He did this with no attempt at concealment, seeming to be satisfied that it was part of his duty to have prepared himself at all attainable points for its utmost discharge.

This might—let it be repeated—have awakened some little vague mistrust in a man more worldly-wise than the Golden Dustman. On the other hand, the Secretary was discerning, discreet, and silent, though as zealous as if the affairs had been his own. He showed no love of patronage or the command of money, but distinctly preferred resigning both to Mr Boffin. If, in his limited sphere, he sought power, it was the power of knowledge; the power derivable from a perfect comprehension of his business.

As on the Secretary's face there was a nameless cloud, so on his manner there was a shadow equally indefinable. It was not that he was embarrassed, as on that first night with the Wilfer family; he was habitually unembarrassed now, and yet the something remained. It was not that his manner was bad, as on that occasion; it was now very good, as being modest, gracious, and ready.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)