Mike by Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (dar e dil novel online reading .TXT) 📖

- Author: Pelham Grenville Wodehouse

- Performer: -

Book online «Mike by Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (dar e dil novel online reading .TXT) 📖». Author Pelham Grenville Wodehouse

extent. But, at any rate at first, it was no time for science. To be

scientific one must have an opponent who observes at least the more

important rules of the ring. It is impossible to do the latest ducks

and hooks taught you by the instructor if your antagonist butts you in

the chest, and then kicks your shins, while some dear friend of his,

of whose presence you had no idea, hits you at the same time on the

back of the head. The greatest expert would lose his science in such

circumstances.

Probably what gave the school the victory in the end was the

righteousness of their cause. They were smarting under a sense of

injury, and there is nothing that adds a force to one’s blows and a

recklessness to one’s style of delivering them more than a sense of

injury.

Wyatt, one side of his face still showing traces of the tomato, led

the school with a vigour that could not be resisted. He very seldom

lost his temper, but he did draw the line at bad tomatoes.

Presently the school noticed that the enemy were vanishing little by

little into the darkness which concealed the town. Barely a dozen

remained. And their lonely condition seemed to be borne in upon these

by a simultaneous brain-wave, for they suddenly gave the fight up, and

stampeded as one man.

The leaders were beyond recall, but two remained, tackled low by Wyatt

and Clowes after the fashion of the football-field.

*

The school gathered round its prisoners, panting. The scene of the

conflict had shifted little by little to a spot some fifty yards from

where it had started. By the side of the road at this point was a

green, depressed looking pond. Gloomy in the daytime, it looked

unspeakable at night. It struck Wyatt, whose finer feelings had been

entirely blotted out by tomato, as an ideal place in which to bestow

the captives.

“Let’s chuck ‘em in there,” he said.

The idea was welcomed gladly by all, except the prisoners. A move was

made towards the pond, and the procession had halted on the brink,

when a new voice made itself heard.

“Now then,” it said, “what’s all this?”

A stout figure in policeman’s uniform was standing surveying them with

the aid of a small bull’s-eye lantern.

“What’s all this?”

“It’s all right,” said Wyatt.

“All right, is it? What’s on?”

One of the prisoners spoke.

“Make ‘em leave hold of us, Mr. Butt. They’re a-going to chuck us in

the pond.”

“Ho!” said the policeman, with a change in his voice. “Ho, are they?

Come now, young gentleman, a lark’s a lark, but you ought to know

where to stop.”

“It’s anything but a lark,” said Wyatt in the creamy voice he used

when feeling particularly savage. “We’re the Strong Right Arm of

Justice. That’s what we are. This isn’t a lark, it’s an execution.”

“I don’t want none of your lip, whoever you are,” said Mr. Butt,

understanding but dimly, and suspecting impudence by instinct.

“This is quite a private matter,” said Wyatt. “You run along on your

beat. You can’t do anything here.”

“Ho!”

“Shove ‘em in, you chaps.”

“Stop!” From Mr. Butt.

“Oo-er!” From prisoner number one.

There was a sounding splash as willing hands urged the first of the

captives into the depths. He ploughed his way to the bank, scrambled

out, and vanished.

Wyatt turned to the other prisoner.

“You’ll have the worst of it, going in second. He’ll have churned up

the mud a bit. Don’t swallow more than you can help, or you’ll go

getting typhoid. I expect there are leeches and things there, but if

you nip out quick they may not get on to you. Carry on, you chaps.”

It was here that the regrettable incident occurred. Just as the second

prisoner was being launched, Constable Butt, determined to assert

himself even at the eleventh hour, sprang forward, and seized the

captive by the arm. A drowning man will clutch at a straw. A man about

to be hurled into an excessively dirty pond will clutch at a stout

policeman. The prisoner did.

Constable Butt represented his one link with dry land. As he came

within reach he attached himself to his tunic with the vigour and

concentration of a limpet.

At the same moment the executioners gave their man the final heave.

The policeman realised his peril too late. A medley of noises made the

peaceful night hideous. A howl from the townee, a yell from the

policeman, a cheer from the launching party, a frightened squawk from

some birds in a neighbouring tree, and a splash compared with which

the first had been as nothing, and all was over.

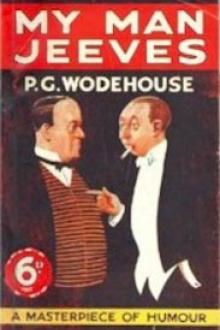

The dark waters were lashed into a maelstrom; and then two streaming

figures squelched up the further bank.

[Illustration: THE DARK WATERS WERE LASHED INTO A MAELSTROM]

The school stood in silent consternation. It was no occasion for light

apologies.

“Do you know,” said Wyatt, as he watched the Law shaking the water

from itself on the other side of the pond, “I’m not half sure that we

hadn’t better be moving!”

BEFORE THE STORM

Your real, devastating row has many points of resemblance with a

prairie fire. A man on a prairie lights his pipe, and throws away the

match. The flame catches a bunch of dry grass, and, before any one can

realise what is happening, sheets of fire are racing over the country;

and the interested neighbours are following their example. (I have

already compared a row with a thunderstorm; but both comparisons may

stand. In dealing with so vast a matter as a row there must be no

stint.)

