ury of both.

When the French Revolution broke out, it certainly afforded to Mr. Burke an opportunity of doing some good, had he been disposed to it; instead of which, no sooner did he see the old prejudices wearing away, than he immediately began sowing the seeds of a new inveteracy, as if he were afraid that England and France would cease to be enemies. That there are men in all countries who get their living by war, and by keeping up the quarrels of Nations, is as shocking as it is true; but when those who are concerned in the government of a country, make it their study to sow discord and cultivate prejudices between Nations, it becomes the more unpardonable.

With respect to a paragraph in this work alluding to Mr. Burke's having a pension, the report has been some time in circulation, at least two months; and as a person is often the last to hear what concerns him the most to know, I have mentioned it, that Mr. Burke may have an opportunity of contradicting the rumour, if he thinks proper.

ion, and perhaps enabled him to popularize his subject, but for his Satanic contempt for all academic dignitaries and persons in general who thought more of Greek than of phonetics. Once, in the days when the Imperial Institute rose in South Kensington, and Joseph Chamberlain was booming the Empire, I induced the editor of a leading monthly review to commission an article from Sweet on the imperial importance of his subject. When it arrived, it contained nothing but a savagely derisive attack on a professor of language and literature whose chair Sweet regarded as proper to a phonetic expert only. The article, being libelous, had to be returned as impossible; and I had to renounce my dream of dragging its author into the limelight. When I met him afterwards, for the first time for many years, I found to my astonishment that he, who had been a quite tolerably presentable young man, had actually managed by sheer scorn to alter his personal appearance until he had become a sort of walking repudiation of Oxford an

to one of them publicly was already sufficient to set him off as one in imminent need of psychiatrical attention. Belief in them had become a mark of inferiority, like the allied belief in madstones, magic and apparitions.

But though the theology of Christianity had thus sunk to the lowly estate of a mere delusion of the rabble, propagated on that level by the ancient caste of sacerdotal parasites, the ethics of Christianity continued to enjoy the utmost acceptance, and perhaps even more acceptance than ever before. It seemed to be generally felt, in fact, that they simply must be saved from the wreck--that the world would vanish into chaos if they went the way of the revelations supporting them. In this fear a great many judicious men joined, and so there arose what was, in essence, an absolutely new Christian cult--a cult, to wit, purged of all the supernaturalism superimposed upon the older cult by generations of theologians, and harking back to what was conceived to be the pure ethical doc

nd 2 carrots cut fine, 1 bay-leaf, a sprig of thyme and a fewpeppercorns. Pour over 1 cup of vinegar and 1 cup of hot water. Dredgewith flour and let bake in a hot oven. Baste often with the sauce inthe pan until nearly done; then add 1 pint of sour cream and let bakeuntil done. Thicken with flour; boil up and pour over the roast.

14.--Italian Sugar Cakes.

Beat 1-1/2 pounds of sugar and 1/2 pound of butter to a cream; add 4yolks of eggs, a pinch of salt and nutmeg. Stir in 1/2 pound of flour,4 ounces of currants, 2 ounces of chopped almonds, 1 tablespoonful ofcitron and candied orange peel chopped fine. Add the whites beatenstiff and bake in small well-buttered cake-tins until done; then coverwith a thin icing.

15.--Oriental Stewed Prawns.

Clean and pick 3 dozen prawns. Heat some dripping in a large saucepan;add the prawns, 1 chopped onion, salt, pepper and 1 teaspoonful ofcurry-powder. Add 1 pint of stock and let simmer half an hour untiltender. Serve on a border of boiled r

, day by day, so

Christ is able

in heaven now to do what He could not do when He was on earth--to keep in the closest fellowship with every believer throughout the whole world. Glory be to God! You know that text in Ephesians: "He that descended is the same also that ascended, that He might fill all things." Why was my Lord Jesus taken up to heaven away from the life of earth? Because the life of earth is a life confined to localities, but the life in heaven is a life in which there is no limit and no bound and no locality, and Christ was taken up to heaven, that, in the power of God, of the omnipresent God, He might be able to fill every individual here and be with every individual believer.

That is what my heart wants to realize by faith; that is a possibility, that is a promise, that is my birthright, and I want to have it, and I want by the grace of God to say, "Jesus, I will not rest until Thou hast revealed Thyself fully to my soul."

There are often very blessed expe

e matron.

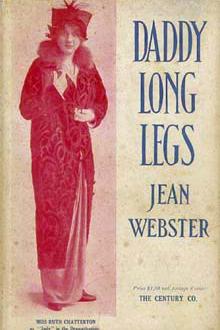

`This gentleman has taken an interest in several of our boys. You remember Charles Benton and Henry Freize? They were both sent through college by Mr.--er--this Trustee, and both have repaid with hard work and success the money that was so generously expended. Other payment the gentleman does not wish. Heretofore his philanthropies have been directed solely towards the boys; I have never been able to interest him in the slightest degree in any of the girls in the institution, no matter how deserving. He does not, I may tell you, care for girls.'

`No, ma'am,' Jerusha murmured, since some reply seemed to be expected at this point.

