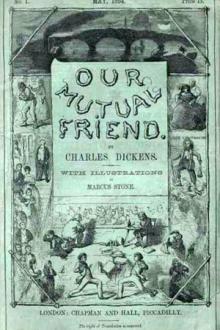

Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Book online «Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖». Author Charles Dickens

Mrs Betty Higden's visitor pressed her hand. There was no more breaking up of the strong old face into weakness. My Lords and Gentlemen and Honourable Boards, it really was as composed as our own faces, and almost as dignified.

And now, Johnny was to be inveigled into occupying a temporary position on Mrs Boffin's lap. It was not until he had been piqued into competition with the two diminutive Minders, by seeing them successively raised to that post and retire from it without injury, that he could be by any means induced to leave Mrs Betty Higden's skirts; towards which he exhibited, even when in Mrs Boffin's embrace, strong yearnings, spiritual and bodily; the former expressed in a very gloomy visage, the latter in extended arms. However, a general description of the toy-wonders lurking in Mr Boffin's house, so far conciliated this worldly-minded orphan as to induce him to stare at her frowningly, with a fist in his mouth, and even at length to chuckle when a richly-caparisoned horse on wheels, with a miraculous gift of cantering to cake-shops, was mentioned. This sound being taken up by the Minders, swelled into a rapturous trio which gave general satisfaction.

So, the interview was considered very successful, and Mrs Boffin was pleased, and all were satisfied. Not least of all, Sloppy, who undertook to conduct the visitors back by the best way to the Three Magpies, and whom the hammer-headed young man much despised.

This piece of business thus put in train, the Secretary drove Mrs Boffin back to the Bower, and found employment for himself at the new house until evening. Whether, when evening came, he took a way to his lodgings that led through fields, with any design of finding Miss Bella Wilfer in those fields, is not so certain as that she regularly walked there at that hour.

And, moreover, it is certain that there she was.

No longer in mourning, Miss Bella was dressed in as pretty colours as she could muster. There is no denying that she was as pretty as they, and that she and the colours went very prettily together. She was reading as she walked, and of course it is to be inferred, from her showing no knowledge of Mr Rokesmith's approach, that she did not know he was approaching.

'Eh?' said Miss Bella, raising her eyes from her book, when he stopped before her. 'Oh! It's you.'

'Only I. A fine evening!'

'Is it?' said Bella, looking coldly round. 'I suppose it is, now you mention it. I have not been thinking of the evening.'

'So intent upon your book?'

'Ye-e-es,' replied Bella, with a drawl of indifference.

'A love story, Miss Wilfer?'

'Oh dear no, or I shouldn't be reading it. It's more about money than anything else.'

'And does it say that money is better than anything?'

'Upon my word,' returned Bella, 'I forget what it says, but you can find out for yourself if you like, Mr Rokesmith. I don't want it any more.'

The Secretary took the book—she had fluttered the leaves as if it were a fan—and walked beside her.

'I am charged with a message for you, Miss Wilfer.'

'Impossible, I think!' said Bella, with another drawl.

'From Mrs Boffin. She desired me to assure you of the pleasure she has in finding that she will be ready to receive you in another week or two at furthest.'

Bella turned her head towards him, with her prettily-insolent eyebrows raised, and her eyelids drooping. As much as to say, 'How did you come by the message, pray?'

'I have been waiting for an opportunity of telling you that I am Mr Boffin's Secretary.'

'I am as wise as ever,' said Miss Bella, loftily, 'for I don't know what a Secretary is. Not that it signifies.'

'Not at all.'

A covert glance at her face, as he walked beside her, showed him that she had not expected his ready assent to that proposition.

'Then are you going to be always there, Mr Rokesmith?' she inquired, as if that would be a drawback.

'Always? No. Very much there? Yes.'

'Dear me!' drawled Bella, in a tone of mortification.

'But my position there as Secretary, will be very different from yours as guest. You will know little or nothing about me. I shall transact the business: you will transact the pleasure. I shall have my salary to earn; you will have nothing to do but to enjoy and attract.'

'Attract, sir?' said Bella, again with her eyebrows raised, and her eyelids drooping. 'I don't understand you.'

Without replying on this point, Mr Rokesmith went on.

'Excuse me; when I first saw you in your black dress—'

('There!' was Miss Bella's mental exclamation. 'What did I say to them at home? Everybody noticed that ridiculous mourning.')

'When I first saw you in your black dress, I was at a loss to account for that distinction between yourself and your family. I hope it was not impertinent to speculate upon it?'

'I hope not, I am sure,' said Miss Bella, haughtily. 'But you ought to know best how you speculated upon it.'

Mr Rokesmith inclined his head in a deprecatory manner, and went on.

'Since I have been entrusted with Mr Boffin's affairs, I have necessarily come to understand the little mystery. I venture to remark that I feel persuaded that much of your loss may be repaired. I speak, of course, merely of wealth, Miss Wilfer. The loss of a perfect stranger, whose worth, or worthlessness, I cannot estimate—nor you either—is beside the question. But this excellent gentleman and lady are so full of simplicity, so full of generosity, so inclined towards you, and so desirous to—how shall I express it?—to make amends for their good fortune, that you have only to respond.'

As he watched her with another covert look, he saw a certain ambitious triumph in her face which no assumed coldness could conceal.

