All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖». Author William H. Ukers

The purpose of his study was to determine both qualitatively and quantitatively the effect of caffein on a wide range of mental and motor processes, by studying the performance of a considerable number of individuals for a long period of time, under controlled conditions; to study the way in which this influence is modified by such factors as the age, sex, weight, idiosyncrasy, and previous caffein habits of the subjects, and the degree to which it depends on the amount of the dose and the time and conditions of its administration; and to investigate the influence of caffein on the general health, quality and amount of sleep, and food habits of the individual tested.

To obtain this information the chief tests employed were the steadiness, tapping, coordination, typewriting, color-naming, calculations, opposites, cancellation, and discrimination tests, the familiar size-weight illusion, quality and amount of sleep, and general health and feeling of well-being. A brief review of the results of these tests is given in the tabular summary.

From these Hollingworth concluded that caffein influenced all the tests in a given group in much the same way. The effect on motor processes comes quickly and is transient, while the effect on higher mental processes comes more slowly and is more persistent. Whether this result is due to quicker reaction on the part of motor-nerve centers, or whether it is due to a direct peripheral effect on the muscle tissue is uncertain, but the indications are that caffein has a direct action on the muscle tissue, and that this effect is fairly rapid in appearance. The two principal factors which seem to modify the degree of caffein influence are body weight and presence of food in the stomach at the time of ingestion of the caffein. In practically all of the tests the magnitude of the caffein influence varied inversely with the body weight, and was most marked when taken on an empty stomach or without food substance. This variance in action was also true for both the quality and amount of sleep, and seemed to be accentuated when taken on successive days; but it did not appear to depend on the age, sex, or previous caffein habits of the individual. Those who had given up the use of caffein-containing beverages during the experiment did not report any craving for the drinks as such, but several expressed a feeling of annoyance at not having some sort of a warm drink for breakfast.

It is interesting to note that he also found a complete absence of any trace of secondary depression or of any sort of secondary reaction consequent upon the stimulation which was so strikingly present in many of the tests. The production of an increased capacity for work was clearly demonstrated, the same being a genuine drug effect, and not merely the effect of excitement, interest, sensory stimulation, expectation, or suggestion. However, this study does not show whether this increased capacity comes from a new supply of energy introduced or rendered available by the drug action, or whether energy already available comes to be employed more effectively, or whether fatigue sensations are weakened and the individual's standard of performance thereby raised. But they do show that from a standpoint of mental and productive physical efficiency "the widespread consumption of caffeinic beverages, even under circumstances in which and by individuals for whom the use of other drugs is stringently prohibited or decried, is justified."

Conclusion

Brief summarization of the information available on the pharmacology of coffee indicates that it should be used in moderation, particularly by children, the permissible quantity varying with the individual and ascertainable only through personal observation. Used in moderation, it will prove a valuable stimulant increasing personal efficiency in mental and physical labor. Its action in the alimentary régime is that of an adjuvant food, aiding digestion, favoring increased flow of the digestive juices, promoting intestinal peristalsis, and not tanning any portion of the digestive organs. It reacts on the kidneys as a diuretic, and increases the excretion of uric acid, which, however, is not to be taken as evidence that it is harmful in gout. Coffee has been indicated as a specific for various diseases, its functions therein being the raising and sustaining of low vitalities. Its effect upon longevity is virtually nil. A small proportion of humans who are very nervous may find coffee undesirable; but sensible consumption of coffee by the average, normal, non-neurasthenic person will not prove harmful but beneficial.

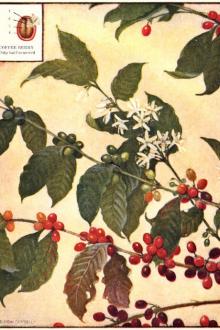

The geographical distribution of the coffees grown in North America, Central America, South America, the West India Islands, Asia, Africa, the Pacific Islands, and the East Indies—A statistical study of the distribution of the principal kinds—A commercial coffee chart of the world's leading growths, with market names and general trade characteristics

A study of the geographical distribution of the coffee tree shows that it is grown in well-defined tropical limits. The coffee belt of the world lies between the tropic of cancer and the tropic of capricorn. The principal coffee consuming countries are nearly all to be found in the north temperate zone, between the tropic of cancer and the arctic circle.

The leading commercial coffees of the world are listed in the accompanying commercial coffee chart, which shows at a glance their general trade character. The cultural methods of the producing countries are discussed in chapter XX; statistics in chapter XXII; and the trade characteristics, in detail, in chapter XXIV, which considers also countries and coffees not so important in a commercial sense. Mexico is the principal producing country in the northern part of the western continent, and Brazil in the southern part. In Africa, the eastern coast furnishes the greater part of the supply; while in Asia, the Netherlands Indies, British India, and Arabia lead.

Within the last two decades there has been an expansion of the production areas in South America, Africa, and in southeastern Asia; and a contraction in British India and the Netherlands Indies.