`To-day at the regular meeting, the question of your future was brought up.'

Mrs. Lippett allowed a moment of silence to fall, then resumed in a slow, placid manner extremely trying to her hearer's suddenly tightened nerves.

`Usually, as you know, the children are not kept after they are sixteen, but an exception was made in your case. You

accustomed to many eyes.

And as each and all of them were warmed without by the sun, so each had a private little sun for her soul to bask in; some dream, some affection, some hobby, at least some remote and distant hope which, though perhaps starving to nothing, still lived on, as hopes will. They were all cheerful, and many of them merry.

They came round by The Pure Drop Inn, and were turning out of the high road to pass through a wicket-gate into the meadows, when one of the women said--

"The Load-a-Lord! Why, Tess Durbeyfield, if there isn't thy father riding hwome in a carriage!"

A young member of the band turned her head at the exclamation. She was a fine and handsome girl--not handsomer than some others, possibly--but her mobile peony mouth and large innocent eyes added eloquence to colour and shape. She wore a red ribbon in her hair, and was the only one of the white company who could boast of such a pronounced adornment. As she looked round Durbeyfield was seen moving alon

THIS book is a slice of intensified historyhistory as I saw it. It does not pretend to be anything but a detailed account of the November Revolution, when the Bolsheviki, at the head of the workers and soldiers, seized the state power of Russia and placed it in the hands of the Soviets.

Naturally most of it deals with Red Petrograd, the capital and heart of the insurrection. But the reader must realize that what took place in Petrograd was almost exactly duplicated, with greater or lesser intensity, at different intervals of time, all over Russia.

In this book, the first of several which I am writing, I must confine myself to a chronicle of those events which I myself observed and experienced, and those supported by reliable evidence; preceded by two chapters briefly outlining the background and causes of the November Revolution. I am aware that these two chapters make difficult reading, but they are essential to an understanding of what follows.

Many questions will suggest themselves to the mind of the reader. What is Bolshevism? What kind of

their respect for the ladies, whom it was their duty to serve. And nearly every other ceremony which has lasted was based on common sense. "Etiquette," as Dr. Brown has said, "with all its littlenesses and niceties, is founded upon a central idea of right and wrong."

The word "courtesy" itself did not come into the language until late (etiquette came even later) and then it was used to describe the polite practices at court. It was wholly divorced from any idea of character, and the most fastidious gentlemen were sometimes the most complete scoundrels. Even the authors of books of etiquette were men of great superficial elegance whose moral standards were scandalously low. One of them, an Italian, was banished from court for having published an indecent poem and wrote his treatise on polite behavior while he was living in enforced retirement in his villa outside the city. It was translated for the edification of the young men of England and France and served as a standard for several generations. Anot

ury of both.

When the French Revolution broke out, it certainly afforded to Mr. Burke an opportunity of doing some good, had he been disposed to it; instead of which, no sooner did he see the old prejudices wearing away, than he immediately began sowing the seeds of a new inveteracy, as if he were afraid that England and France would cease to be enemies. That there are men in all countries who get their living by war, and by keeping up the quarrels of Nations, is as shocking as it is true; but when those who are concerned in the government of a country, make it their study to sow discord and cultivate prejudices between Nations, it becomes the more unpardonable.

With respect to a paragraph in this work alluding to Mr. Burke's having a pension, the report has been some time in circulation, at least two months; and as a person is often the last to hear what concerns him the most to know, I have mentioned it, that Mr. Burke may have an opportunity of contradicting the rumour, if he thinks proper.

ion, and perhaps enabled him to popularize his subject, but for his Satanic contempt for all academic dignitaries and persons in general who thought more of Greek than of phonetics. Once, in the days when the Imperial Institute rose in South Kensington, and Joseph Chamberlain was booming the Empire, I induced the editor of a leading monthly review to commission an article from Sweet on the imperial importance of his subject. When it arrived, it contained nothing but a savagely derisive attack on a professor of language and literature whose chair Sweet regarded as proper to a phonetic expert only. The article, being libelous, had to be returned as impossible; and I had to renounce my dream of dragging its author into the limelight. When I met him afterwards, for the first time for many years, I found to my astonishment that he, who had been a quite tolerably presentable young man, had actually managed by sheer scorn to alter his personal appearance until he had become a sort of walking repudiation of Oxford an

to one of them publicly was already sufficient to set him off as one in imminent need of psychiatrical attention. Belief in them had become a mark of inferiority, like the allied belief in madstones, magic and apparitions.

But though the theology of Christianity had thus sunk to the lowly estate of a mere delusion of the rabble, propagated on that level by the ancient caste of sacerdotal parasites, the ethics of Christianity continued to enjoy the utmost acceptance, and perhaps even more acceptance than ever before. It seemed to be generally felt, in fact, that they simply must be saved from the wreck--that the world would vanish into chaos if they went the way of the revelations supporting them. In this fear a great many judicious men joined, and so there arose what was, in essence, an absolutely new Christian cult--a cult, to wit, purged of all the supernaturalism superimposed upon the older cult by generations of theologians, and harking back to what was conceived to be the pure ethical doc

nd 2 carrots cut fine, 1 bay-leaf, a sprig of thyme and a fewpeppercorns. Pour over 1 cup of vinegar and 1 cup of hot water. Dredgewith flour and let bake in a hot oven. Baste often with the sauce inthe pan until nearly done; then add 1 pint of sour cream and let bakeuntil done. Thicken with flour; boil up and pour over the roast.

