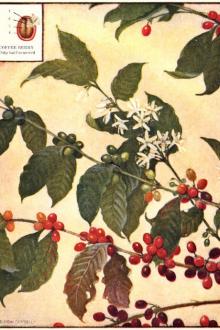

All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖». Author William H. Ukers

Meanwhile, in 1672, one Pascal, an Armenian, first sold coffee publicly in Paris. Pascal, who, according to one account, was brought to Paris by Soliman Aga, offered the beverage for sale from a tent, which was also a kind of booth, in the fair of St.-Germain, supplemented by the service of Turkish waiter boys, who peddled it among the crowds from small cups on trays. The fair was held during the first two months of spring, in a large open plot just inside the walls of Paris and near the Latin Quarter. As Pascal's waiter boys circulated through the crowds on those chilly days the fragrant odor of freshly made coffee brought many ready sales of the steaming beverage; and soon visitors to the fair learned to look for the "little black" cupful of cheer, or petit noir, a name that still endures.

When the fair closed, Pascal opened a small coffee shop on the Quai de l'École, near the Pont Neuf; but his frequenters were of a type who preferred the beers and wines of the day, and coffee languished. Pascal continued, however, to send his waiter boys with their large coffee jugs, that were heated by lamps, through the streets of Paris and from door to door. Their cheery cry of "café! café!" became a welcome call to many a Parisian, who later missed his petit noir when Pascal gave up and moved on to London, where coffee drinking was then in high favor.

Lacking favor at court, coffee's progress was slow. The French smart set clung to its light wines and beers. In 1672, Maliban, another Armenian, opened a coffee house in the rue Bussy, next to the Metz tennis court near St.-Germain's abbey. He supplied tobacco also to his customers. Later he went to Holland, leaving his servant and partner, Gregory, a Persian, in charge. Gregory moved to the rue Mazarine, to be near the Comédie Française. He was succeeded in the business by Makara, another Persian, who later returned to Ispahan, leaving the coffee house to one Le Gantois, of Liége.

About this period there was a cripple boy from Candia, known as le Candiot, who began to cry "coffee!" in the streets of Paris. He carried with him a coffee pot of generous size, a chafing-dish, cups, and all other implements necessary to his trade. He sold his coffee from door to door at two sous per dish, sugar included.

From a Seventeenth-Century Print

A Levantine named Joseph also sold coffee in the streets, and later had several coffee shops of his own. Stephen, from Aleppo, next opened a coffee house on Pont au Change, moving, when his business prospered, to more pretentious quarters in the rue St.-André, facing St.-Michael's bridge.

From a rare water color

All these, and others, were essentially the Oriental style of coffee house of the lower order, and they appealed principally to the poorer classes and to foreigners. "Gentlemen and people of fashion" did not care to be seen in this type of public house. But when the French merchants began to set up, first at St.-Germain's fair, "spacious apartments in an elegant manner, ornamented with tapestries, large mirrors, pictures, marble tables, branches for candles, magnificent lustres, and serving coffee, tea, chocolate, and other refreshments", they were soon crowded with people of fashion and men of letters.

In this way coffee drinking in public acquired a badge of respectability. Presently there were some three hundred coffee houses in Paris. The principal coffee men, in addition to plying their trade in the city, maintained coffee rooms in St.-Germain's and St.-Laurence's fairs. These were frequented by women as well as men.

The Progenitor of the Real Parisian Café

It was not until 1689, that there appeared in Paris a real French adaptation of the Oriental coffee house. This was the Café de Procope, opened by François Procope (Procopio Cultelli, or Cotelli) who came from Florence or Palermo. Procope was a limonadier (lemonade vender) who had a royal license to sell spices, ices, barley water, lemonade, and other such refreshments. He early added coffee to the list, and attracted a large and distinguished patronage.

Procope, a keen-witted merchant, made his appeal to a higher class of patrons than did Pascal and those who first followed him. He established his café directly opposite the newly opened Comédie Française, in the street then known as the rue des Fossés-St.-Germain, but now the rue de l'Ancienne Comédie. A writer of the period has left this description of the place: "The Café de Procope ... was also called the Antre [cavern] de Procope, because it was very dark even in full day, and ill-lighted in the evenings; and because you often saw there a set of lank, sallow poets, who had somewhat the air of apparitions."

Because of its location, the Café de Procope became the gathering place of many noted French actors, authors, dramatists, and musicians of the eighteenth century. It was a veritable literary salon. Voltaire was a constant patron; and until the close of the historic café, after an existence of more than two centuries, his marble table and chair were among the precious relics of the coffee house. His favorite drink is said to have been a mixture of coffee and chocolate. Rousseau, author and philosopher; Beaumarchais, dramatist and financier; Diderot, the encyclopedist; Ste.-Foix, the abbé of Voisenon; de Belloy, author of the Siege of Callais; Lemierre, author of Artaxerce; Crébillon; Piron; La Chaussée; Fontenelle; Condorcet; and a host of lesser lights in the French arts, were habitués of François Procope's modest coffee saloon near the Comédie Française.

