All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖». Author William H. Ukers

They have in Turkey a drink called coffa made of a berry of the same name, as black as soot, and of a strong scent, but not aromatical; which they take, beaten into powder, in water, as hot as they can drink it: and they take it, and sit at it in their coffa-houses, which are like our taverns. This drink comforteth the brain and heart, and helpeth digestion. Certainly this berry coffa, the root and leaf betel, the leaf tobacco, and the tear of poppy (opium) of which the Turks are great takers (supposing it expelleth all fear), do all condense the spirits, and make them strong and aleger. But it seemeth they were taken after several manners; for coffa and opium are taken down, tobacco but in smoke, and betel is but champed in the mouth with a little lime.

Robert Burton (1577–1640), English philosopher and humorist, in his Anatomy of Melancholy[54] writes in 1632:

The Turkes have a drinke called coffa (for they use no wine), so named of a berry as blacke as soot and as bitter (like that blacke drinke which was in use amongst the Lacedemonians and perhaps the same), which they sip still of, and sup as warme as they can suffer; they spend much time in those coffa-houses, which are somewhat like our Ale-houses or Taverns, and there they sit, chatting and drinking, to drive away the time, and to be merry together, because they find, by experience, that kinde of drinke so used, helpeth digestion and procureth alacrity.

Later English scholars, however, found sufficient evidence in the works of Arabian authors to assure their readers that coffee sometimes breeds melancholy, causes headache, and "maketh lean much." One of these, Dr. Pocoke, (1659: see chapter III) stated that, "he that would drink it for livelinesse sake, and to discusse slothfulnesse ... let him use much sweet meates with it, and oyle of pistaccioes, and butter. Some drink it with milk, but it is an error, and such as may bring in danger of the leprosy." Another writer observed that any ill effects caused by coffee, unlike those of tea, etc., ceased when its use was discontinued. In this connection it is interesting to note that in 1785 Dr. Benjamin Mosely, physician to the Chelsea Hospital, member of the College of Physicians, etc., probably having in mind the popular idea that the Arabic original of the word coffee meant force, or vigor, once expressed the hope that the coffee drink might return to popular favor in England as "a cheap substitute for those enervating teas and beverages which produce the pernicious habit of dram-drinking."

About 1628, Sir Thomas Herbert (1606–1681), English traveler and writer, records among his observations on the Persians that:

"They drink above all the rest Coho or Copha: by Turk and Arab called Caphe and Cahua: a drink imitating that in the Stigian lake, black, thick, and bitter: destrain'd from Bunchy, Bunnu, or Bay berries; wholesome, they say, if hot, for it expels melancholy ... but not so much regarded for those good properties, as from a Romance that it was invented and brew'd by Gabriel ... to restore the decayed radical Moysture of kind hearted Mahomet.'[55]

In 1634, Sir Henry Blount (1602–82), sometimes referred to as "the father of the English coffee house," made a journey on a Venetian galley into the Levant. He was invited to drink cauphe in the presence of Amurath IV; and later, in Egypt, he tells of being served the beverage again "in a porcelaine dish". This is how he describes the drink in Turkey:[56]

They have another drink not good at meat, called Cauphe, made of a Berry as big as a small Bean, dried in a Furnace, and beat to Pouder, of a Soot-colour, in taste a little bitterish, that they seeth and drink as hot as may be endured: It is good all hours of the day, but especially morning and evening, when to that purpose, they entertain themselves two or three hours in Cauphe-houses, which in all Turkey abound more than Inns and Ale-houses with us; it is thought to be the old black broth used so much by the Lacedemonians, and dryeth ill Humours in the stomach, comforteth the Brain, never causeth Drunkenness or any other Surfeit, and is a harmless entertainment of good Fellowship; for there upon Scaffolds half a yard high, and covered with Mats, they sit Cross-leg'd after the Turkish manner, many times two or three hundred together, talking, and likely with some poor musick passing up and down.

Photographed from the black-letter original of W. Parry's book in the Worth Library of the British Museum

This reference to the Lacedæmonian black broth, first by Sandys, then by Burton, again by Blount, and concurred in by James Howell (1595–1666), the first historiographer royal, gave rise to considerable controversy among Englishmen of letters in later years. It is, of course, a gratuitous speculation. The black broth of the Lacedæmonians was "pork, cooked in blood and seasoned with salt and vinegar.[57]"

From the black-letter original in the British Museum

William Harvey (1578–1657), the famous English physician who discovered the circulation of the blood, and his brother are reputed to have used coffee before coffee houses came into vogue in London—this must have been previous to 1652. "I remember", says Aubrey[58], "he was wont to drinke coffee; which his brother Eliab did, before coffee houses were the fashion in London." Houghton, in 1701, speaks of "the famous inventor of the circulation of the blood, Dr. Harvey, who some say did frequently use it."

