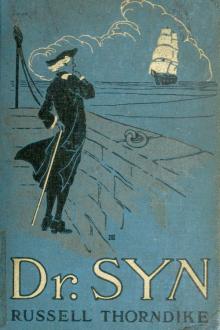

Doctor Syn by Russell Thorndyke (10 best novels of all time .txt) 📖

- Author: Russell Thorndyke

- Performer: -

Book online «Doctor Syn by Russell Thorndyke (10 best novels of all time .txt) 📖». Author Russell Thorndyke

“It was a mistake murdering that revenue man,” agreed Doctor Syn, “but Clegg was drunk, and threw all caution to the devil.”

“Clegg had been drunk enough before,” said the captain, “and yet he had never made a mistake. No, he was too clever to be caught in the meshes of a tavern brawl. Besides, from all we know of his former life, he would surely have put up a better defence at his trial; of course he would. You don’t tell me that a man who could terrorize the high seas all that time was going to let himself swing for a vulgar murder in a Rye tavern.”

“But it is a noticeable thing,” put in the cleric, “that all great criminals have made one stupid blunder that has caused their downfall.”

“Which generally means,” went on the captain, “that up to that moment it was luck and not genius that kept them safe. But we know that Clegg was a genius. I’ve had it first hand from high Admiralty men; from men who have lived in the colonies and traded in Clegg’s seas. The more I hear about that rascally pirate the more it makes me wonder; and some day I mean to give the time to clearing up the mystery.”

“What mystery?” said the cleric.

“The mystery of how Clegg could persuade another man to commit wilful murder in order to take his name upon the scaffold,” said the captain. “It takes some powers of persuasion to accomplish that, you’ll agree.”

“What on earth do you mean?” said the cleric.

“Simply this,” ejaculated the captain, beating the table with his fist, “that Clegg was never hanged at Rye.”

There was a pause, and the gentlemen looked at him with grave faces. Presently the squire laughed. “Upon my soul, Captain,” he said, “you run our friend Sennacherib here uncommon close with staggering statements. I wonder which of you will tell us first that Queen Anne is not dead.”

“Queen Anne is dead,” exclaimed the captain, “because she was not fortunate enough to persuade somebody else to die for her. Now I maintain that this is exactly what Clegg did do.”

“Can you let us have the reasons that led you to this theory?” said the cleric, interested.

“I don’t see why not,” replied the captain. “In the first place, the man hanged at Rye was a short, thickset man, tattooed from head to foot, wearing enormous brass earrings, and his black hair cropped short as a Roundhead’s.”

“That’s an exact description of him,” said the parson, “for, as everybody knows, I visited the poor wretch in his prison at Rye, and at his desire wrote out his final and horrible confession.”

“Is that so?” said the captain. “Oh, yes, I remember hearing of how he was visited by a parson. I thought it a bit incongruous at the time.”

“And so it was,” agreed the parson, “for I have never seen a more unrepentant man go to meet his Maker.”

“Well, now,” went on the captain, his eyes glistening with excitement, “I have it on very good authority that the real Clegg in no way answered this description: he was a weird -looking fellow; thin faced, thin legs, long arms, and, what’s more to the point, was never tattooed in his life save once by some unskilled artist who had tried to portray a man walking the plank w^ith a shark waiting below. This picture was executed so poorly that the pirate would never let any one try again. Then I also have it on the very best evidence that Clegg’s hair was gray, and had been gray since quite a young man; so that does away with your black, close-cropped hair. And again I have it that Clegg would never permit his ears to be pierced for brass rings, affirming that they were useless lumber for a seaman to carry.”

“Don’t you think,” said the squire, “that all this was a clever dodge to avoid discovery?”

“A disguise?” queried the captain. “Yes, I confess that the same thing occurred to me.”

“And might I ask how you managed to obtain your real description of Clegg .f^” asked the vicar.

“At first,” said the captain, “from second or third sources; but the other day I got first-hand evidence from a man who had served aboard Clegg’s ship, the Imogene. That ugly-looking rascal who was helping Bill Spiker carry the rum-barrel. The bo’sun questioned him for upward of three hours in his queer lingo, and managed to arrive, by the nodding and shaking of the man’s head, at an exact description of him tallying with mine and yours” (glancing at Doctor Syn).

“He was one of Clegg’s men?” said the vicar, amazed. “Then pray, sir, what is he doing in the royal navy?”

“I use him as tracker,” replied the captain. “You know, some of these half-caste mongrels, mixtures of all the bad blood in the Southern Seas, have remarkable gifts of tracking. It’s positively uncanny the way this rascal can smell out a trapdoor or a hidingplace. He’s invaluable to me on these smuggling trips. I suppose you’ve nothing of the sort in this house?”

“There’s a staircase leading to a priest’s hole in this very chimney corner, though you would never guess at it,” returned the squire. “And, what’s more, I bet a guinea that nobody would discover it.”

“I’ll lay you ten to one that the mulatto will; aye, and within a quarter of an hour!”

“Done!” cried the squire. “This will be sport; we’ll have him round,” and he summoned the butler.

