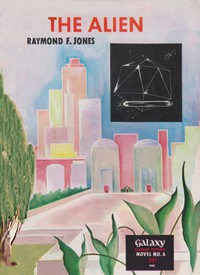

The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖». Author Raymond F. Jones

"Now that we're in here, there is nothing more we can do until we can understand their printed language. Obviously, they must teach it to us. This would be the place."

"You may be right," said Phyfe, "But we archeologists work with facts, not guesses. We'll know soon enough if it's true."

Underwood felt content to speculate while the others worked. There was nothing else for him to do. No way out of the anteroom was apparent, but he was confident that a way to the interior would be found when the inscriptions were deciphered.

He went out to the surface and walked slowly about, peering into the transparent depths with his light. What lay within this repository left by an ancient race that had obviously equaled or surpassed man in scientific attainments? Would it be some vast store of knowledge that would come to bless mankind with greater abundance? Or would it, rather, be a new Pandora's box, which would pour out upon the world new ills to add to its already staggering burden?

The world had about all it could stand now, Underwood reflected. For a century, Earth's scientific production had boomed. Her factories had roared with the throb of incessant production, and the utopia of all the planners of history was gradually coming to pass. Man's capacities for production had steadily increased for five hundred years, and at last the capacities for consumption were rising equally, with correspondingly less time spent in production and greater time spent in consumption.

But the utopia wasn't coming off just as the Utopians had dreamed of it. The ever present curse of enforced leisure was not respecting the new age any more than it had past ages. Men were literally being driven crazy with their super-abundance of luxury.

Only a year before, the so-called Howling Craze had swept cities and nations. It was a wave of hysteria that broke out in epidemic proportions. Thousands of people within a city would be stricken at a time by insensate weeping and despair. One member of a household would be afflicted and quickly it would spread from that man to the family, and from that family it would race the length and breadth of the streets, up and down the city, until one vast cry as of a stricken animal would assault the heavens.

Underwood had seen only one instance of the Howling Craze and he had fled from it as if pursued. It was impossible to describe its effects upon the nervous system—a whole city in the throes of hysteria.

Life was cheap, as were the other luxuries of Earth. Murders by the thousands each month were scarcely noticed, and the possession of weapons for protection had become a mark of the new age, for no man knew when his neighbor might turn upon him.

Governments rose and fell swiftly and became little more than figureheads to carry out the demands of peoples cloyed with the excesses of life. Most significant of all, however, was the inability of any leader to hold any following for more than a short time.

Of all the inhabitants of Earth, there were but a few hundred thousand scientists who were able to keep themselves on even keel, and most of these were now fleeing.

As he thought of these things, Underwood pondered what the opening of the repository of a people who sealed up their secrets half a million years ago would mean to mankind. This must be what Terry felt, he thought.

For perhaps three hours he remained on the outside of the shell, letting his mind idle under the brilliance of the stars. Suddenly, the phones in his helmet came alive with sound. It was the voice of Terry Bernard.

"We've got it, Del," he said quietly. "We can read this stuff like nursery rhymes. Come on down. It tells us how to get into the thing."

Underwood did not hurry. He rose slowly from his sitting position and stared upward at the stars, the same stars that had looked down upon the beings who had sealed up the repository. This is it, he thought. Man can never go back again.

He lowered himself into the opening.

Doctor Phyfe was strangely quiet in spite of their quick success in deciphering the language of the Stroids. Underwood wondered what was going through the old man's mind. Did he, too, sense the magnitude of this moment?

Phyfe said, "They were semanticists as well. They knew Carnovan's frequency. It's right here, the key they used to reveal their language. No one less advanced in semantics than our own civilization could have deciphered it, but with a knowledge of Carnovan's frequency, it is simple."

"Practically hand-picked us for the job," said Terry.

Phyfe's sharp eyes turned upon him suddenly behind the double protection of his spectacles and the transparent helmet of the spacesuit.

"Perhaps," said Phyfe. "Perhaps we are. At any rate, there are certain manipulations to be performed which will open this chamber and provide passage to the interior."

"Where's the door?" said Underwood.

Following the notes he had made, Terry moved about the room, directing Underwood's attention to features of the design. Delicately carved, movable levers formed an intricate combination that suddenly released a section of the floor in the exact center of the room. It depressed slowly, then revolved out of the way.

For a moment no one spoke while Phyfe moved to the opening and peered down. A stairway of the same glistening material as the walls about them led downward into the depths of the repository.

Phyfe stepped down and almost stumbled into the opening. "Watch for those steps," he warned. "They're larger than necessary for human beings."

Giants in those days came to Underwood's mind. He tried to vision the creatures who had walked upon this stairway and touched the hand rail that was shoulder high for him.

The repository was divided into levels and the stairway ended abruptly as they came to the level below the anteroom. The chamber in which they found themselves was crowded with artifacts of strange shapes and varying sizes. Not a thing of familiar cast greeted them. But opposite the bottom of the stairway was a pedestal and upon it rested a booklike object that proved to be hinged metallic sheets, covered with Stroid III inscriptions, when Terry climbed up to examine it. He was unable to move it, but the metal pages were locked with a simple clasp that responded to his touch.

