e than any other of the owner's treasures. It was, curiously enough, to this little heap of literature that Wid Gardner presently turned.

Forgetful of the hour and of his waiting cows, he sat down, a copy in his hands, his face taking on a new sort of light as he read. At times, as lone men will, he broke out into audible soliloquy. Now and again his hand slapped his knee, his eye kindled, he grinned. The pages were ill-printed, showing many paragraphs, apparently of advertising nature, in fine type, sometimes marked with display lines.

Wid turned page after page, grunting as he did so, until at last he tossed the magazine upon the top of the box and so went about his evening chores. Thus the title of the publication was left showing to any observer. The headline was done in large black letters, advising all who might have read that this was a copy of the magazine known as Hearts Aflame.

Curiously enough, on the front page the headline of a certain advertisement showed plainly. I

ched its climax with the insults, and the lethargic spirit woke to life. His sensitiveness, the chief trait of the native, was touched, and while he had had the forbearance to suffer and die under a foreign flag, he had it not when they whom he served repaid his sacrifices with insults and jests. Then he began to study himself and to realize his misfortune. Those who had not expected this result, like all despotic masters, regarded as a wrong every complaint, every protest, and punished it with death, endeavoring thus to stifle every cry of sorrow with blood, and they made mistake after mistake.

The spirit of the people was not thereby cowed, and even though it had been awakened in only a few hearts, its flame nevertheless was surely and consumingly propagated, thanks to abuses and the stupid endeavors of certain classes to stifle noble and generous sentiments. Thus when a flame catches a garment, fear and confusion propagate it more and more, and each shake, each blow, is a blast from the bellows to f

cratching his back with it. When Philip did a doubletake, however, the ear was back to normal size and reposing on its owner's tawny cheek. Rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, he said, "Come on, Zarathustra, we're going for a walk."

He headed for the back door, Zarathustra at his heels. A double door leading off the dining room barred his way and proved to be locked. Frowning, he returned to the living room. "All right," he said to Zarathustra, "we'll go out the front way then."

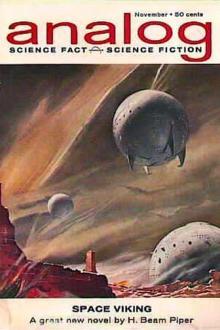

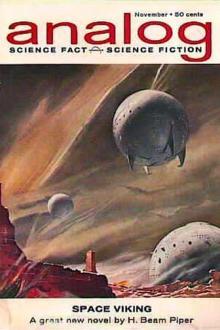

[Illustration]

He walked around the side of the house, his canine companion trotting beside him. The side yard turned out to be disappointing. It contained no roses--green ones, or any other kind. About all it did contain that was worthy of notice was a dog house--an ancient affair that was much too large for Zarathustra and which probably dated from the days when Judith had owned a larger dog. The yard itself was a mess: the grass hadn't been cut all summer, the shrubbery was ragged, and dead leaves lay everywhere

e minutes.

But there had been a clever, good-natured littleFrench teacher who had said to the music-master:

"Zat leetle Crewe. Vat a child! A so ogly beauty!Ze so large eyes! ze so little spirituelle face.Waid till she grow up. You shall see!"

This morning, however, in the tight, smallblack frock, she looked thinner and odder thanever, and her eyes were fixed on Miss Minchinwith a queer steadiness as she slowly advancedinto the parlor, clutching her doll.

"Put your doll down!" said Miss Minchin.

"No," said the child, I won't put her down;I want her with me. She is all I have. She hasstayed with me all the time since my papa died."

She had never been an obedient child. She hadhad her own way ever since she was born, and therewas about her an air of silent determination underwhich Miss Minchin had always felt secretly uncomfortable.And that lady felt even now that perhaps it would beas well not to insist on her point. So she lookedat her as severely as possible.

"Yo

THE LAPIS NIGER.Roma Beata. Maud Howe. Pp. 163, 260.

POMPEY'S THEATER._Rome: The Eternal City_. Clara Erskine Clement. Vol. i, P. 374.Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries. RodolfoLanciani. P. 190.

THE ROMAN FORUM AS IT APPEARS TO-DAY.Roman Holidays and Others. W.D. Howells. P. 96.

POEM.--In the Roman ForumAmelia Josephine Burr. Literary Digest. Vol. xlviii, p. 1130.

THE ROMAN HOUSE

"Here is my religion, here is my race, here are the traces of myforefathers. I cannot express the charm which I find here, and whichpenetrates my heart and my senses."--Cicero: Pro Domo.

THE PLAN OF THE ROMAN HOUSE.Callus. W.A. Becker. P. 237.The Life of the Greeks and Romans. Guhl and Koner. P. 357.The Private Life of the Romans. H.W. Johnston. Chap. vi.Society in Rome under the Caesars. William R. Inge. Chap. x.

THE HEATING AND LIGHTING OF THE HOUSE.The Life

n air.

In the grill-room of the Mena House we meet the poet Shakib, who was then drawing his inspiration from a glass of whiskey and soda. Nay, he was drowning his sorrows therein, for his Master, alas! has mysteriously disappeared.

"I have not seen him for ten days," said the Poet; "and I know not where he is.--If I did? Ah, my friend, you would not then see me here. Indeed, I should be with him, and though he be in the trap of the Young Turks." And some real tears flowed down the cheeks of the Poet, as he spoke.