Although it seems likely that coffee must have been introduced into England sometime during the first quarter of the seventeenth century, with so many writers and travelers describing it, and with so much trading going on between the merchants of the British Isles and the Orient, yet the first reliable record we have of its advent is to be found in the Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S.[59], under "Notes of 1637", where he says:

There came in my time to the college (Baliol, Oxford) one Nathaniel Conopios, out of Greece, from Cyrill, the Patriarch of Constantinople, who, returning many years after was made (as I understand) Bishop of Smyrna. He was the first I ever saw drink coffee; which custom came not into England till thirty years thereafter.

Evelyn should have said thirteen years after; for then it was that the first coffee house was opened (1650).

Conopios was a native of Crete, trained in the Greek church. He became primore to Cyrill, Patriarch of Constantinople. When Cyrill was strangled by the vizier, Conopios fled to England to avoid a like barbarity. He came with credentials to Archbishop Laud, who allowed him maintenance in Balliol College.

It was observed that while he continued in Balliol College he made the drink for his own use called Coffey, and usually drank it every morning, being the first, as the antients of that House have informed me, that was ever drank in Oxon.[60]

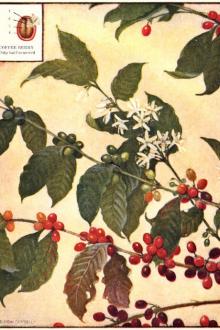

In 1640 John Parkinson (1567–1650), English botanist and herbalist, published his Theatrum Botanicum[61], containing the first botanical description of the coffee plant in English, referred to as "Arbor Bon cum sua Buna. The Turkes Berry Drinke".

His work being somewhat rare, it may be of historical interest to quote the quaint description here:

Alpinus, in his Booke of Egiptian plants, giveth us a description of this tree, which as hee saith, hee saw in the garden of a certain Captaine of the Ianissaries, which was brought out of Arabia felix and there planted as a rarity, never seene growing in those places before.

The tree, saith Alpinus, is somewhat like unto the Evonymus Pricketimber tree, whose leaves were thicker, harder, and greener, and always abiding greene on the tree; the fruite is called Buna and is somewhat bigger then an Hazell Nut and longer, round also, and pointed at the end, furrowed also on both sides, yet on one side more conspicuous than the other, that it might be parted in two, in each side whereof lyeth a small long white kernell, flat on that side they joyne together, covered with a yellowish skinne, of an acid taste, and somewhat bitter withall and contained in a thinne shell, of a darkish ash-color; with these berries generally in Arabia and Egipt, and in other places of the Turkes Dominions, they make a decoction or drinke, which is in the stead of Wine to them, and generally sold in all their tappe houses, called by the name of Caova; Paludanus saith Chaova, and Rauwolfius Chaube.

This drinke hath many good physical properties therein; for it strengthened a week stomacke, helpeth digestion, and the tumors and obstructions of the liver and spleene, being drunke fasting for some time together.

In 1650, a certain Jew from Lebanon, in some accounts Jacob or Jacobs by name, in others Jobson[62], opened "at the Angel in the parish of St. Peter in the East", Oxford, the earliest English coffee house and "there it [coffee] was by some who delighted in noveltie, drank". Chocolate was also sold at this first coffee house.

Authorities differ, but the confusion as to the name of the coffee-house keeper may have arisen from the fact that there were two—Jacobs, who began in 1650; and another, Cirques Jobson, a Jewish Jacobite, who followed him in 1654.

The drink at once attained great favor among the students. Soon it was in such demand that about 1655 a society of young students encouraged one Arthur Tillyard, "apothecary and Royalist," to sell "coffey publickly in his house against All Soules College." It appears that a club composed of admirers of the young Charles met at Tillyard's and continued until after the Restoration. This Oxford Coffee Club was the start of the Royal Society.

Jacobs removed to Old Southhampton Buildings, London, where he was in 1671.

Meanwhile, the first coffee house in London had been opened by Pasqua Rosée in 1652; and, as the remainder of the story of coffee's rise and fall in England centers around the coffee houses of old London, we shall reserve it for a separate chapter.

From the seventh edition of Sandys' Travels, London, 1673

Of course, the coffee-house idea, and the use of coffee in the home, quickly spread to other cities in Great Britain; but all the coffee houses were patterned after the London model. Mol's coffee house at Exeter, Devonshire, which is pictured on page 41, was one of the first coffee houses established in England, and may be regarded as typical of those that sprang up in the provinces. It had previously been a noted club house; and the old hall, beautifully paneled with oak, still displays the arms of noted members. Here Sir Walter Raleigh and congenial friends regaled themselves with smoking tobacco. This was one of the first places where tobacco was smoked in

Comments (0)