All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (interesting novels in english TXT) 📖». Author William H. Ukers

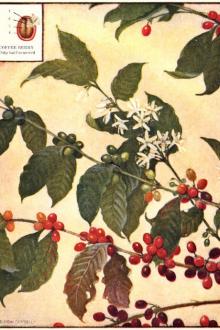

Coffee planters combat pests and diseases principally with sprays, as in other lines of advanced arboriculture. It is a constant battle, especially on the large commercial plantations, and constitutes a large item on the expense sheet.

Cultivation by Countries

Coffee-cultivation methods vary somewhat in detail in the different producing countries. The foregoing description covers the underlying principles in practise throughout the world; while the following is intended to show the local variations in vogue in the principal countries of production, together with brief descriptions of the main producing districts, the altitudes, character of soil, climate, and other factors that are peculiar to each country. In general, they are considered in the order of their relative importance as producing countries.

Brazil. In Brazil, the Giant of South America, and the world's largest coffee producer, the methods of cultivation naturally have reached a high point of development, although the soil and the climate were not at first regarded as favorable. The year 1723 is generally accepted as the date of the introduction of the coffee plant into Brazil from French Guiana. Coffee planting was slow in developing, however, until 1732, when the governor of the states of Pará and Maranhao urged its cultivation. Sixteen years later, there were 17,000 trees in Pará. From that year on, slow but steady progress was made; and by 1770, an export trade had been begun from the port of Pará to countries in Europe.

The spread of the industry began about this time. The coffee tree was introduced into the state of Rio de Janeiro in 1770. From there its cultivation was gradually extended into the states of São Paulo, Minãs Geraes, Bahia, and Espirito Santo, which have become the great coffee-producing sections of Brazil. The cultivation of the plant did not become especially noteworthy until the third decade of the nineteenth century. Large crops were gathered in the season of 1842–43; and by the middle of the century, the plantations were producing annually more than 2,000,000 bags.

Photograph by Courtesy of J. Aron & Co.

Brazil's commercial coffee-growing region has an estimated area of approximately 1,158,000 square miles, and extends from the river Amazon to the southern border of the state of São Paulo, and from the Atlantic coast to the western boundary of the state of Matto Grosso. This area is larger than that section of the United States lying east of the Mississippi River, with Texas added. In every state of the republic, from Ceará in the north to Santa Catharina in the south, the coffee tree can be cultivated profitably; and is, in fact, more or less grown in every state, if only for domestic use. However, little attention is given to coffee-growing in the north, except in the state of Pernambuco, which has only about 1,500,000 trees, as compared, with the 764,000,000 trees of São Paulo in 1922.

The chief coffee-growing plantations in Brazil are situated on plateaus seldom less than 1,800 feet above sea-level, and ranging up to 4,000 feet. The mean annual temperature is approximately 70° F., ranging from a mean of 60.8° in winter to a mean of 72° in summer. The temperature has been known, however, to register 32° in winter and 97.7° in summer.

While coffee trees will grow in almost any part of Brazil, experience indicates that the two most fertile soils, the terra roxa and the massape, lie in the "coffee belts." The terra roxa is a dark red earth, and is practically confined to São Paulo, and to it is due the predominant coffee productivity of that state. Massape is a yellow, dark red—or even black—soil, and occurs more or less contiguous to the terra roxa. With a covering of loose sand, it makes excellent coffee land.

Brazil planters follow the nursery-propagated method of planting, and cultivate, prune, and spray their trees liberally. Transplanting is done in the months from November to February.

Coffee-growing profits have shown a decided falling off in Brazil in recent years. In 1900 it was not uncommon for a coffee estate to yield an annual profit of from 100 to 250 percent. Ten years later the average returns did not exceed twelve percent.

FAZENDA GUATAPARA, SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL, WITH 800,000 TREES IN BEARING

In Brazil's coffee belt there are two seasons—the wet, running from September to March; and the dry, running from April to August. The coffee trees are in bloom from September to December. The blossoms last about four days, and are easily beaten off by light winds or rains. If the rains or winds are violent, the green berries may be similarly destroyed; so that great damage may be caused by unseasonable rains and storms.

The harvest usually begins in April or May, and extends well into the dry season. Even in the picking season, heavy rains and strong winds—especially the latter—may do considerable damage; for in Brazil shade trees and wind-breaks are the exception.

Approximately twenty-five percent of the São Paulo plantations are cultivated by machinery. A type of cultivator very common is similar to the small corn-plow used in the United States. The Planet Junior, manufactured by a well known United States agricultural-machinery firm, is the most popular cultivator. It is drawn by a small mule, with a boy to lead it, and a man to drive and to guide the plow.

Copyright by Brown & Dawson.

The preponderance of the coffee over other industries in São Paulo is shown in many ways. A few years ago the registration of laborers in all industries was about 450,000; and of this total, 420,000 were employed in the production and transportation of coffee alone. Of the capital invested in all industries, about eighty-five percent was in coffee production and commerce, including the railroads that depended upon it directly. An estimated value of $482,500,000 was placed upon the plantations in the state, including land, machinery, the residences of owners, and laborers' quarters.