The Mena House, a charming little Branch of Civilisation at the gate of the desert, stands, like man himself, in the shadow of two terrible immensities, the Sphinx and the Pyramid, the Origin and the End. And in the grill-room, over a glass of whiskey and soda, we presume to solve in few words the eternal mystery. But that is not what we came for. And to avoid the bewildering depths into which we were led, we suggested a stroll on the sands. Here the Poet waxed more eloquent, an

e than any other of the owner's treasures. It was, curiously enough, to this little heap of literature that Wid Gardner presently turned.

Forgetful of the hour and of his waiting cows, he sat down, a copy in his hands, his face taking on a new sort of light as he read. At times, as lone men will, he broke out into audible soliloquy. Now and again his hand slapped his knee, his eye kindled, he grinned. The pages were ill-printed, showing many paragraphs, apparently of advertising nature, in fine type, sometimes marked with display lines.

Wid turned page after page, grunting as he did so, until at last he tossed the magazine upon the top of the box and so went about his evening chores. Thus the title of the publication was left showing to any observer. The headline was done in large black letters, advising all who might have read that this was a copy of the magazine known as Hearts Aflame.

Curiously enough, on the front page the headline of a certain advertisement showed plainly. I

ched its climax with the insults, and the lethargic spirit woke to life. His sensitiveness, the chief trait of the native, was touched, and while he had had the forbearance to suffer and die under a foreign flag, he had it not when they whom he served repaid his sacrifices with insults and jests. Then he began to study himself and to realize his misfortune. Those who had not expected this result, like all despotic masters, regarded as a wrong every complaint, every protest, and punished it with death, endeavoring thus to stifle every cry of sorrow with blood, and they made mistake after mistake.

The spirit of the people was not thereby cowed, and even though it had been awakened in only a few hearts, its flame nevertheless was surely and consumingly propagated, thanks to abuses and the stupid endeavors of certain classes to stifle noble and generous sentiments. Thus when a flame catches a garment, fear and confusion propagate it more and more, and each shake, each blow, is a blast from the bellows to f

cratching his back with it. When Philip did a doubletake, however, the ear was back to normal size and reposing on its owner's tawny cheek. Rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, he said, "Come on, Zarathustra, we're going for a walk."

He headed for the back door, Zarathustra at his heels. A double door leading off the dining room barred his way and proved to be locked. Frowning, he returned to the living room. "All right," he said to Zarathustra, "we'll go out the front way then."

[Illustration]

He walked around the side of the house, his canine companion trotting beside him. The side yard turned out to be disappointing. It contained no roses--green ones, or any other kind. About all it did contain that was worthy of notice was a dog house--an ancient affair that was much too large for Zarathustra and which probably dated from the days when Judith had owned a larger dog. The yard itself was a mess: the grass hadn't been cut all summer, the shrubbery was ragged, and dead leaves lay everywhere

e minutes.

But there had been a clever, good-natured littleFrench teacher who had said to the music-master:

"Zat leetle Crewe. Vat a child! A so ogly beauty!Ze so large eyes! ze so little spirituelle face.Waid till she grow up. You shall see!"

This morning, however, in the tight, smallblack frock, she looked thinner and odder thanever, and her eyes were fixed on Miss Minchinwith a queer steadiness as she slowly advancedinto the parlor, clutching her doll.

"Put your doll down!" said Miss Minchin.

"No," said the child, I won't put her down;I want her with me. She is all I have. She hasstayed with me all the time since my papa died."

She had never been an obedient child. She hadhad her own way ever since she was born, and therewas about her an air of silent determination underwhich Miss Minchin had always felt secretly uncomfortable.And that lady felt even now that perhaps it would beas well not to insist on her point. So she lookedat her as severely as possible.

"Yo

THE LAPIS NIGER.Roma Beata. Maud Howe. Pp. 163, 260.

POMPEY'S THEATER._Rome: The Eternal City_. Clara Erskine Clement. Vol. i, P. 374.Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries. RodolfoLanciani. P. 190.

THE ROMAN FORUM AS IT APPEARS TO-DAY.Roman Holidays and Others. W.D. Howells. P. 96.

POEM.--In the Roman ForumAmelia Josephine Burr. Literary Digest. Vol. xlviii, p. 1130.

THE ROMAN HOUSE

"Here is my religion, here is my race, here are the traces of myforefathers. I cannot express the charm which I find here, and whichpenetrates my heart and my senses."--Cicero: Pro Domo.

THE PLAN OF THE ROMAN HOUSE.Callus. W.A. Becker. P. 237.The Life of the Greeks and Romans. Guhl and Koner. P. 357.The Private Life of the Romans. H.W. Johnston. Chap. vi.Society in Rome under the Caesars. William R. Inge. Chap. x.

THE HEATING AND LIGHTING OF THE HOUSE.The Life

n air.

In the grill-room of the Mena House we meet the poet Shakib, who was then drawing his inspiration from a glass of whiskey and soda. Nay, he was drowning his sorrows therein, for his Master, alas! has mysteriously disappeared.

"I have not seen him for ten days," said the Poet; "and I know not where he is.--If I did? Ah, my friend, you would not then see me here. Indeed, I should be with him, and though he be in the trap of the Young Turks." And some real tears flowed down the cheeks of the Poet, as he spoke.

The Mena House, a charming little Branch of Civilisation at the gate of the desert, stands, like man himself, in the shadow of two terrible immensities, the Sphinx and the Pyramid, the Origin and the End. And in the grill-room, over a glass of whiskey and soda, we presume to solve in few words the eternal mystery. But that is not what we came for. And to avoid the bewildering depths into which we were led, we suggested a stroll on the sands. Here the Poet waxed more eloquent, an