Naturally, the name of Benjamin Franklin, recognized in Europe as one of the world's foremost thinkers in the days of the American Revolution, was often spoken over the coffee cups of Café de Procope; and when the distinguished American died in 1790, this French coffee house went into deep mourning "for the great friend of republicanism." The walls, inside and out, were swathed in black bunting, and the statesmanship and scientific attainments of Franklin were acclaimed by all frequenters.

The Café de Procope looms large in the annals of the French Revolution. During the turbulent days of 1789 one could find at the tables, drinking coffee or stronger beverages, and engaged in debate over the burning questions of the hour, such characters as Marat, Robespierre, Danton, Hébert, and Desmoulins. Napoleon Bonaparte, then a poor artillery officer seeking a commission, was also there. He busied himself largely in playing chess, a favorite recreation of the early Parisian coffee-house patrons. It is related that François Procope once compelled young Bonaparte to leave his hat for security while he sought money to pay his coffee score.

After the Revolution, the Café de Procope lost its literary prestige and sank to the level of an ordinary restaurant. During the last half of the nineteenth century, Paul Verlaine, bohemian, poet, and leader of the symbolists, made the Café de Procope his haunt; and for a time it regained some of its lost popularity. The Restaurant Procope still survives at 13 rue de l'Ancienne Comédie.

History records that, with the opening of the Café de Procope, coffee became firmly established in Paris. In the reign of Louis XV there were 600 cafés in Paris. At the close of the eighteenth century there were more than 800. By 1843 the number had increased to more than 3000.

The Development of the Cafés

Coffee's vogue spread rapidly, and many cabaréts and famous eating houses began to add it to their menus. Among these was the Tour d'Argent (silver tower), which had been opened on the Quai de la Tournelle in 1582, and speedily became Paris's most fashionable restaurant. It still is one of the chief attractions for the epicure, retaining the reputation for its cooking that drew a host of world leaders, from Napoleon to Edward VII, to its quaint interior.

From an engraving by Bosredon

Another tavern that took up coffee after Procope, was the Royal Drummer, which Jean Ramponaux established at the Courtille des Porcherons and which followed Magny's. His hostelry rightly belongs to the tavern class, although coffee had a prominent place on its menu. It became notorious for excesses and low-class vices during the reign of Louis XV, who was a frequent visitor. Low and high were to be found in Ramponaux's cellar, particularly when some especially wild revelry was in prospect. Marie Antoinette once declared she had her most enjoyable time at a wild farandole in the Royal Drummer. Ramponaux was taken to its heart by fashionable Paris; and his name was used as a trade mark on furniture, clothes, and foods.

From a drawing by Rétif de la Bretonne

The popularity of Ramponaux's Royal Drummer is attested by an inscription on an early print showing the interior of the café. Translated, it reads:

The pleasures of ease untroubled to taste,

The leisure of home to enjoy without haste,

Perhaps a few hours at Magny's to waste,

Ah, that was the old-fashioned way!

Today all our laborers, everyone knows,

Go running away ere the working hours close,

And why? They must be at Monsieur Ramponaux'!

Behold, the new style of café!

When coffee houses began to crop up rapidly in Paris, the majority centered in the Palais Royal, "that garden spot of beauty, enclosed on three sides by three tiers of galleries," which Richelieu had erected in 1636, under the name of Palais Cardinal, in the reign of Louis XIII. It became known as the Palais Royal in 1643; and soon after the opening of the Café de Procope, it began to blossom out with many attractive coffee stalls, or rooms, sprinkled among the other shops that occupied the galleries overlooking the gardens.

Life In The Early Coffee Houses

Diderot tells in 1760, in his Rameau's Nephew, of the life and frequenters of one of the Palais Royal coffee houses, the Regency (Café de la Régence):

In all weathers, wet or fine, it is my practice to go toward five o'clock in the evening to take a turn in the Palais Royal.... If the weather is too cold or too wet I take shelter in the Regency coffee house. There I amuse myself by looking on while they play chess. Nowhere in the world do they play chess as skillfully as in Paris and nowhere in Paris as they do at this coffee house; 'tis here you see Légal the profound, Philidor the subtle, Mayot the solid; here you see the most astounding moves, and listen to the sorriest talk, for if a man be at once a wit and a great chess player, like Légal, he may also be a great chess player and a sad simpleton, like Joubert and Mayot.

The beginnings of the Regency coffee house are associated with the legend that Lefévre, a Parisian, began peddling coffee in the streets of Paris about the time Procope opened his café in 1689. The story has it that Lefévre later opened a café near the Palais Royal, selling it in 1718 to one Leclerc, who named it the Café de la Régence,

Comments (0)