The tomato which hit Wyatt in the face was the thrown-away match. But

for the unerring aim of the town marksman great events would never

have happened. A tomato is a trivial thing (though it is possible that

the man whom it hits may not think so), but in the present case, it

was the direct cause of epoch-making trouble.

The tomato hit Wyatt. Wyatt, with others, went to look for the

thrower. The remnants of the thrower’s friends were placed in the

pond, and “with them,” as they say in the courts of law, Police

Constable Alfred Butt.

Following the chain of events, we find Mr. Butt, having prudently

changed his clothes, calling upon the headmaster.

The headmaster was grave and sympathetic; Mr. Butt fierce and

revengeful.

The imagination of the force is proverbial. Nurtured on motorcars and

fed with stop-watches, it has become world-famous. Mr. Butt gave free

rein to it.

“Threw me in, they did, sir. Yes, sir.”

“Threw you in!”

“Yes, sir. Plop!” said Mr. Butt, with a certain sad relish.

“Really, really!” said the headmaster. “Indeed! This is—dear me! I

shall certainly—They threw you in!—Yes, I shall—certainly–-”

Encouraged by this appreciative reception of his story, Mr. Butt

started it again, right from the beginning.

“I was on my beat, sir, and I thought I heard a disturbance. I says to

myself, ”Allo,’ I says, ‘a frakkus. Lots of them all gathered

together, and fighting.’ I says, beginning to suspect something,

‘Wot’s this all about, I wonder?’ I says. ‘Blow me if I don’t think

it’s a frakkus.’ And,” concluded Mr. Butt, with the air of one

confiding a secret, “and it was a frakkus!”

“And these boys actually threw you into the pond?”

“Plop, sir! Mrs. Butt is drying my uniform at home at this very

moment as we sit talking here, sir. She says to me, ‘Why, whatever

‘ave you been a-doing? You’re all wet.’ And,” he added, again

with the confidential air, “I was wet, too. Wringin’ wet.”

The headmaster’s frown deepened.

“And you are certain that your assailants were boys from the school?”

“Sure as I am that I’m sitting here, sir. They all ‘ad their caps on

their heads, sir.”

“I have never heard of such a thing. I can hardly believe that it is

possible. They actually seized you, and threw you into the water–-”

“Splish, sir!” said the policeman, with a vividness of imagery

both surprising and gratifying.

The headmaster tapped restlessly on the floor with his foot.

“How many boys were there?” he asked.

“Couple of ‘undred, sir,” said Mr. Butt promptly.

“Two hundred!”

“It was dark, sir, and I couldn’t see not to say properly; but if you

ask me my frank and private opinion I should say couple of ‘undred.”

“H’m—Well, I will look into the matter at once. They shall be

punished.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ye-e-s—H’m—Yes—Most severely.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Yes—Thank you, constable. Good-night.”

“Good-night, sir.”

The headmaster of Wrykyn was not a motorist. Owing to this

disadvantage he made a mistake. Had he been a motorist, he would have

known that statements by the police in the matter of figures must be

divided by any number from two to ten, according to discretion. As it

was, he accepted Constable Butt’s report almost as it stood. He

thought that he might possibly have been mistaken as to the exact

numbers of those concerned in his immersion; but he accepted the

statement in so far as it indicated that the thing had been the work

of a considerable section of the school, and not of only one or two

individuals. And this made all the difference to his method of dealing

with the affair. Had he known how few were the numbers of those

responsible for the cold in the head which subsequently attacked

Constable Butt, he would have asked for their names, and an extra

lesson would have settled the entire matter.

As it was, however, he got the impression that the school, as a whole,

was culpable, and he proceeded to punish the school as a whole.

It happened that, about a week before the pond episode, a certain

member of the Royal Family had recovered from a dangerous illness,

which at one time had looked like being fatal. No official holiday had

been given to the schools in honour of the recovery, but Eton and

Harrow had set the example, which was followed throughout the kingdom,

and Wrykyn had come into line with the rest. Only two days before the

O.W.‘s matches the headmaster had given out a notice in the hall that

the following Friday would be a whole holiday; and the school, always

ready to stop work, had approved of the announcement exceedingly.

The step which the headmaster decided to take by way of avenging Mr.

Butt’s wrongs was to stop this holiday.

He gave out a notice to that effect on the Monday.

The school was thunderstruck. It could not understand it. The pond

affair had, of course, become public property; and those who had had

nothing to do with it had been much amused. “There’ll be a frightful

row about it,” they had said, thrilled with the pleasant excitement of

those who see trouble approaching and themselves looking on from a

comfortable distance without risk or uneasiness. They were not

malicious. They did not want to see their friends in difficulties. But

there is no denying that a row does break the monotony of a school

term. The thrilling feeling that something is going to happen is the

salt of life….

And here they were, right in it after all. The blow had fallen, and

crushed guilty and innocent alike.

Comments (0)