The Shifting Coffee Currents of the World

Seldom does the coffee drinker realize how the ends of the earth are drawn upon to bring the perfected beverage to his lips. The trail that ends in his breakfast cup, if followed back, would be found to go a devious and winding way, soon splitting up into half-a-dozen or more straggling branches that would lead to as many widely scattered regions. If he could mount to a point where he could enjoy a bird's-eye view of these and a hundred kindred trails, he would find an intricate criss-cross of streamlets and rivers of coffee forming a tangled pattern over the tropics and reaching out north and south to all civilized countries. This would be a picture of the coffee trade of the world.

It would be a motion picture, with the rivulets swelling larger at certain seasons, but seldom drying up entirely at any time. In the main the streamlets and rivers keep pretty much the same direction and volume one year after another, but then there is also a quiet shifting of these currents. Some grow larger, and others diminish gradually until they fade out entirely. In one of the regions from which they take their source a tree disease may cause a decline; in another, a hurricane may lay the industry low at one quick stroke; and in still another, a rival crop may drain away the life-blood of capital. But for the most part, when times are normal, the shift is gradual; for international trade is conservative, and likes to run where it finds a well-worn channel.

In recent times, of course, the big disturbing element in the coffee trade was the World War. Whole countries were cut out of the market, shipping was drained away from every sea lane, stocks were piled high in exporting ports, prices were fixed, imports were sharply restricted, and the whole business of coffee trading was thrown out of joint. To what extent has the world returned to normal in this trade? Were the stoppages in trade merely temporary suspensions, or are they to prove permanent? How are the old, long-worn channels filling up again, now that the dams have been taken away?

We are now far enough removed from the war to begin to answer these questions. We find our answer in the export figures of the chief producing countries, which for the most part are now available in detail for one or two post-war years. These figures are given in the tables below; and for comparison, there are also given figures showing the distribution of exports in 1913 and in an earlier year near the beginning of the century. These figures, of course, do not necessarily give an accurate index to normal trade; as in any given year some abnormal happening, such as an exceptionally large crop or a revolution, may affect exports drastically as compared with years before and after. But normally the proportions of a country's exports going to its various customers are fairly constant one year after another, and can be taken for any given year as showing approximately the coffee currents of that period.

The figures following are for the calendar year unless the fiscal year is indicated. Where figures could not be obtained from the original statistical publications, they have been supplied as far as possible from consular reports.

Brazil. The war naturally increased the dependence of Brazil on its chief customer, and the proportion of the total crop coming to this country since the war has continued to be large. Shipments to United States ports in 1920 represented about fifty-four percent of the total exports. Figures for that year indicate also that France and Belgium were working back to their normal trade; but that Spain, Great Britain, and the Netherlands were taking much less coffee than in the year just before the war. Germany was buying strongly again, her purchases of 72,000,000 pounds being about half as much as in 1913. Shipments to Italy were four times as heavy as in 1913. The natural return to normal was much interfered with by speculation and valorization. Brazil seems to have come through the cataclysmic period of the war in better style than might have been expected.

Coffee Exports from Brazil Exported to 1900

Pounds 1913

Pounds 1920

Pounds United States 566,686,345 650,071,337 826,425,340 France 78,408,862 244,295,282 203,694,212 Great Britain 6,442,739 32,559,715 9,597,378 Germany 235,131,881 246,767,144 72,196,934 Aus.-Hungary 71,696,556 134,495,310 Netherlands 102,711,887 196,169,240 49,760,767 Italy 17,559,107 31,364,656 132,543,798 Spain 868,617 14,407,906 6,057,833 Belgium 41,500,638 58,858,562 42,309,469 Other countries 59,432,882 145,896,327 181,796,919 —————— —————— —————— Total 1,180,439,514 1,754,885,479 1,524,382,650

The 1900 figures are for the ports of Rio, Santos, Bahia, and Victoria.

"Other countries" in 1913 included Argentina, 32,941,182 pounds; Sweden, 28,045,737 pounds; Cape Colony, 15,930,731 pounds; Denmark, 6,252,931 pounds. In 1920 they included Argentina, 37,736,498 pounds; Sweden, 51,026,591 pounds; Denmark, 18,764,483 pounds; Cape Colony, 26,936,653 pounds.

Venezuela. Venezuela's coffee trade was deeply affected by the war; both because the Germans were prominent in the industry, and because the regular shipping service to Europe was discontinued. Large amounts of coffee were piled up at the ports and elsewhere; and when the restrictions were swept away in 1919, an abnormal exportation resulted. Although Germany had been one of the chief buyers before the war, Venezuela was by no means dependent on the German market. In fact, her combined shipments to France and the United States, just before the war, were three times as great as her exports to Germany. These two countries took two-thirds of her total exports in 1920. Spain and the Netherlands were also prominent buyers.

Comments (0)