'As we have been brought under one roof by an accidental combination of circumstances, which oddly extends itself to the new relations before us, I have taken the liberty of saying these few words. You don't consider them intrusive I hope?' said the Secretary with deference.

'Really, Mr Rokesmith, I can't say what I consider them,' returned the young lady. 'They are perfectly new to me, and may be founded altogether on your own imagination.'

'You will see.'

These same fields were opposite the Wilfer premises. The discreet Mrs Wilfer now looking out of window and beholding her daughter in conference with her lodger, instantly tied up her head and came out for a casual walk.

'I have been telling Miss Wilfer,' said John Rokesmith, as the majestic lady came stalking up, 'that I have become, by a curious chance, Mr Boffin's Secretary or man of business.'

'I have not,' returned Mrs Wilfer, waving her gloves in her chronic state of dignity, and vague ill-usage, 'the honour of any intimate acquaintance with Mr Boffin, and it is not for me to congratulate that gentleman on the acquisition he has made.'

'A poor one enough,' said Rokesmith.

'Pardon me,' returned Mrs Wilfer, 'the merits of Mr Boffin may be highly distinguished—may be more distinguished than the countenance of Mrs Boffin would imply—but it were the insanity of humility to deem him worthy of a better assistant.'

'You are very good. I have also been telling Miss Wilfer that she is expected very shortly at the new residence in town.'

'Having tacitly consented,' said Mrs Wilfer, with a grand shrug of her shoulders, and another wave of her gloves, 'to my child's acceptance of the proffered attentions of Mrs Boffin, I interpose no objection.'

Here Miss Bella offered the remonstrance: 'Don't talk nonsense, ma, please.'

'Peace!' said Mrs Wilfer.

'No, ma, I am not going to be made so absurd. Interposing objections!'

'I say,' repeated Mrs Wilfer, with a vast access of grandeur, 'that I am not going to interpose objections. If Mrs Boffin (to whose countenance no disciple of Lavater could possibly for a single moment subscribe),' with a shiver, 'seeks to illuminate her new residence in town with the attractions of a child of mine, I am content that she should be favoured by the company of a child of mine.'

'You use the word, ma'am, I have myself used,' said Rokesmith, with a glance at Bella, 'when you speak of Miss Wilfer's attractions there.'

'Pardon me,' returned Mrs Wilfer, with dreadful solemnity, 'but I had not finished.'

'Pray excuse me.'

'I was about to say,' pursued Mrs Wilfer, who clearly had not had the faintest idea of saying anything more: 'that when I use the term attractions, I do so with the qualification that I do not mean it in any way whatever.'

The excellent lady delivered this luminous elucidation of her views with an air of greatly obliging her hearers, and greatly distinguishing herself. Whereat Miss Bella laughed a scornful little laugh and said:

'Quite enough about this, I am sure, on all sides. Have the goodness, Mr Rokesmith, to give my love to Mrs Boffin—'

'Pardon me!' cried Mrs Wilfer. 'Compliments.'

'Love!' repeated Bella, with a little stamp of her foot.

'No!' said Mrs Wilfer, monotonously. 'Compliments.'

('Say Miss Wilfer's love, and Mrs Wilfer's compliments,' the Secretary proposed, as a compromise.)

'And I shall be very glad to come when she is ready for me. The sooner, the better.'

'One last word, Bella,' said Mrs Wilfer, 'before descending to the family apartment. I trust that as a child of mine you will ever be sensible that it will be graceful in you, when associating with Mr and Mrs Boffin upon equal terms, to remember that the Secretary, Mr Rokesmith, as your father's lodger, has a claim on your good word.'

The condescension with which Mrs Wilfer delivered this proclamation of patronage, was as wonderful as the swiftness with which the lodger had lost caste in the Secretary. He smiled as the mother retired down stairs; but his face fell, as the daughter followed.

'So insolent, so trivial, so capricious, so mercenary, so careless, so hard to touch, so hard to turn!' he said, bitterly.

And added as he went upstairs. 'And yet so pretty, so pretty!'

And added presently, as he walked to and fro in his room. 'And if she knew!'

She knew that he was shaking the house by his walking to and fro; and she declared it another of the miseries of being poor, that you couldn't get rid of a haunting Secretary, stump—stump—stumping overhead in the dark, like a Ghost.

Chapter 17 A DISMAL SWAMP

And now, in the blooming summer days, behold Mr and Mrs Boffin established in the eminently aristocratic family mansion, and behold all manner of crawling, creeping, fluttering, and buzzing creatures, attracted by the gold dust of the Golden Dustman!

Foremost among those leaving cards at the eminently aristocratic door before it is quite painted, are the Veneerings: out of breath, one might imagine, from the impetuosity of their rush to the eminently aristocratic steps. One copper-plate Mrs Veneering, two copper-plate Mr Veneerings, and a connubial copper-plate Mr and Mrs Veneering, requesting the honour of Mr and Mrs Boffin's company at dinner with the utmost Analytical solemnities. The enchanting Lady Tippins leaves a card. Twemlow leaves cards. A tall custard-coloured phaeton tooling up in a solemn manner leaves four cards, to wit, a couple of Mr Podsnaps, a Mrs Podsnap, and

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)