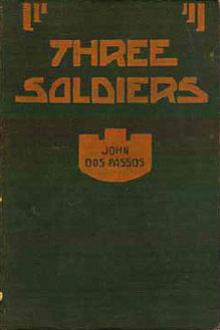

Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (best e book reader android .txt) 📖

- Author: John Dos Passos

- Performer: -

Book online «Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (best e book reader android .txt) 📖». Author John Dos Passos

“And why should you eat a lamp—chimney, Bob?” came a hoarse voice beside them.

Andrews looked up into a round, white face with large grey eyes hidden behind thick steel-rimmed spectacles. Except for the eyes, the face had a vaguely Chinese air.

“Hello, Heinz! Mr. Andrews, Mr. Heineman,” said Henslowe.

“Glad to meet you,” said Heineman in a jovially hoarse voice. “You guys seem to be overeating, to reckon by the way things are piled up on the table.” Through the hoarseness Andrews could detect a faint Yankee tang in Heineman’s voice.

“You’d better sit down and help us,” said Henslowe.

“Sure….D’you know my name for this guy?” He turned to Andrews…. “Sinbad!”

“Sinbad was in bad in Tokio and Rome, In bad in Trinidad And twice as bad at home.”

He sang the words loudly, waving a bread stick to keep time.

“Shut up, Heinz, or you’ll get us run out of here the way you got us run out of the Olympia that night.”

They both laughed.

“An’ d’you remember Monsieur Le Guy with his coat?

“Do I? God!” They laughed till the tears ran down their cheeks. Heineman took off his glasses and wiped them. He turned to Andrews.

“Oh, Paris is the best yet. First absurdity: the Peace Conference and its nine hundred and ninety-nine branches. Second absurdity: spies. Third: American officers A.W.O.L. Fourth: The seven sisters sworn to slay.” He broke out laughing again, his chunky body rolling about on the chair.

“What are they?”

“Three of them have sworn to slay Sinbad, and four of them have sworn to slay me…. But that’s too complicated to tell at lunch time…. Eighth: there are the lady relievers, Sinbad’s specialty. Ninth: there’s Sinbad….”

“Shut up, Heinz, you’re getting me maudlin,” spluttered Henslowe.

“O Sinbad was in bad all around,”

chanted Heineman. “But no one’s given me anything to drink,” he said suddenly in a petulant voice. “Garcon, une bouteille de Macon, pour un Cadet de Gascogne…. What’s the next? It ends with vergogne. You’ve seen the play, haven’t you? Greatest play going…. Seen it twice sober and seven other times.”

“Cyrano de Bergerac?”

“That’s it. Nous sommes les Cadets de Gasgogne, rhymes with ivrogne and sans vergogne…. You see I work in the Red Cross…. You know Sinbad, old Peterson’s a brick…. I’m supposed to be taking photographs of tubercular children at this minute…. The noblest of my professions is that of artistic photographer…. Borrowed the photographs from the rickets man. So I have nothing to do for three months and five hundred francs travelling expenses. Oh, children, my only prayer is ‘give us this day our red worker’s permit’ and the Red Cross does the rest.” Heineman laughed till the glasses rang on the table. He took off his glasses and wiped them with a rueful air.

“So now I call the Red Cross the Cadets!” cried Heineman, his voice a thin shriek from laughter.

Andrews was drinking his coffee in little sips, looking out of the window at the people that passed. An old woman with a stand of flowers sat on a small cane chair at the corner. The pink and yellow and blue-violet shades of the flowers seemed to intensify the misty straw color and azured grey of the wintry sun and shadow of the streets. A girl in a tight-fitting black dress and black hat stopped at the stand to buy a bunch of pale yellow daisies, and then walked slowly past the window of the restaurant in the direction of the gardens. Her ivory face and slender body and her very dark eyes sent a sudden flush through Andrews’s whole frame as he looked at her. The black erect figure disappeared in the gate of the gardens.

Andrews got to his feet suddenly.

“I’ve got to go,” he said in a strange voice…. “I just remember a man was waiting for me at the School Headquarters.”

“Let him wait.”

“Why, you haven’t had a liqueur yet,” cried Heineman.

“No…but where can I meet you people later?”

“Cafe de Rohan at five…opposite the Palais Royal.”

“You’ll never find it.”

“Yes I will,” said Andrews.

“Palais Royal metro station,” they shouted after him as he dashed out of the door.

He hurried into the gardens. Many people sat on benches in the frail sunlight. Children in bright-colored clothes ran about chasing hoops. A woman paraded a bunch of toy balloons in carmine and green and purple, like a huge bunch of parti-colored grapes inverted above her head. Andrews walked up and down the alleys, scanning faces. The girl had disappeared. He leaned against a grey balustrade and looked down into the empty pond where traces of the explosion of a Bertha still subsisted. He was telling himself that he was a fool. That even if he had found her he could not have spoken to her; just because he was free for a day or two from the army he needn’t think the age of gold had come back to earth. Smiling at the thought, he walked across the gardens, wandered through some streets of old houses in grey and white stucco with slate mansard roofs and fantastic complications of chimney-pots till he came out in front of a church with a new classic facade of huge columns that seemed toppling by their own weight.

He asked a woman selling newspapers what the church’s name was. “Mais, Monsieur, c’est Saint Sulpice,” said the woman in a surprised tone.