“There’s one condition I should have made,” said the captain when the butler opened the door. “The rascal is dumb and cannot speak a word of English; but my bo’sun can speak his lingo and will make him understand what we require of him.”

“Fetch ‘em both round,” cried the squire. “Gadzooks! it’s a new sport this.”

The butler was accordingly dispatched with the captain’s orders to the bo’sun that he should step round at once to the Court House with the mulatto. Meantime, Denis was summoned from the paths of learning, and the terms of the wager having been explained to him, he awaited in high excitement the coming of the seamen.

“How is it that the fellow’s dumb?” asked the physician.

“Tongue cut out at the roots, sir,” replied the captain. “He might well be deaf, too, for his ears are also gone, probably along with his tongue, but he’s not deaf, he understands the bo’sun all right.”

“Did you ever find out how he lost them?” asked the squire.

“It was Clegg,” replied the captain; “for after having been tortured in this pleasant fashion he was marooned upon a coral reef.”

“Good God!” said the vicar, going pale with the thought of it.

“How did he get off?” asked the squire.

“God alone knows,” returned the captain.

“Can’t you get it out of him in some way?” said the squire.

“Job Mallet, the bo’sun, can’t make him understand some things,” said the captain, “but he located the reef upon which he’d been marooned in the Admiralty chart, and it’s as Godforsaken a piece of rock as you could wish. No vegetation; far from the beat of ships; not even registered upon the mercantile maps. As well be the man in the moon as a man on that reef for all the chance you’d have to get off.”

“But he got off,” said the squire. “How?”

“That’s just it,” said the captain, “how? If you can find that out you’re smarter than Job Mallet, who seems the only man who can get things out of him.”

“By Gad! I’m quite eager to look at the poor devil!” cried the squire.

“So am I,” agreed the physician.

“And I’d give a lot to know how he got off that reef,” said Doctor Syn.

But at that instant the butler opened the door, and Job Mallet shuffled into the room, looking troubled.

“Where’s the mulatto?” said the captain sharply, for the bo’sun was alone.

“I don’t know, sir,” answered the bo’sun sheepishly; “he’s gone!”

“Gone? Where to?” said the captain.

“Don’t know, sir,” answered the bo’sun. “I see him curled up in the barn along of the others just afore I stepped outside to stand watch, and when I went to wake him to bring him along of me, why, blest if he hadn’t disappeared.”

“Did you look for him?” said the captain.

“Well, sir, I was a-lookin’ for him as far down as to the end of the field where one of them ditches run,” said the bo’sun, “when I see something wot fair beat anything I ever seed afore: it was a regiment of horse, some twenty of ‘em maybe, but if them riders weren’t devils, well, I ain’t a seaman.”

“What were they like?” screamed Sennacherib.

“Wild-looking fellows on horses wot seemed to snort out fire, and the faces of the riders and horses were all moonlight sort of colour, but before I’d shouted, ‘Belay there!’ they’d all disappeared in the mist.”

“How far away were these riders?” said the captain.

“Why, right on top of me, as it seemed,” stammered the bo’sun.

“Job Mallet,” said the captain, shaking his large finger at him, “I’ll tell you what it is, my man: you’ve been drinking rum.”

“Well, sir,” admitted the seaman, “it did seem extra good tonight, and perhaps I did take more than I could manage; though come to think of it, sir, I’ve often drunk more than I’ve swallowed tonight and not seen a thing, sir.”

“You get back to the barn and go to sleep,” said the captain, “and lock the door from the inside; there’s no need to stand watches tonight, and it won’t do that foreign rascal any harm to find himself on the wrong side of the door for once.” Job Mallet saluted and left the room.

“You see what it comes to, Sennacherib,” laughed the squire: “drink too much and you’re bound to see devils!”

“I don’t believe that fellow has drunk too much,” said the physician, getting up. “But I’m walking home, and it’s late; time I made a start.”

“Mind the devils!” laughed the vicar as he shook hands.

“They’ll mind me, sir,” said Sennacherib as he grasped his thick stick. And so the supper party broke up: the squire lighting the captain to his room; Doctor Syn returning to the vicarage; and Sennacherib Pepper setting out for his lonely walk across the devil-ridden Marsh.

The window of the captain’s room looked out upon the courtyard; he could see nothing of the sea, nothing of the Marsh. Now, as these were the two things he intended to see—aye, and on that very night—he waited patiently till the house was still; for he considered that there was more truth in Sennacherib Pepper’s stories than the squire allowed. Indeed, it was more than likely that the squire disallowed them for reasons of his own. This he determined to find out. So half an hour after the squire had bade him goodnight he softly crossed the room to open the door.

But the door was locked on the outside!

NOW Jerry lived with his grandparents, and they were always early to bed. Indeed, by ten o’clock they were both snoring loudly, while Jerry would be tucked up in the little attic dreaming of the gallows and hanging Mr. Rash. Jerry was troubled a good deal by dreams; but upon this particular night they were more than usually violent; whether owing to the great excitement caused by the coming of the King’s men, or due to the extra doses of rum that the youngster had indulged in, who can say. He dreamt that he was out on the Marsh chasing the schoolmaster: that was all very well, quite

Comments (0)