14.--Italian Sugar Cakes.

Beat 1-1/2 pounds of sugar and 1/2 pound of butter to a cream; add 4yolks of eggs, a pinch of salt and nutmeg. Stir in 1/2 pound of flour,4 ounces of currants, 2 ounces of chopped almonds, 1 tablespoonful ofcitron and candied orange peel chopped fine. Add the whites beatenstiff and bake in small well-buttered cake-tins until done; then coverwith a thin icing.

15.--Oriental Stewed Prawns.

Clean and pick 3 dozen prawns. Heat some dripping in a large saucepan;add the prawns, 1 chopped onion, salt, pepper and 1 teaspoonful ofcurry-powder. Add 1 pint of stock and let simmer half an hour untiltender. Serve on a border of boiled r

, day by day, so

Christ is able

in heaven now to do what He could not do when He was on earth--to keep in the closest fellowship with every believer throughout the whole world. Glory be to God! You know that text in Ephesians: "He that descended is the same also that ascended, that He might fill all things." Why was my Lord Jesus taken up to heaven away from the life of earth? Because the life of earth is a life confined to localities, but the life in heaven is a life in which there is no limit and no bound and no locality, and Christ was taken up to heaven, that, in the power of God, of the omnipresent God, He might be able to fill every individual here and be with every individual believer.

That is what my heart wants to realize by faith; that is a possibility, that is a promise, that is my birthright, and I want to have it, and I want by the grace of God to say, "Jesus, I will not rest until Thou hast revealed Thyself fully to my soul."

There are often very blessed expe

e matron.

`This gentleman has taken an interest in several of our boys. You remember Charles Benton and Henry Freize? They were both sent through college by Mr.--er--this Trustee, and both have repaid with hard work and success the money that was so generously expended. Other payment the gentleman does not wish. Heretofore his philanthropies have been directed solely towards the boys; I have never been able to interest him in the slightest degree in any of the girls in the institution, no matter how deserving. He does not, I may tell you, care for girls.'

`No, ma'am,' Jerusha murmured, since some reply seemed to be expected at this point.

`To-day at the regular meeting, the question of your future was brought up.'

Mrs. Lippett allowed a moment of silence to fall, then resumed in a slow, placid manner extremely trying to her hearer's suddenly tightened nerves.

`Usually, as you know, the children are not kept after they are sixteen, but an exception was made in your case. You

accustomed to many eyes.

And as each and all of them were warmed without by the sun, so each had a private little sun for her soul to bask in; some dream, some affection, some hobby, at least some remote and distant hope which, though perhaps starving to nothing, still lived on, as hopes will. They were all cheerful, and many of them merry.

They came round by The Pure Drop Inn, and were turning out of the high road to pass through a wicket-gate into the meadows, when one of the women said--

"The Load-a-Lord! Why, Tess Durbeyfield, if there isn't thy father riding hwome in a carriage!"

A young member of the band turned her head at the exclamation. She was a fine and handsome girl--not handsomer than some others, possibly--but her mobile peony mouth and large innocent eyes added eloquence to colour and shape. She wore a red ribbon in her hair, and was the only one of the white company who could boast of such a pronounced adornment. As she looked round Durbeyfield was seen moving alon

THIS book is a slice of intensified historyhistory as I saw it. It does not pretend to be anything but a detailed account of the November Revolution, when the Bolsheviki, at the head of the workers and soldiers, seized the state power of Russia and placed it in the hands of the Soviets.

Naturally most of it deals with Red Petrograd, the capital and heart of the insurrection. But the reader must realize that what took place in Petrograd was almost exactly duplicated, with greater or lesser intensity, at different intervals of time, all over Russia.

In this book, the first of several which I am writing, I must confine myself to a chronicle of those events which I myself observed and experienced, and those supported by reliable evidence; preceded by two chapters briefly outlining the background and causes of the November Revolution. I am aware that these two chapters make difficult reading, but they are essential to an understanding of what follows.

Many questions will suggest themselves to the mind of the reader. What is Bolshevism? What kind of

their respect for the ladies, whom it was their duty to serve. And nearly every other ceremony which has lasted was based on common sense. "Etiquette," as Dr. Brown has said, "with all its littlenesses and niceties, is founded upon a central idea of right and wrong."

The word "courtesy" itself did not come into the language until late (etiquette came even later) and then it was used to describe the polite practices at court. It was wholly divorced from any idea of character, and the most fastidious gentlemen were sometimes the most complete scoundrels. Even the authors of books of etiquette were men of great superficial elegance whose moral standards were scandalously low. One of them, an Italian, was banished from court for having published an indecent poem and wrote his treatise on polite behavior while he was living in enforced retirement in his villa outside the city. It was translated for the edification of the young men of England and France and served as a standard for several generations. Anot