Saint Sulpice. Manon’s songs came to his head, and the sentimental melancholy of eighteenth century Paris with its gambling houses in the Palais Royal where people dishonored themselves in the presence of their stern Catonian fathers, and its billets doux written at little gilt tables, and its coaches lumbering in covered with mud from the provinces through the Porte d’Orleans and the Porte de Versailles; the Paris of Diderot and Voltaire and Jean-Jacques, with its muddy streets and its ordinaries where one ate bisques and larded pullets and souffles; a Paris full of mouldy gilt magnificence, full of pompous ennui of the past and insane hope of the future.

He walked down a narrow, smoky street full of antique shops and old bookshops and came out unexpectedly on the river opposite the statue of Voltaire. The name on the corner was quai Malaquais. Andrews crossed and looked down for a long time at the river. Opposite, behind a lacework of leafless trees, were the purplish roofs of the Louvre with their high peaks and their ranks and ranks of chimneys; behind him the old houses of the quai and the wing, topped by a balustrade with great grey stone urns of a domed building of which he did not know the name. Barges were coming upstream, the dense green water spuming under their blunt bows, towed by a little black tugboat with its chimney bent back to pass under the bridges. The tug gave a thin shrill whistle. Andrews started walking downstream. He crossed by the bridge at the corner of the Louvre, turned his back on the arch Napoleon built to receive the famous horses from St. Marc’s,—a pinkish pastry-like affair—and walked through the Tuileries which were full of people strolling about or sitting in the sun, of doll-like children and nursemaids with elaborate white caps, of fluffy little dogs straining at the ends of leashes. Suddenly a peaceful sleepiness came over him. He sat down in the sun on a bench, watching, hardly seeing them, the people who passed to and fro casting long shadows. Voices and laughter came very softly to his ears above the distant stridency of traffic. From far away he heard for a few moments notes of a military band playing a march. The shadows of the trees were faint blue-grey in the ruddy yellow gravel. Shadows of people kept passing and repassing across them. He felt very languid and happy.

Suddenly he started up; he had been dozing. He asked an old man with a beautifully pointed white beard the way to rue du Faubourg St. Honore.

After losing his way a couple of times, he walked listlessly up some marble steps where a great many men in khaki were talking. Leaning against the doorpost was Walters. As he drew near Andrews heard him saying to the man next to him:

“Why, the Eiffel tower was the first piece of complete girder construction ever built…. That’s the first thing a feller who’s wide awake ought to see.”

“Tell me the Opery’s the grandest thing to look at,” said the man next it.

“If there’s wine an’ women there, me for it.”

“An’ don’t forget the song.”

“But that isn’t interesting like the Eiffel tower is,” persisted Walters.

“Say, Walters, I hope you haven’t been waiting for me,” stammered Andrews.

“No, I’ve been waiting in line to see the guy about courses…. I want to start this thing right.”

“I guess I’ll see them tomorrow,” said Andrews.

“Say have you done anything about a room, Andy? Let’s you and me be bunkies.”

“All right…. But maybe you won’t want to room where I do, Walters.”

“Where’s that? In the Latin Quarter?… You bet. I want to see some French life while I am about it.”

“Well, it’s too late to get a room to-day.”

“I’m going to the ‘Y’ tonight anyway.”

“I’ll get a fellow I know to put me up…. Then tomorrow, we’ll see. Well, so long,” said Andrews, moving away.

“Wait. I’m coming with you…. We’ll walk around town together.”

“All right,” said Andrews.

The rabbit was rather formless, very fluffy and had a glance of madness in its pink eye with a black center. It hopped like a sparrow along the pavement, emitting a rubber tube from its back, which went up to a bulb in a man’s hand which the man pressed to make the rabbit hop. Yet the rabbit had an air of organic completeness. Andrews laughed inordinately when he first saw it. The vendor, who had a basket full of other such rabbits on his arm, saw Andrews laughing and drew timidly near to the table; he had a pink face with little, sensitive lips rather like a real rabbit’s, and large frightened eyes of a wan brown.

“Do you make them yourself?” asked Andrews, smiling.

The man dropped his rabbit on the table with a negligent air.

“Oh, oui, Monsieur, d’apres la nature.”

He made the rabbit turn a somersault by suddenly pressing the bulb hard. Andrews laughed and the rabbit man laughed.

“Think of a big strong man making his living that way,” said Walters, disgusted.

“I do it all…de matiere premiere au profit de l’accapareur,” said the rabbit man.

“Hello, Andy…late as hell…. I’m sorry,” said Henslowe, dropping down into a chair beside them. Andrews introduced Walters, the rabbit man took off his hat, bowed to the company and went off, making the rabbit hop before him along the edge of the curbstone.

“What’s happened to Heineman?”

“Here he comes now,” said Henslowe.

An open cab had driven up to the curb in front of the cafe. In it sat Heineman with a broad grin on his face and beside him a woman in a salmon-colored dress, ermine furs and an emerald-green hat. The cab drove off and Heineman, still grinning, walked up to the table.

“Where’s the lion cub?” asked Henslowe.

“They say it’s got pneumonia.”

“Mr. Heineman. Mr. Walters.”

The grin left Heineman’s face; he said: “How do you do?” curtly, cast a furious glance at Andrews and settled himself in a chair.

The sun had set. The sky was full of lilac and bright purple and carmine. Among the deep blue shadows lights were coming

Comments (0)