"It looks as if we've got to read our way along," said Terry. "I suppose this will tell us how to get into the next room."

Underwood and the other expedition members moved cautiously about, examining the contents of the room. The two photographers began to make an orderly pictorial record of everything within the chamber.

Standing alone in one corner, Underwood peered at an object that appeared to be nothing but a series of opaque, polychrome globes tangent to each other and mounted on a pedestal.

Whether it were some kind of machine or monument, he could not tell.

"You feel it, too," said a sudden quiet voice behind him. Underwood whirled about in surprise. Phyfe was there behind him, his slight figure a shapeless shadow in the spacesuit.

"Feel what?"

"I've watched you, Doctor Underwood. You are a physicist and in far closer touch with the real world than I. You have seen me—I cannot even manage an expedition with efficiency—my mind lives constantly in the past, and I cannot comprehend the significance of contemporary things. Tell me what it will mean, this intrusion of an alien science into our own."

A sudden, new, and humbling respect filled Underwood. He had never dreamed that the little archeologist had such a penetrating view of himself in his relation to his environment.

"I wish I could answer that question," said Underwood, shaking his head. "I can't. Perhaps if we knew, we'd destroy the thing—or it might be that we'd shout our discovery to the Universe. But we can't know, and we wouldn't dare be the judges if we could. Whatever it is, the ancient Stroids seem to have deliberately attempted to provide for the survival of their culture." He hesitated. "That, of course is my guess."

In the darkened corner of the chamber, Phyfe nodded slowly. "You are right, of course. It is the only answer. We dare not try to be the judges."

Underwood saw that he would get nowhere in his understanding of the Stroid science by merely depending on the translations given him by Terry and Phyfe. He'd have to learn to read the Stroid inscriptions himself. He buttonholed Nichols and got the semanticist to show him the rudiments of the language. It was amazingly simple in principle and constructed along semantic lines.

The going became rapidly heavier, however, and it took them the equivalent of five days to get through the fairly elementary material disclosed in the first level below the antechamber.

The book of metal pages did little to satisfy their curiosity concerning either the ancient planet or its culture. It instructed them further in understanding the language, and addressed them as Unknown friends—the nearest human translation.

As was already apparent, the repository had been prepared to save the highest products of the ancient Stroid culture from the destruction that came upon the world. But the records did not even hint as to the nature of that destruction and they said nothing about the objects in the room.

The scientists were a bit disappointed by the little revealed to them so far, but, as expected, there were instructions to enter the next lower level. There, an entirely different situation confronted them.

The chamber into which they came after winding down a long, spiral stairway, narrow, yet with the same high steps as before, was spherical in shape and seemed to be concentric with the outer shell of the repository. It contained a single object.

The object was a cube in the center of the chamber, about two feet on a side. From the corners of the cube, long supports of complicated spring structure led to the inner surface of the spherical chamber. It appeared to be a highly effective shock mounting for whatever was contained within the cube.

The sight before the men was impressive in simplicity, yet was anticlimactic, for there was nothing here of the great wonders that they had expected. There was only the suspended cube—and a book.

Quickly, Phyfe advanced along the narrow catwalk that led from the opening to the cube. The book lay on a shelf fastened to the side of the cube. Phyfe opened it to the first sheet and read haltingly and laboriously:

"Greetings, Unknown Friends, Greetings to you from the Great One. By the token that you are now reading this, you have proven yourselves mentally capable of understanding the new world of knowledge and discovery that may be yours.

"I am Demarzule, the Great One the greatest of great Sirenia—and the last. And within the storehouse of my mind is the vast knowledge that made Sirenia the greatest world in all the Universe.

"Great as it was, however, destruction came to the world of Sirenia. But her knowledge and her wonders shall never pass. In ages after, new worlds will rise and beings will inhabit them, and they will come to a minimum plane of knowledge that will assure their appreciation of the wonders that may be theirs from the world of Sirenia.

"You have minimum technical knowledge, else you could not have created the radiation necessary to render the storehouse penetrable. You have a minimum semantic knowledge, else you could not have understood my words that have brought you this far.

"You are fit and capable to behold the Great One of Sirenia!"

As Phyfe turned over the first metal sheet, the men looked at each other. It was Nichols, the semanticist, who said, "There are only two possibilities in a mind that would write a statement of that kind. Either it belonged to a truly superior being, or to a maniac. So far, in man's history, there has not been encountered such a superior being. If he existed, it would have been wonderful to have known him."

Phyfe paused and peered with difficulty through the helmet of the spacesuit. He continued, "I live. I am eternal. I am in your midst, Unknown Friends, and to your hands falls the task of bringing speech to my voice, and sight to my eyes, and feeling to my hands. Then, when you have fulfilled your mighty task, you shall behold me and the greatness of the Great One of Sirenia."

Enright, the photographer said, "What the devil does that mean? The guy must have been nuts. He sounds like he expected to come back to life."

The feeling within Underwood was more than bearable.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)