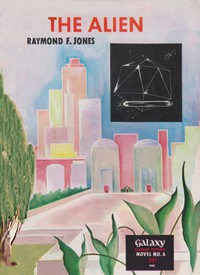

The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖». Author Raymond F. Jones

The exposed half was a shining thing of ebony, whose planes and angles were machined with mathematical exactness. It looked as if there were at least a thousand individual facets on the one hemisphere alone.

At the sight of it, Underwood could almost understand the thrill of discovery that impelled these archeologists to delve in the mysteries of space for lost kingdoms and races. This object which Terry had discovered was a magnificent artifact. He wondered how long it had circled the Sun since the intelligence that formed it had died. He wished now that Terry had not used the Atom Stream, for that had probably destroyed the validity of the radium-lead relationship in the coating of debris that might otherwise indicate something of the age of the thing.

Terry sensed something of Underwood's awe in his silence as he approached. "What do you think of it, Del?"

"It's—beautiful," said Underwood. "Have you any clue to what it is?"

"Not a thing. No marks of any kind on it."

The scooter slowed as Del Underwood guided it near the surface of the asteroid. It touched gently and he unstrapped himself and stepped off. "Phyfe will forgive all your sins for this," he said. "Before you show me the Atom Stream is ineffective, let's break off a couple of tons of the coating and put it in the ship. We may be able to date the thing yet. Almost all these asteroids have a small amount of radioactivity somewhere in them. We can chip some from the opposite side where the Atom Stream would affect it least."

"Good idea," Terry agreed. "I should have thought of that, but when I first found the single outcropping of machined metal, I figured it was very small. After I found the Atom Stream wouldn't touch it, I was overanxious to undercover it. I didn't realize I'd have to burn away the whole surface of the asteroid."

"We may as well finish the job and get it completely uncovered. I'll have some of my men from the ship come on over."

It took the better part of an hour to chip and drill away samples to be used in a dating attempt. Then the intense fire of the Atom Stream was turned upon the remainder of the asteroid to clear it.

"We'd better be on the lookout for a soft spot." Terry suggested. "It's possible this thing isn't homogeneous, and Papa Phyfe would be very mad if we burned it up after making such a find."

From behind his heavy shield which protected him from the stray radiation formed by the Atom Stream, Delmar Underwood watched the biting fire cut between the gemlike artifact and the metallic alloys that coated it. The alloys cracked and fell away in large chunks, propelled by the explosions of matter as the intense heat vaporized the metal almost instantly.

The spell of the ancient and the unknown fell upon him and swept him up in the old mysteries and the unknown tongues. Trained in the precise methods of the physical sciences, he had long fought against the fascination of the immense puzzles which the archeologists were trying to solve, but no man could long escape. In the quiet, starlit blackness there rang the ancient memories of a planet vibrant with life, a planet of strange tongues and unknown songs—a planet that had died so violently that space was yet strewn with its remains—so violently that somewhere the echo of its death explosion must yet ring in the far vaults of space.

Underwood had always thought of archeologists as befogged antiquarians poking among ancient graves and rubbish heaps, but now he knew them for what they were—poets in search of mysteries. The Bible-quoting of Phyfe and the swearing of red-headed Terry Bernard were merely thin disguises for their poetic romanticism.

Underwood watched the white fire of the Atom Stream through the lead glass of the eye-protecting lenses. "I talked to Illia today," he said. "She says I've run away."

"Haven't you?" Terry asked.

"I wouldn't call it that."

"It doesn't make much difference what you call it. I once lived in an apartment underneath a French horn player who practised eight hours a day. I ran away. If the whole mess back on Earth is like a bunch of horn blowers tootling above your apartment, I say move, and why make any fuss about it? I'd probably join the boys on Venus myself if my job didn't keep me out here. Of course it's different with you. There's Illia to be convinced—along with your own conscience."

"She quotes Dreyer. He's one of your ideals, isn't he?"

"No better semanticist ever lived," Terry said flatly. "He takes the long view, which is that everything will come out in the wash. I agree with him, so why worry—knowing that the variants will iron themselves out, and nothing I can possibly do will be noticed or missed? Hence, I seldom worry about my obligations to mankind, as long as I stay reasonably law-abiding. Do likewise, Brother Del, and you'll live longer, or at least more happily."

Underwood grinned in the blinding glare of the Atom Stream. He wished life were as simple as Terry would have him believe. Maybe it would be, he thought—if it weren't for Illia.

As he moved his shield slowly forward behind the crumbling debris, Underwood's mind returned to the question of who created the structure beneath their feet, and to what alien purpose. Its black, impenetrable surfaces spoke of excellent mechanical skill, and a high science that could create a material refractory to the Atom Stream. Who, a half million years ago, could have created it?

The ancient pseudo-scientific Bode's Law had indicated a missing planet which could easily have fitted into the Solar System in the vicinity of the asteroid belt. But Bode's Law had never been accepted by astronomers—until interstellar archeology discovered the artifacts of a civilization on many of the asteroids.

The monumental task of exploration had been undertaken more than a generation ago by the Smithson Institute. Though always handicapped by shortage of funds, they had managed to keep at least one ship in the field as a permanent expedition.

Dr. Phyfe, leader of the present group, was probably the greatest student of asteroidal archeology in the System. The younger archeologists labeled him benevolently Papa Phyfe, in spite of the irascible temper which came, perhaps, from constantly switching his mind from half a million years ago to the present.