In all Brazil, there are approximately 1,200,000,000 coffee trees. The number of bearing coffee trees in São Paulo alone increased from 735,000,000 in 1914–15 to 834,000,000 in 1917–18. The crop in 1917–18 was 1,615,000,000 pounds, one of the largest on record. In the agricultural year of 1922–23 there were 764,969,500 coffee trees in bearing in São Paulo, and in São Paulo, Minãs, and Parana, 824,194,500.

Photograph by Courtesy of J. Aron & Co.

Plantations having from 300,000 to 400,000 trees are common. One plantation near Ribeirao Preto has 5,000,000 trees, and requires an army of 6,000 laborers to work it. Another planter owns thirty-two adjacent plantations containing, in all, from 7,500,000 to 8,000,000 coffee trees and gives employment to 8,000 persons. There are fifteen plantations having more than 1,000,000 trees each, and five of these have more than 2,000,000 trees each. In the municipality of Ribeirao Preto there were 30,000,000 trees in 1922.

Showing coffee trees and laborers' houses in the middle distance at right

Photograph by Courtesy of J. Aron & Co.

The largest coffee plantations in the world are the Fazendas Dumont and the Fazendas Schmidt. The Fazendas Dumont were valued, in 1915, in cost of land and improvements, at $5,920,007; and since those figures were given out, the value of the investment has much increased. Of the various Fazendas Schmidt, the largest, owned by Colonel Francisco Schmidt, in 1918 had 9,000,000 trees with an annual yield of 200,000 bags, or 26,400,000 pounds, of coffee. Other large plantations in São Paulo with a million or more trees, are the Companhia Agricola Fazenda Dumont, 2,420,000 trees; Companhia São Martinho, 2,300,000 trees; Companhia Dumont, 2,000,000 trees; São Paulo Coffee Company, 1,860,000 trees; Christiana Oxorio de Oliveira, 1,790,000 trees; Companhia Guatapara, 1,550,000 trees; Dr. Alfredo Ellis, 1,271,000 trees; Companhia Agricola Araqua, 1,200,000 trees; Companhia Agricola Ribeirao Preto, 1,138,000 trees; Rodriguez Alves Irmaos, 1,060,000 trees; Francisca Silveira do Val, 1,050,000 trees; Luiza de Oliveira Azevedo, 1,045,000 trees; and the Companhia Caféeria São Paulo, 1,000,000 trees.

The average annual yield in São Paulo is estimated at from 1,750 to 4,000 pounds from a thousand trees, while in exceptional instances it is said that as much as 6,000 pounds per 1,000 trees have been gathered. Differences in local climatic conditions, in ages of trees, in richness of soil, and in the care exercised in cultivation, are given as the reasons for the wide variation.

The oldest coffee-growing district in São Paulo is Campinas. There are 136 others.

Bahia coffee is not so carefully cultivated and harvested as the Santos coffee. The introduction of capital and modern methods would do much for Bahia, which has the advantage of a shorter haul to the New York and the European markets.

On the average, something like seventy percent of the world's coffee crop is grown in Brazil, and two-thirds of this is produced in São Paulo. Coffee culture in many districts of São Paulo has been brought to the point of highest development; and yet its product is essentially a quantity, not a quality, one.

Colombia. In Colombia, coffee is the principal crop grown for export. It is produced in nearly all departments at elevations ranging from 3,500 feet to 6,500 feet. Chief among the coffee-growing departments are Antioquia (capital, Medellin); Caldas (capital, Manizales); Magdalena (capital, Santa Marta); Santander (capital, Bucaramanga); Tolima (capital, Ibague); and the Federal District (capital, Bogota). The department of Cundinamarca produces a coffee that is counted one of the best of Colombian grades. The finest grades are grown in the foot-hills of the Andes, in altitudes from 3,500 to 4,500 feet above sea level.

The running water carries the picked coffee berries to pulpers and washing tanks

Coffee Picking and Field Transport Coffee Picking and Field Transport

COFFEE CULTURE IN SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL

A NEAR VIEW OF A HEAVILY LADEN COFFEE TREE ON A BOGOTA PLANTATION

A NEAR VIEW OF A HEAVILY LADEN COFFEE TREE ON A BOGOTA PLANTATION

Picking Coffee on a Bogota Plantation Picking Coffee on a Bogota Plantation

Methods of planting, cultivation, gathering, and preparing the Colombian coffee crop for the market are substantially those that are common in all coffee-producing countries, although they differ in some small particulars. About 700 trees are usually planted to the acre, and native trees furnish the necessary shade. The average yield is one pound per tree per year.

While Coffea arabica has been mostly cultivated in Colombia, as in the other countries of South America, the liberica variety has not been neglected. Seeds of the liberica tree were planted here soon after 1880, and were moderately successful. Since 1900, more attention has been given to liberica, and attempts have been made to grow it upon banana and rubber plantations, which seem to provide all the shade protection that is needed. Liberica coffee trees begin to bear in their third year. From the fifth year, when a crop of about 650 pounds to the acre can reasonably be expected, the productiveness steadily increases until after fifteen or sixteen years, when a maximum of over one thousand pounds an acre is attained.

Antioquia is the largest coffee producing

Comments (0)