In their use of semantic correlations, Underwood was discovering, the archeologists were far ahead of the physical scientists, for they had an immensely greater task in deducing the mental concepts of alien races from a few scraps of machinery and art.

Of all the archeologists he had met, Underwood had taken the greatest liking to Terry Bernard. An extremely competent semanticist and archeologist, Terry nevertheless did not take himself too seriously. He did not even mind Underwood's constant assertion that archeology was no science. He maintained that it was fun, and that was all that was necessary.

At last, the two groups approached each other from opposite sides of the asteroid and joined forces in shearing off the last of the debris. As they shut off the fearful Atom Streams, the scientists turned to look back at the thing they had cleared.

Terry said quietly, "See why I'm an archeologist?"

"I think I do—almost," Underwood answered.

The gemlike structure beneath their feet glistened like polished ebony. It caught the distant stars in its thousand facets and cast them until it gleamed as if with infinite lights of its own.

The workmen, too, were caught in its spell, for they stood silently contemplating the mystery of a people who had created such beauty.

The spell was broken at last by a movement across the heavens. Underwood glanced up. "Papa Phyfe's coming on the warpath. I'll bet he's ready to trim my ears for taking the lab ship without his consent."

"You're boss of the lab ship, aren't you?" said Terry.

"It's a rather flexible arrangement—in Phyfe's mind, at least. I'm boss until he decides he wants to do something."

The headquarters ship slowed to a halt and the lock opened, emitting the fiery burst of a motor scooter which Doc Phyfe rode with angry abandon.

"You, Underwood!" His voice came harshly through the phones. "I demand an explanation of—"

That was as far as he got, for he glimpsed the thing upon which the men were standing, and from his vantage point it looked all the more like a black jewel in the sky. He became instantly once more the eager archeologist instead of expedition administrator, a role he filled with irritation.

"What have you got there?" he whispered.

Terry answered. "We don't know. I asked Dr. Underwood's assistance in uncovering the artifact. If it caused you any difficulty, I'm sorry; it's my fault."

"Pah!" said Phyfe. "A thing like this is of utmost importance. You should have notified me immediately."

Terry and Underwood grinned at each other. Phyfe reprimanded every archeologist on the expedition for not notifying him immediately whenever anything from the smallest machined fragment of metal to the greatest stone monuments were found. If they had obeyed, he would have done nothing but travel from asteroid to asteroid over hundreds of thousands of miles of space.

"You were busy with your own work," said Terry.

But Phyfe had landed, and as he dismounted from the scooter, he stood in awe. Terry, standing close to him, thought he saw tears in the old man's eyes through the helmet of the spaceship.

"It's beautiful!" murmured Phyfe in worshipping awe. "Wonderful. The most magnificent find in a century of asteroidal archeology. We must make arrangements for its transfer to Earth at once."

"If I may make a suggestion," said Terry, "you recall that some of the artifacts have not survived so well. Decay in many instances has set in—"

"Are you trying to tell me that this thing can decay?" Phyfe's little gray Van Dyke trembled violently.

"I'm thinking of the thermal transfer. Doctor Underwood is better able to discuss that, but I should think that a mass of this kind, which is at absolute zero, might undergo unusual stresses in coming to Earth normal temperatures. True, we used the Atom Stream on it, but that heat did not penetrate enough to set up great internal stresses."

Phyfe looked hesitant and turned to Underwood. "What is your opinion?"

Underwood didn't get it until he caught Terry's wink behind Phyfe's back. Once it left space and went into the museum laboratory, Terry might never get to work on the thing again. That was the perpetual gripe of the field men.

"I think Doctor Bernard has a good point," said Underwood. "I would advise leaving the artifact here in space until a thorough examination has been made. After all, we have every facility aboard the Lavoisier that is available on Earth."

"Very well," said Phyfe. "You may proceed in charge of the physical examination of the find, Doctor Underwood. You, Doctor Bernard, will be in charge of proceedings from an archeological standpoint. Will that be satisfactory to everyone concerned?"

It was far more than Terry had expected.

"I will be on constant call," said Phyfe. "Let me know immediately of any developments." Then the uncertain mask of the executive fell away from the face of the little old scientist and he regarded the find with humility and awe. "It's beautiful," he murmured again, "beautiful."

CHAPTER TWOPhyfe remained near the site as Underwood and Terry set their crew to the routine task of weighing, measuring, and photographing the object, while Underwood considered what else to do.

"You know, this thing has got me stymied, Terry. Since it can't be touched by an Atom Stream, that means there isn't a single analytical procedure to which it will respond—that I know of, anyway. Does your knowledge of the Stroids and their ways of doing things suggest any identification of it?"

Terry shook his head as he stood by the port of the laboratory ship watching the crews at work outside. "Not a thing, but that's no criterion. We know so little about the Stroids that almost everything we find has a function we never heard of before. And of course we've found many objects with totally unknown functions. I've been thinking—what if this should turn out to be merely a natural gem from the interior of the planet, maybe formed at the time of its destruction, but at least an entirely natural object rather than an artifact?"

"It would be the largest crystal formation ever encountered, and the most perfect. I'd say the chances of its natural formation are negligible."

"But maybe this is the one in a hundred billion billion or whatever number chance it may be."

"If so, its value ought to be enough to balance the Terrestrial budget. I'm still convinced that it must be an artifact, though its material and use are beyond me. We can start with a

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)